The 1320s was a decade of the Julian Calendar which began on January 1, 1320, and ended on December 31, 1329.

Year 1323 (MCCCXXIII) was a common year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1324 (MCCCXXIV) was a leap year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1325 (MCCCXXV) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

The Capetian house of Valois was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. They succeeded the House of Capet to the French throne, and were the royal house of France from 1328 to 1589. Junior members of the family founded cadet branches in Orléans, Anjou, Burgundy, and Alençon.

Philip VI, called the Fortunate or the Catholic and of Valois, was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 1328 until his death in 1350. Philip's reign was dominated by the consequences of a succession dispute. When King Charles IV of France died in 1328, his nearest male relative was his nephew, King Edward III of England, but the French nobility preferred Charles's paternal cousin, Philip.

Charles IV, called the Fair in France and the Bald in Navarre, was last king of the direct line of the House of Capet, King of France and King of Navarre from 1322 to 1328. Charles was the third son of Philip IV; like his father, he was known as "the fair" or "the handsome".

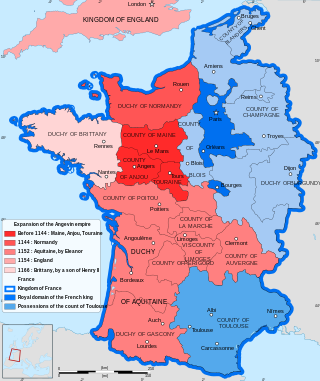

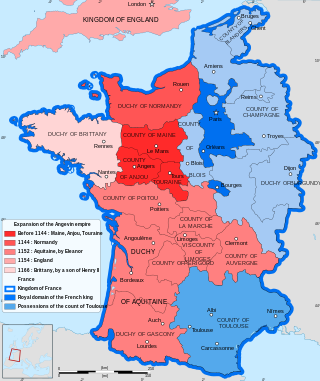

The Duke of Aquitaine was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent, whose seat was Arundel Castle in Sussex, was the sixth son of King Edward I of England, and the second by his second wife Margaret of France, and was a younger half-brother of King Edward II. Edward I had intended to make substantial grants of land to Edmund, but when the king died in 1307, Edward II refused to respect his father's intentions, mainly due to his favouritism towards Piers Gaveston. Edmund remained loyal to his brother, and in 1321 he was created Earl of Kent. He played an important part in Edward's administration as diplomat and military commander and in 1321–22 helped suppress a rebellion.

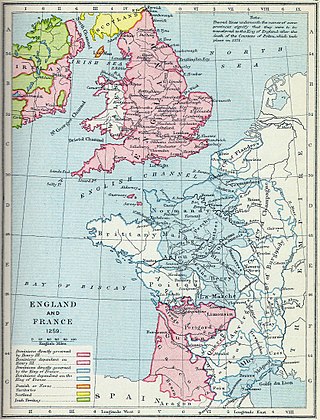

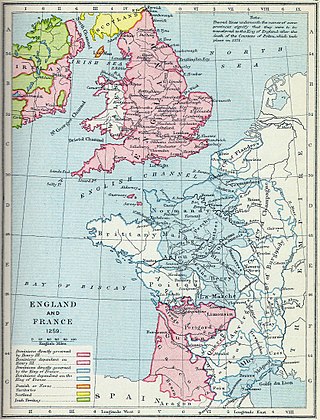

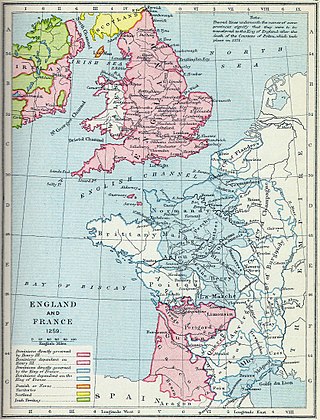

This is a timeline of the Hundred Years' War between England and France from 1337 to 1453 as well as some of the events leading up to the war.

Sir Oliver Ingham was an English knight and landowner who served as a soldier and administrator under King Edward II of England and his successor, King Edward III. He was responsible for the civil government and military defence of the Duchy of Aquitaine during the War of Saint-Sardos and the early part of the Hundred Years' War.

The 1303 Treaty of Paris was a peace treaty between King Edward I of England and Philip IV of France that ended the 1294–1303 Anglo-French War. It was signed at Paris on 20 May 1303 and maintained peace between the two realms until the 1324 War of Saint-Sardos.

Amanieu VII was the Lord of Albret from 1298 until his death; the son of Amanieu VI.

Events from the 1320s in England.

The Hundred Years' War was a series of armed conflicts fought between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from English claims to the French throne initially made by Edward III of England. The war grew into a broader military, economic, and political struggle involving factions from across Western Europe, fueled by emerging nationalism on both sides. The periodization of the war typically charts it as taking place over 116 years. However, it was an intermittent conflict which was frequently interrupted by external factors, such as the Black Death, and several years of truces.

The 1294–1303 Anglo-French War or Guyenne War was a conflict between the kingdoms of France and England, which held many of its territories in nominal homage to France. It began with personal clashes between sailors in the English Channel in the early 1290s but became a widespread conflict over control of Edward I's Continental holdings after he refused a summons from Philip IV and renounced his state of vassalage. Most of the fighting occurred in the Duchy of Aquitaine, made up of the areas of Guyenne and Gascony. The first phase of the war lasted from 1294 to 1298, by which time Flanders had risen in revolt against France and Scotland against England. Hostilities concluded for a time under papal mediation, with the terms of the 1299 Treaty of Montreuil providing for the betrothal of Edward's son Prince Edward and Philip's daughter Isabella. The same year, Edward I also married Philip IV's sister Margaret. The second phase ran from 1300–03, until it was concluded by the 20 May 1303 Treaty of Paris, which reaffirmed the prince and princess's engagement. They were married in 1308.

The Gascon campaign of 1294 to 1303 was a military conflict between English and French forces over the Duchy of Aquitaine, including the Duchy of Gascony. The Duchy of Aquitaine was held in fief by King Edward I of England as a vassal of King Philip IV of France. Starting with a fishing fleet dispute and then naval warfare, the conflict escalated to open warfare between the two countries. In spite of a French military victory on the ground, the war ended when the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1303, which restored the status quo. The war was a premise to future tensions between the two nations culminating in the Hundred Years' War.

Ralph Basset, 2nd Baron Basset of Drayton was a 13th-14th century English nobleman who fought in both the Anglo-French War and in the First War of Scottish Independence.

Robert VIII Bertrand de Bricquebec, also known as Robert Bertrand, Baron of Bricquebec, Viscount of Roncheville, was a 14th century Norman noble. He served as Marshal of France from 1325 until 1344.