Related Research Articles

Witchcraft, as most commonly understood in both historical and present-day communities, is the use of alleged supernatural powers of magic. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination of contemporaries than in any objective reality. Yet this stereotype has a long history and has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world." The belief in witchcraft has been found in a great number of societies worldwide. Anthropologists have applied the English term "witchcraft" to similar beliefs in occult practices in many different cultures, and societies that have adopted the English language have often internalised the term.

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, nineteen of whom were executed by hanging. One other man, Giles Corey, died under torture after refusing to enter a plea, and at least five people died in jail.

Matthew Hopkins was an English witch-hunter whose career flourished during the English Civil War. He was mainly active in East Anglia and claimed to hold the office of Witchfinder General, although that title was never bestowed by Parliament.

Bridget Bishop was the first person executed for witchcraft during the Salem witch trials in 1692. Nineteen were hanged, and one, Giles Corey, was pressed to death. Altogether, about 200 people were tried.

The Chesapeake Colonies were the Colony and Dominion of Virginia, later the Commonwealth of Virginia, and Province of Maryland, later Maryland, both colonies located in British America and centered on the Chesapeake Bay. Settlements of the Chesapeake region grew slowly due to diseases such as malaria. Most of these settlers were male immigrants from England who died soon after their arrival. Due to the majority of men, eligible women did not remain single for long. The native-born population eventually became immune to the Chesapeake diseases and these colonies were able to continue through all the hardships.

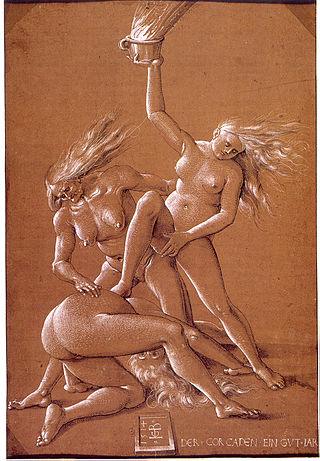

European witchcraft is a multifaceted historical and cultural phenomenon that unfolded over centuries, leaving a mark on the continent's social, religious, and legal landscapes. The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

The Bury St Edmunds witch trials were a series of trials conducted intermittently between the years 1599 and 1694 in the town of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk, England.

In the early modern period, from about 1400 to 1775, about 100,000 people were prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe and British America. Between 40,000 and 60,000 were executed. The witch-hunts were particularly severe in parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Prosecutions for witchcraft reached a high point from 1560 to 1630, during the Counter-Reformation and the European wars of religion. Among the lower classes, accusations of witchcraft were usually made by neighbors, and women made formal accusations as much as men did. Magical healers or 'cunning folk' were sometimes prosecuted for witchcraft, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused. Roughly 80% of those convicted were women, most of them over the age of 40. In some regions, convicted witches were burnt at the stake.

Thomas Brattle was an American merchant who served as treasurer of Harvard College and member of the Royal Society. He is known for his involvement in the Salem Witch Trials and the formation of the Brattle Street Church.

Beyond the Witch Trials: Witchcraft and Magic in Enlightenment Europe is an edited volume edited by the historians Owen Davies and Willem de Blécourt. It was first published by Manchester University Press in 2004. It consists of ten essays on the continued practice of magic and the belief in witchcraft in Europe during the European Enlightenment after the end of the witch trials in the early modern period. It was accompanied by Witchcraft Continued: Popular Magic in Modern Europe, dealing with the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, also published by Manchester University Press in 2004.

In early modern Scotland, in between the early 16th century and the mid-18th century, judicial proceedings concerned with the crimes of witchcraft took place as part of a series of witch trials in Early Modern Europe. In the late middle age there were a handful of prosecutions for harm done through witchcraft, but the passing of the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. The first major issue of trials under the new act were the North Berwick witch trials, beginning in 1590, in which King James VI played a major part as "victim" and investigator. He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the Daemonologie in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions.

Women in early modern Scotland, between the Renaissance of the early sixteenth century and the beginnings of industrialisation in the mid-eighteenth century, were part of a patriarchal society, though the enforcement of this social order was not absolute in all aspects. Women retained their family surnames at marriage and did not join their husband's kin groups. In higher social ranks, marriages were often political in nature and the subject of complex negotiations in which women as matchmakers or mothers could play a major part. Women were a major part of the workforce, with many unmarried women acting as farm servants and married women playing a part in all the major agricultural tasks, particularly during harvest. Widows could be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading, but many at the bottom of society lived a marginal existence.

Grace White Sherwood (1660–1740), called the Witch of Pungo, is the last person known to have been convicted of witchcraft in Virginia.

The great Scottish witch hunt of 1649–50 was a series of witch trials in Scotland. It is one of five major hunts identified in early modern Scotland and it probably saw the most executions in a single year.

The Witch trials in Portugal were perhaps the fewest in all of Europe. Similar to the Spanish Inquisition in neighboring Spain, the Portuguese Inquisition preferred to focus on the persecution of heresy and did not consider witchcraft to be a priority. In contrast to the Spanish Inquisition, however, the Portuguese Inquisition was much more efficient in preventing secular courts from conducting witch trials, and therefore almost managed to keep Portugal free from witch trials. Only seven people are known to have been executed for sorcery in Portugal.

During a 104-year period from 1626 to 1730, there are documented Virginia Witch Trials, hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Colonial Virginia. More than two dozen people are documented having been accused, including two men. Virginia was the first colony to have a formal accusation of witchcraft in 1626, and the first formal witch trial in 1641.

Goodwife Joan Wright, called ''Surry's Witch," is the first person known to have been legally accused of witchcraft in any British North American colony.

Anna Hack Boot was an early Dutch settler in Early America who carried on extensive trading activities throughout the Atlantic. Anna was one of the first women business owners and entrepreneurs in America. According to historians, Anna's life serves as an example of how Dutch women in early modern Europe and America were "more commonly engaged in long-distance trade" than women from other backgrounds, and "acted as merchants and as their husband's business partners."

The views of witchcraft in North America have evolved through an interlinking history of cultural beliefs and interactions. These forces contribute to complex and evolving views of witchcraft. Today, North America hosts a diverse array of beliefs about witchcraft.

References

- ↑ Burr, George Lincoln (1914). Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648-1706. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 435. ISBN 9780722266083.

- ↑ Meyers, Debra; Perreault, Melanie (2014-07-16). Order and Civility in the Early Modern Chesapeake. Lexington Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7391-8975-7.

- ↑ Sobel, Mechal (2021-06-08). The World They Made Together: Black and White Values in Eighteenth-Century Virginia. Princeton University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4008-2049-8.

- ↑ Waring, Lucy Lemoine (1971). Hardings of Northumberland County, Virginia, and Their Related Families: Mini-history, Homes and Churches. The author.

- ↑ Marion Nugent, Nell. Virginia Land Patents and Grants, 1623 -1800. p. 337.

- ↑ Gipson, Lawrence H. (1998). Revisioning the British Empire in the Eighteenth Century: Essays from Twenty-five Years of the Lawrence Henry Gipson Institute for Eighteenth-Century Studies. Lehigh University Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-934223-57-7.

- ↑ Bruce, Philip Alexander (1910). Institutional History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century: An Inquiry Into the Religious, Moral and Educational, Legal, Military, and Political Condition of the People Based on Original and Contemporaneous Records. G.P. Putnam's sons. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-598-84156-8.

- ↑ Moyer, Paul B. (2020-10-15). Detestable and Wicked Arts: New England and Witchcraft in the Early Modern Atlantic World. Cornell University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-5017-5106-6.

- ↑ Picariello, Damien K. (2020-06-26). The Politics of Horror. Springer Nature. p. 163. ISBN 978-3-030-42015-4.

- ↑ Wertenbaker, Thomas J. (1927). The First Americans. p. 146.

- ↑ Scott, Arthur Pearson (1930). Criminal Law in Colonial Virginia. University of Chicago Press. p. 240.

- ↑ Laulainen-Schein, Diana Lyn (2004). Comparative Counterpoints: Witchcraft Accusations in Early Modern Lancashire and the Chesapeake. University of Minnesota. p. 314.

- ↑ Sheppard, Nancy E. (2018-10-08). Hampton Roads Murder & Mayhem. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-6538-1.

- ↑ Booth, Sally Smith (1975). The Witches of Early America. Hastings House. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-8038-8072-6.

- ↑ Beau, Bryan F. Le (2016-05-23). The Story of the Salem Witch Trials. Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-315-50904-4.

- 1 2 Hines, Emilee (2010-08-17). Mysteries and Legends of Virginia: True Stories of the Unsolved and Unexplained. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7627-6657-4.

- ↑ Porterfield, Amanda; Corrigan, John (2010-04-26). Religion in American History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-6137-4.

- ↑ Hudson Jr., Carson O. Witchcraft in Colonial Virginia. The History Press. 2019. ISBN 978-1-4671-4424-7

- ↑ Blanton, Wyndham Bolling (1972). Medicine in Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. Arno Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-405-03936-2.