The wolverine, also referred to as the glutton, carcajou, or quickhatch, is the largest land-dwelling species of the family Mustelidae. It is a muscular carnivore and a solitary animal. The wolverine has a reputation for ferocity and strength out of proportion to its size, with the documented ability to kill prey many times larger than itself.

The reindeer or caribou is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. This includes both sedentary and migratory populations. It is the only representative of the genus Rangifer. Herd size varies greatly in different geographic regions. More recent studies suggest the splitting of reindeer and caribou into six distinct species over their range.

The Canada lynx, or Canadian lynx, is a medium-sized North American lynx that ranges across Alaska, Canada, and northern areas of the contiguous United States. It is characterized by its long, dense fur, triangular ears with black tufts at the tips, and broad, snowshoe-like paws. Its hindlimbs are longer than the forelimbs, so its back slopes downward to the front. The Canada lynx stands 48–56 cm (19–22 in) tall at the shoulder and weighs between 5 and 17 kg. The lynx is a good swimmer and an agile climber. The Canada lynx was first described by Robert Kerr in 1792. Three subspecies have been proposed, but their validity is doubted; it is mostly considered a monotypic species.

The Innoko National Wildlife Refuge is a national wildlife refuge of the United States located in western Alaska. It consists of 3,850,481 acres (15,582 km2), of which 1,240,000 acres (5,018 km2) is designated a wilderness area. It is the fifth-largest national wildlife refuge in the United States. The refuge is administered from offices in Galena.

Selawik National Wildlife Refuge in northwest Alaska in the Waring Mountains was officially established in 1980 with the passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA).

The Canadian Wildlife Service or CWS, is a Branch of the Department of Environment and Climate Change Canada, a department of the Government of Canada. November 1, 2012 marked the 65th anniversary of the founding of Service.

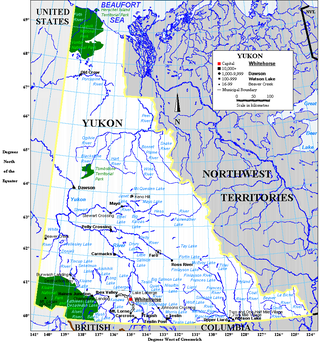

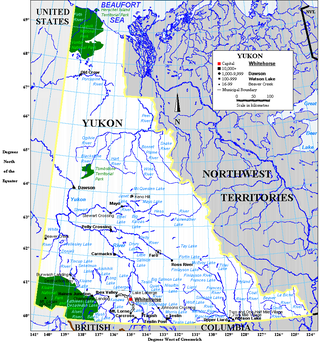

Yukon is in the northwestern corner of Canada and is bordered by Alaska and the Northwest Territories. The sparsely populated territory abounds with natural scenic beauty, with snowmelt lakes and perennial white-capped mountains, including many of Canada's highest mountains. The territory's climate is Arctic in territory north of Old Crow, subarctic in the region, between Whitehorse and Old Crow, and humid continental climate south of Whitehorse and in areas close to the British Columbia border. Most of the territory is boreal forest with tundra being the main vegetation zone only in the extreme north and at high elevations.

Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative or Y2Y is a transboundary Canada–United States not-for-profit organization that aims to connect and protect the 2,000 miles Yellowstone-to-Yukon region. Its mission proposes to maintain and restore habitat integrity and connectivity along the spine of North America's Rocky Mountains stretching from the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem to Canada's Yukon Territory. It is the only organization dedicated to securing the long-term ecological health of the region.

The migratory woodland caribou refers to two herds of Rangifer tarandus that are included in the migratory woodland ecotype of the subspecies Rangifer tarandus caribou or woodland caribou that live in Nunavik, Quebec, and Labrador: the Leaf River caribou herd (LRCH) and the George River caribou herd (GRCH) south of Ungava Bay. Rangifer tarandus caribou is further divided into three ecotypes: the migratory barren-ground ecotype, the mountain ecotype or woodland (montane) and the forest-dwelling ecotype. According to researchers, the "George River herd which morphologically and genetically belong to the woodland caribou subspecies, at one time represented the largest caribou herd in the world and migrating thousands of kilometers from boreal forest to open tundra, where most females calve within a three-week period. This behaviour is more like barren-ground caribou subspecies." They argued that "understanding ecotype in relation to existing ecological constraints and releases may be more important than the taxonomic relationships between populations." The migratory George River caribou herd travel thousands of kilometres moving from wintering grounds to calving grounds near the Inuit hamlet of Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik. In Nunavik and Labrador, the caribou population varies considerably with their numbers peaking in the later decades of each of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. In 1984, about 10,000 caribou of the George River herd drowned during their bi-annual crossing of the Caniapiscau River during the James Bay Hydro Project flooding operation. The most recent decline at the turn of the 20th century caused much hardship for the Inuit and Cree communities of Nunavik, who hunt them for subsistence.

The Porcupine caribou(Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) is a herd or ecotype of barren-ground caribou, the subspecies of the reindeer or caribou found in Alaska, United States, and Yukon and the Northwest Territories, Canada. A recent revision changes the Latin name; see Taxonomy.

Pink Mountain Provincial Park is a provincial park in British Columbia, Canada.

The Peary caribou is a subspecies of caribou found in the High Arctic islands of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories in Canada. They are the smallest of the North American caribou, with the females weighing an average of 60 kg (130 lb) and the males 110 kg (240 lb). In length the females average 1.4 m and the males 1.7 m.

The Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge is a United States National Wildlife Refuge covering about 19.16 million acres (77,500 km2) in southwestern Alaska. It is the second-largest National Wildlife Refuge in the country, only slightly smaller than the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It is a coastal plain extending to the Bering Sea, covering the delta created by the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers. The delta includes extensive wetlands near sea level that are often inundated by Bering Sea tides. It is bordered on the east by Wood-Tikchik State Park, the largest state park in the United States. The refuge is administered from offices in Bethel.

The wildlife of Canada or biodiversity of Canada consist of over 80,000 classified species, and an equal number thought yet to be recognized. Known fauna and flora have been identified from five kingdoms: protozoa represent approximately 1% of recorded species; chromist ; fungis ; plants ; and animals. Insects account for nearly 70 percent of documented animal species in Canada. More than 300 species are found exclusively in Canada.

Kanuti National Wildlife Refuge is a national wildlife refuge in central Alaska, United States. One of 16 refuges in Alaska, it was established in 1980 when Congress passed The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). At 1,640,000 acres (6,600 km2), Kanuti Refuge is about the size of the state of Delaware. Located at the Arctic Circle, the refuge is a prime example of Alaska's boreal ecosystem. It is dominated by black and white spruce, with some white birch and poplars.

The Koyukuk National Wildlife Refuge is a 3,500,000-acre (14,000 km2) conservation area in Alaska. It lies within the floodplain of the Koyukuk River, in a basin that extends from the Yukon River to the Purcell Mountains and the foothills of the Brooks Range. This region of wetlands is home to fish, waterfowl, beaver and Alaskan moose, and wooded lowlands where two species of fox, bears, wolf packs, Canadian lynx and marten prowl.

The boreal woodland caribou, also known as eastern woodland caribou, boreal forest caribou and forest-dwelling caribou, is a North American subspecies of reindeer found primarily in Canada with small populations in the United States. Unlike the Porcupine caribou and barren-ground caribou, boreal woodland caribou are primarily sedentary.

Dolphin and Union Caribou, Dolphin and Union caribou herd, Dolphin-Union, locally known as Island Caribou, are a migratory population of barren-ground caribou, Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus, that occupy Victoria Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and the nearby mainland. They are endemic to Canada. They migrate across the Dolphin and Union Strait from their summer grazing on Victoria Island to their winter grazing area on the Nunavut-Northwest Territories mainland in Canada. It is unusual for North American caribou to seasonally cross sea ice and the only other caribou to do so are the Peary caribou who are smaller in size and population. They were listed as Endangered by Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) since November 2017.

Caribou herds in Canada are discrete populations of seven subspecies that are represented in Canada. Caribou can be found from the High Arctic region south to the boreal forest and Rocky Mountains and from the east to the west coasts.

The reindeer is a widespread and numerous species in the northern Holarctic, being present in both tundra and taiga. Originally, the reindeer was found in Scandinavia, eastern Europe, Russia, Mongolia, and northern China north of the 50th latitude. In North America, it was found in Canada, Alaska, and the northern contiguous USA from Washington to Maine. In the 19th century, it was apparently still present in southern Idaho. It also occurred naturally on Sakhalin, Greenland, and probably even in historical times in Ireland.