This article needs additional citations for verification .(February 2013) |

Whitefriars is an area in the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London. Until 1540, it was the site of a Carmelite monastery, from which it gets its name.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(February 2013) |

Whitefriars is an area in the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London. Until 1540, it was the site of a Carmelite monastery, from which it gets its name.

The area takes its name from the medieval Carmelite religious house, known as the White Friars, that lay here between about 1247 and 1538. [1] [2] Only a crypt remains today of what was once a late 14th century priory belonging to a Carmelite order popularly known as the White Friars because of the white mantles they wore on formal occasions. [2] During its heyday, the priory sprawled the area from Fleet Street to the Thames. At its western end was the Temple and to its east was Water Lane (now called Whitefriars Street). A church, cloisters, garden and cemetery were housed in the ground.

The roots of the Carmelite order go back to its founding on Mount Carmel, which was situated in what is today Israel, in 1150. The order had to flee Mount Carmel to escape the wrath of the Saracens in 1238. Some members of the order found a sympathizer in Richard, Earl of Cornwall, and brother of King Henry III, who helped them travel to England, where they built a church on Fleet Street in 1253. A larger church supplanted this one a hundred years later.

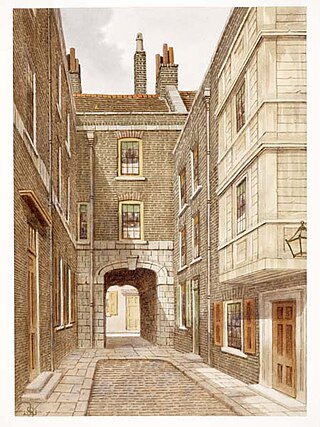

A vaulted cellar of the medieval friary survives under the modern 65 Fleet Street building. The 14th-century cellar was probably part of the White Friars prior's mansion. The medieval remains were lifted up on a crane during the construction of the modern building in 1991 and then replaced (in a slightly altered location); the cellar or 'crypt' can be viewed from Magpie Alley to the south of Fleet Street. [3]

Whitefriars was known as a red-light district in early modern England; and (under the name of Alsatia) as a haunt of criminals, [4] being a place of sanctuary until 1697.

Alsatia was the name given to an area within Whitefriars that was once privileged as a sanctuary. It spanned from the Whitefriars monastery to the south of the west end of Fleet Street and adjacent to the Temple. Between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries it was proofed against all but a writ of the Lord Chief Justice or of the Lords of the Privy Council, [5] becoming a refuge for perpetrators of every grade of crime.

It was named after the ancient name for Alsace, a region outside legislative and juridical lines,[ citation needed ] and first appeared in print in a 1688 play by Thomas Shadwell, The Squire of Alsatia . To this day it remains used as a term depicting an area beyond the law. [6]

The execution of a warrant in Alsatia, if at any time practicable, was attended with great danger, as all united in a maintenance in common of the immunity of the place. It was one of the last places of sanctuary used in England, abolished by Act of Parliament named The Escape from Prison Act in 1697. [5] Aside from whitefriars, eleven other places in London were named in the Act: The Minories, The Mint, Salisbury Court, Fulwoods Rents, Mitre Court, Baldwins Gardens, The Savoy, The Clink, Deadmans Place, Montague Close, and Ram Alley. [5] Further acts in the 1720s abolished sanctuary in The Mint and Stepney.

In the reign of Edward I., a certain Sir Robert Gray, moved by qualms of conscience or honest impulse, founded on the bank of the Thames, east of the well-guarded Temple, a Carmelite convent, with broad gardens, where the white friars might stroll, and with shady nooks where they might con their missals. Bouverie Street and Ram Alley were then part of their domain, and there they watched the river and prayed for their patrons' souls. In 1350 Courtenay, Earl of Devon, rebuilt the Whitefriars Church, and in 1420 a Bishop of Hereford added a steeple. In time, greedy hands were laid roughly on cope and chalice, and Henry VIII., seizing on the friars' domains, gave his physician—that Doctor Butts mentioned by Shakespeare—the chapter-house for a residence. Edward VI.—who, with all his promise, was as ready for such pillage as his tyrannical father—pulled down the church, and built noblemen's houses in its stead. The refectory of the convent, being preserved, afterwards became the Whitefriars Theatre. The mischievous right of sanctuary was preserved to the district, and confirmed by James I., in whose reign the slum became jocosely known as Alsatia— from Alsace, that unhappy frontier then, and later, contended for by French and Germans—just as Chandos Street and that shy neighbourhood at the north-west side of the Strand used to be called the Caribbee Islands, from its countless straits and intricate thieves' passages. The outskirts of the Carmelite monastery had no doubt become disreputable at an early time, for even in Edward III.'s reign the holy friars had complained of the gross temptations of Lombard Street (an alley near Bouverie Street). Sirens and Dulcineas of all descriptions were ever apt to gather round monasteries. Whitefriars, however, even as late as Cromwell's reign, preserved a certain respectability; for here, with his supposed wife, the Dowager Countess of Kent, Selden lived and studied.

— According to Walter Thornbury, in his 1878 book Old and New London [7]

Blackfriars is in central London, specifically the south-west corner of the City of London.

White friars are members of the Order of Carmelites.

The Whitefriars Theatre was a theatre in Jacobean London, in existence from 1608 to the 1620s — about which only limited and sometimes contradictory information survives.

The Dutch Church, Austin Friars, is a reformed church in the Broad Street Ward, in the City of London. Located on the site of the 13th-century Augustinian friary, the original building granted to Protestant refugees for their church services in 1550 was destroyed during the London Blitz.

St Ann Blackfriars was a church in the City of London, in what is now Ireland Yard in the ward of Farringdon Within. The church began as a medieval parish chapel, dedicated to St Ann, within the church of the Dominicans. The new parish church was established in the 16th century to serve the inhabitants of the precincts of the former Dominican monastery, following its dissolution under King Henry VIII. It was near the Blackfriars Theatre, a fact which displeased its congregation. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666.

Ipswich Whitefriars was the medieval religious house of Carmelite friars which formerly stood near the centre of the town of Ipswich, the county town of Suffolk, UK. It was the last of the three principal friaries to be founded in Ipswich, the first being the Ipswich Greyfriars (Franciscans), under Tibetot family patronage before 1236, and the second the Ipswich Blackfriars (Dominicans) founded by King Henry III in 1263. The house of the Carmelite Order of White Friars was established in c. 1278–79. In its heyday it was the home of many eminent scholars, supplied several Provincial superiors of the Order in England, and was repeatedly host to the provincial chapters of the Order.

Our Lady of Doncaster is a Marian shrine located in Doncaster, South Yorkshire, England. The original statue in the Carmelite friary was destroyed during the English Reformation. A modern shrine was erected in St Peter-in-Chains Church, Doncaster in 1973. The feast day of Our Lady of Doncaster is 4 June.

Whitefriars was a Carmelite friary on the lower slopes of St Michael's Hill, Bristol, England. It was established in 1267; in subsequent centuries a friary church was built and extensive gardens developed. The establishment was dissolved in 1538.

Whitefriars, also known as the White Friars or The College of Carmelites, Gloucester, England, was a Carmelite friary of which nothing now survives.

Greyfriars, Stamford was a Franciscan friary in Stamford, Lincolnshire, England. It was one of many religious houses suppressed and closed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century. The site is now part of the NHS Stamford and Rutland Hospital.

Boston Friary refers to any one of four friaries that existed in Boston, Lincolnshire, England.

York Carmelite Friary was a friary in York, North Yorkshire, England, that was established in about 1250, moved to its permanent site in 1295 and was surrendered in 1538.

The buildings known as Whitefriars are the surviving fragments of a Carmelite friary founded in 1342 in Coventry, England. All that remains are the eastern cloister walk, a postern gateway in Much Park Street and the foundations of the friary church. It was initially home to a friary until the dissolution of the monasteries. During the 16th century it was owned by John Hales and served as King Henry VIII School, Coventry, before the school moved to St John's Hospital, Coventry. It was home to a workhouse during the 19th century. The buildings are currently used by Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Austin Friars, London was an Augustinian friary in the City of London from its foundation, probably in the 1260s, until its dissolution in November 1538. It covered an area of about 5.5 acres a short distance to the north-east of the modern Bank of England and had a resident population of about 60 friars. A church stood at the centre of the friary precinct, with a complex of buildings behind it providing accommodation, refreshment and study space for the friars and visiting students. A large part of the friary precinct was occupied by gardens that provided vegetables, fruit and medicinal herbs.

Nottingham Whitefriars is a former Carmelite monastery located in Nottingham, England.

This is a list of the etymology of street names in the City of London.

Hanging Sword Alley is an alley in the Alsatia district of London, running between Whitefriars Street and Salisbury Square, close to Fleet Street.