Related Research Articles

The deuterocanonical books, meaning "Of, pertaining to, or constituting a second canon," collectively known as the Deuterocanon (DC), are certain books and passages considered to be canonical books of the Old Testament by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Church, and the Church of the East. In contrast, modern Rabbinic Judaism and Protestants regard the DC as Apocrypha.

The Apocalypse of Peter, also called the Revelation of Peter, is an early Christian text of the 2nd century and a work of apocalyptic literature. It is the earliest-written extant work depicting a Christian account of heaven and hell in detail. The Apocalypse of Peter is influenced by both Jewish apocalyptic literature and Greek philosophy of the Hellenistic period. The text is extant in two diverging versions based on a lost Koine Greek original: a shorter Greek version and a longer Ethiopic version.

The Life of Adam and Eve, also known in its Greek version as the Apocalypse of Moses, is a Jewish apocryphal group of writings. It recounts the lives of Adam and Eve from after their expulsion from the Garden of Eden to their deaths. It provides more detail about the Fall of Man, including Eve's version of the story. Satan explains that he rebelled when God commanded him to bow down to Adam. After Adam dies, he and all his descendants are promised a resurrection.

1 Esdras, also Esdras A, Greek Esdras, Greek Ezra, or 3 Esdras, is the ancient Greek Septuagint version of the biblical Book of Ezra in use within the early church, and among many modern Christians with varying degrees of canonicity. 1 Esdras is substantially similar to the standard Hebrew version of Ezra–Nehemiah, with the passages specific to the career of Nehemiah removed or re-attributed to Ezra, and some additional material.

2 Esdras, also called 4 Esdras, Latin Esdras, or Latin Ezra, is an apocalyptic book in some English versions of the Bible. Tradition ascribes it to Ezra, a scribe and priest of the fifth century BC, whom the book identifies with the sixth-century figure Shealtiel.

The name "Esdras" is found in the title of four texts attributed to, or associated with, the prophet Ezra. The naming convention of the four books of Esdras differs between church traditions, and has changed over time.

The Apocalypse of Paul is a fourth-century non-canonical apocalypse and part of the New Testament apocrypha. The full original Greek version of the Apocalypse of Paul is lost, although fragmentary versions still exist. Using later versions and translations, the text has been reconstructed, notably from Latin and Syriac translations of the work.

The Ascension of Isaiah is a pseudepigraphical Judeo-Christian text. Scholarly estimates regarding the date of the Ascension of Isaiah range from 70 AD to 175 AD. Many scholars believe it to be a compilation of several texts completed by an unknown Christian scribe who claimed to be the Prophet Isaiah, while an increasing number of scholars in recent years have argued that the work is a unity by a single author that may have utilized multiple sources.

2 Baruch is a Jewish apocryphal text thought to have been written in the late 1st century CE or early 2nd century CE, after the destruction of the Temple in CE 70. It is attributed to the biblical figure Baruch ben Neriah and so is associated with the Old Testament, but not regarded as scripture by Jews or by most Christian groups. It is included in some editions of the Peshitta, and is part of the Bible in the Syriac Orthodox tradition. It has 87 sections (chapters).

Written between the 2nd and 5th centuries AD, in Greek, the Apocalypse of Sedrach, also known as the Word of Sedrach, is an ancient apocryphal text. It is preserved only in one 15th century manuscript. The text was published by M. R. James and translated into English by A. Rutherford. Apparently the original apocalypse was composed between AD 150 and 500, it was joined with a lengthy sermon on love to reach its final form shortly after AD 1000. The original was probably Jewish, but this was later edited to take on a Christian flavour.

These are the books of the Vulgate along with the names and numbers given them in the Douay–Rheims and King James versions of the Bible. They are all translations, and the Vulgate exists in many forms. There are 76 books in the Clementine edition of the Latin Vulgate, 46 in the Old Testament, 27 in the New Testament, and 3 in the Apocrypha.

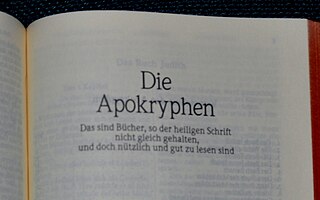

The biblical apocrypha denotes the collection of apocryphal ancient books thought to have been written some time between 200 BC and 100 AD.

The Visio Tnugdali is a 12th-century religious text reporting the otherworldly vision of the Irish knight Tnugdalus. It was "one of the most popular and elaborate texts in the medieval genre of visionary infernal literature" and had been translated from the original Latin forty-three times into fifteen languages by the 15th century, including Icelandic and Belarusian. The work remained most popular in Germany, with ten different translations into German, and four into Dutch. With a recent resurgence of scholarly interest in Purgatory following works by Jacques Le Goff, Stephen Greenblatt and others, the vision has attracted increased academic attention.

The Old Testament is the first section of the two-part Christian biblical canon; the second section is the New Testament. The Old Testament includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) or protocanon, and in various Christian denominations also includes deuterocanonical books. Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Protestants use different canons, which differ with respect to the texts that are included in the Old Testament.

The Questions of Ezra is an ancient Christian apocryphal text, claimed to have been written by the Biblical Ezra. The earliest surviving manuscript, composed in Armenian, dates from 1208 CE. It is an example of the Christian development of topics coming out from the Jewish Apocalyptic literature. Due to the shortness of the book, it is impossible to determine the original language, the provenance or to reliably date it. This text has had no influence outside the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Barontius (Barontus) and Desiderius were two 8th century hermits who are venerated as saints by the Catholic Church. They were hermits near Pistoia, in Italy.

The Codex Sangermanensis I, designated by g1 or 7, is a Latin manuscript, dated AD 822 of portions of the Old Testament and the New Testament. The text, written on vellum, is a version of the Latin. The manuscript contains the Vulgate Bible, on 191 leaves of which, in the New Testament, the Gospel of Matthew contain Old Latin readings. It contains Shepherd of Hermas.

Ezra 4 is the fourth chapter of the Book of Ezra in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible, or the book of Ezra–Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible, which treats the book of Ezra and book of Nehemiah as one book. Jewish tradition states that Ezra is the author of Ezra–Nehemiah as well as the Book of Chronicles, but modern scholars generally accept that a compiler from the 5th century BCE is the final author of these books. The section comprising chapter 1 to 6 describes the history before the arrival of Ezra in the land of Judah in 468 BCE. This chapter records the opposition of the non-Jews to the re-building of the temple and their correspondence with the kings of Persia which brought a stop to the project until the reign of Darius the Great.

The Apocalypse of Pseudo-Ezra is a set of visions of the end times composed in the Syriac language sometime between the 7th and 12th centuries. It is a pseudepigraphon falsely attributed to Ezra. It is a short text of about seven manuscript pages. It recapitulates history in the form of prophecy using obscure animal imagery. Written to console Christians living under Islamic rule, it predicts the end of such rule in the Near East.

The Ethiopic Apocalypse of Ezra, also called the Falasha Apocalypse of Ezra, is an apocalypse written in Geʿez (Ethiopic) that circulated among the Beta Israel (Falasha) and foretold the divine destruction of Islam.

References

- ↑ Gardiner, Eileen (November 11, 1993). Medieval Visions of Heaven and Hell. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315055817-19/vision-ezra-visio-beati-esdrae-eileen-gardiner.

- 1 2 J. R. Mueller and G. A. Robbins, Vision of Ezra (Fourth to Seventh Century A.D.). A New Translation and Introduction, in James H. Charlesworth (1985), The Old Testament Pseudoepigrapha, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company Inc., Volume 2, ISBN 0-385-09630-5 (Vol. 1), ISBN 0-385-18813-7 (Vol. 2). Here cited vol. 1 p. 582.