Helmond is a city and municipality in the Metropoolregio Eindhoven of the province of North Brabant in the Southern Netherlands.

Batik is an Indonesian technique of wax-resist dyeing applied to the whole cloth. This technique originated from the island of Java, Indonesia. Batik is made either by drawing dots and lines of wax with a spouted tool called a canting, or by printing the wax with a copper stamp called a cap. The applied wax resists dyes and therefore allows the artisan to colour selectively by soaking the cloth in one colour, removing the wax with boiling water, and repeating if multiple colours are desired.

Kente refers to a Ghanaian textile made of hand-woven strips of silk and cotton. Historically the fabric was worn in a toga-like fashion by royalty among the Ashanti and Akan. According to Ashanti oral tradition, it originated from Bonwire in the Ashanti region of Ghana. In modern day Ghana, the wearing of kente cloth has become widespread to commemorate special occasions, and kente brands led by master weavers are in high demand. Kente is also worn in parts of Togo and Ivory Coast by the Ewe and Akan people there.

Yinka Shonibare, is a British artist living in the United Kingdom. His work explores cultural identity, colonialism and post-colonialism within the contemporary context of globalisation. A hallmark of his art is the brightly coloured Ankara fabric he uses. As Shonibare is paralysed on one side of his body, he uses assistants to make works under his direction.

The dashiki is a colorful garment that covers the top half of the body, worn mostly in West Africa. It has formal and informal versions and varies from simple draped clothing to fully tailored suits. A common form is a loose-fitting pullover garment, with an ornate V-shaped collar, and tailored and embroidered neck and sleeve lines. It is frequently worn with a brimless kufi cap and pants. It has been popularized and claimed by communities in the African diaspora, especially African Americans.

The wrapper, lappa, or pagne is a colorful garment widely worn in West Africa by both men and women. It has formal and informal versions and varies from simple draped clothing to fully tailored ensembles. The formality of the wrapper depends on the fabric used to create or design it.

A kitenge or chitenge is an East African, West African and Central African piece of fabric similar to a sarong, often worn by women and wrapped around the chest or waist, over the head as a headscarf, or as a baby sling. Kitenges are made of colorful fabric that contains a variety of patterns and designs. In coastal areas of Kenya and in Tanzania, kitenges often have Swahili sayings written on them. There seems to be a confusion with the Kangas, which indeed carry texts in contrast with kitenges, which apparently typically do not carry texts.

John Arthur Fentener van Vlissingen is a Dutch businessman. He is one of the wealthiest people in the Netherlands and has made major investments in the travel industry. The total capital of the family is, according to Quote magazine, around 9.2 billion euros. The wealth of Fentener van Vlissingen was calculated to be €1.6 billion in Quote 500.

The Compagnie Béninoise de Négoce et de Distribution, known as CBND, is a retail and trading company based in Benin.

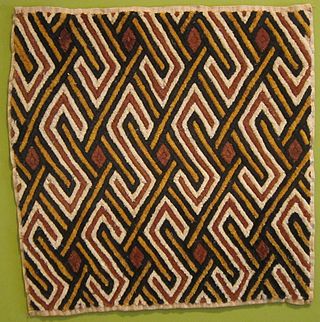

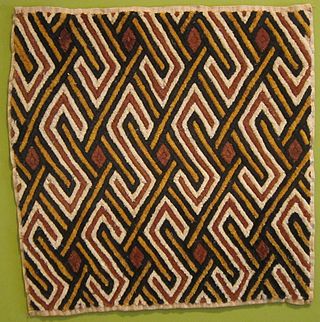

African textiles are textiles from various locations across the African continent. Across Africa, there are many distinctive styles, techniques, dyeing methods, and decorative and functional purposes. These textiles hold cultural significance and also have significance as historical documents of African design.

Resist dyeing (resist-dyeing) is a traditional method of dyeing textiles with patterns. Methods are used to "resist" or prevent the dye from reaching all the cloth, thereby creating a pattern and ground. The most common forms use wax, some type of paste made from starch or mud, or a mechanical resist that manipulates the cloth such as tying or stitching. Another form of resist involves using a dye containing a chemical agent that will repel another type of dye printed over the top. The best-known varieties today include tie-dye, batik, and ikat.

Obin, real name Josephine Komara, is a textile designer from Indonesia. She is sometimes called a "national treasure" due to her passion for and promotion of traditional Indonesian batik techniques. Her work has achieved worldwide recognition, with fellow Indonesian designers such as Edward Hutabarat and Ghea Panggabean describing her as the real authority and leader of the mid-2000s movement to update and modernise batik. Despite this, Obin describes herself as simply a tukang kain, or vendor of cloth, stating that the genuine artists and designers are the craftsmen who make the textiles retailed through Bin House, her business.

Printex Limited is a privately owned textile manufacturing company headquartered in Accra, the capital of Ghana, with over 500 employees. The company was established in 1958 as Millet Textile Corporation (MTC), producing mainly terry towels. Printex prints are a combination of art, cultural inspirations, and interpretations of Africa’s landscape, and wildlife.

African wax prints, Dutch wax prints or Ankara, are a type of common material for clothing in West Africa and Central Africa. They were introduced to West and Central Africans by Dutch merchants during the 19th century, who took inspiration from native Indonesian designs. They began to adapt their designs and colours to suit the tastes of the African market. They are industrially produced colourful cotton cloths with batik-inspired printing. One feature of these materials is the lack of difference in the colour intensity of the front and back sides. The wax fabric can be sorted into categories of quality due to the processes of manufacturing. The term "Ankara" originates from the Hausa name for Accra, the capital of what is now Ghana. Initially used by Nigerian Hausa tradesmen, it was meant to refer to "Accra," which served as a hub for African prints in the 19th century.

Shweshwe is a printed dyed cotton fabric widely used for traditional Southern African clothing. Originally dyed indigo, the fabric is manufactured in a variety of colours and printing designs characterised by intricate geometric patterns. Due to its popularity, shweshwe has been described as the denim, or tartan, of South Africa.

Amarachi Nwosu is a Nigerian-American photographer, visual artist, filmmaker, writer and speaker currently based in New York City. She is also the founder of Melanin Unscripted, a creative platform and agency aimed to dismantle stereotypes and blur cultural lines by exposing complex identities and cultures around the world. Her debut documentary "Black in Tokyo" premiered at the International Center of Photography at the ICP Museum, New York City in 2017 and she has also screened the film in Tokyo, Japan at Ultra Super New Gallery in Harajuku.

Akosombo Textile Limited (ATL) is a textile company in Ghana that produces real wax and African Fancy prints with 100% cotton. It is located on the grounds next to the Akosombo Dam in the Eastern Region. It has weaving, spinning and finishing facilities. It has four fabric labels: ATL, ABC, Treasure and Inspiration. The company's current manager is Ing. Kenneth Asare

Ahwenepa nkasa is the Ghanaian given name for a fabric print found in Ghana, Togo, Benin and the Ivory Coast. This fabric is produced by Ghana Textiles Company (GTP) under VLISCO and Akosombo Industrial Company Limited, formerly called Akosombo Textile Limited (ATL). This fabric design is considered a classic design in West Africa just as other designs like L’Oeil de Boeuf and Sika wo ntaban.

Sika Wɔ Ntaban is the Ghanaian given name for a fabric print found in Ghana, Togo and Nigeria. This fabric is produced by Ghana Textiles Company(GTP) under VLISCO and Akosombo Industrial Company Limited formerly called Akosombo Textiles Limited(ATL).

L’Oeil de Boeuf is the given name for a fabric design found in West African fabric markets produced by VLISCO. This fabric design is considered a classic design in West Africa just as other designs like Ahwenepa Nkasa and Sika wo ntaban.