Dhimmī or muʿāhid (معاهد) is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligation under sharia to protect the individual's life, property, as well as freedom of religion, in exchange for loyalty to the state and payment of the jizya tax, in contrast to the zakat, or obligatory alms, paid by the Muslim subjects. Dhimmi were exempt from certain duties assigned specifically to Muslims if they paid the poll tax (jizya) but were otherwise equal under the laws of property, contract, and obligation.

Medina, officially Al-Madinah al-Munawwarah and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah, is the capital of Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia. One of the most sacred cities in Islam, the population as of 2022 is 1,411,599, making it the fifth-most populous city in the country. Around 58.5% of the population are Saudi citizens and 41.5% are foreigners. Located at the core of the Medina Province in the western reaches of the country, the city is distributed over 589 km2 (227 sq mi), of which 293 km2 (113 sq mi) constitutes the city's urban area, while the rest is occupied by the Hejaz Mountains, empty valleys, agricultural spaces and older dormant volcanoes.

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member of the clan. The family established dynastic, hereditary rule with Mu'awiya I, the long-time governor of Greater Syria, who became caliph after the end of the First Fitna in 661. After Mu'awiya's death in 680, conflicts over the succession resulted in the Second Fitna, and power eventually fell to Marwan I, from another branch of the clan. Syria remained the Umayyads' main power base thereafter, with Damascus as their capital.

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb is an Islamic term referring to followers of those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are identified as the Jews, the Christians, the Sabians, and—according to some interpretations—the Zoroastrians. Starting from the 8th century, some Muslims also recognized other religious groups such as the Samaritans, and even Buddhists, Hindus, and Jains, as People of the Book.

Umar ibn al-Khattab was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634, when he succeed Abu Bakr as the second caliph, until his assassination in 644. Umar was a senior companion and father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Scholars have studied and debated Muslim attitudes towards Jews, as well as the treatment of Jews in Islamic thought and societies throughout the history of Islam. Parts of the Islamic literary sources give mention to certain Jewish groups present in the past or present, which has led to debates. Some of this overlaps with Islamic remarks on non-Muslim religious groups in general.

Islamic–Jewish relations comprise the human and diplomatic relations between Jewish people and Muslims in the Arabian Peninsula, Northern Africa, the Middle East, and their surrounding regions. Jewish–Islamic relations may also refer to the shared and disputed ideals between Judaism and Islam, which began roughly in the 7th century CE with the origin and spread of Islam in the Arabian peninsula. The two religions share similar values, guidelines, and principles. Islam also incorporates Jewish history as a part of its own. Muslims regard the Children of Israel as an important religious concept in Islam. Moses, the most important prophet of Judaism, is also considered a prophet and messenger in Islam. Moses is mentioned in the Quran more than any other individual, and his life is narrated and recounted more than that of any other prophet. There are approximately 43 references to the Israelites in the Quran, and many in the Hadith. Later rabbinic authorities and Jewish scholars such as Maimonides discussed the relationship between Islam and Jewish law. Maimonides himself, it has been argued, was influenced by Islamic legal thought.

Jizya is a tax historically levied on dhimmis, that is, protected non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. When the Qur'an was written, it was common inside and outside of Arabia to levy poll taxes against alien groups. Building upon the historical practice, classical Muslim jurists argued that the poll tax is money collected by the Islamic polity from non-Muslims in return for the protection of the Muslim state. Quote: Jizyah: Compensation. Poll tax levied on non-Muslims, such as Jews and Christians, as a form of tribute and in exchange for an exemption from military service, based on Quran 9:29. The Quran and hadiths mention jizya without specifying its rate or amount, and the application of jizya varied in the course of Islamic history. However, scholars largely agree that early Muslim rulers adapted some of the existing systems of taxation and modified them according to Islamic religious law.

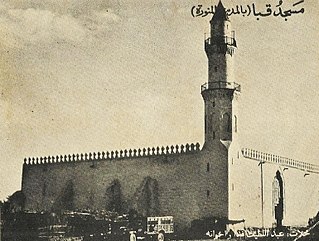

The Quba Mosque is a mosque located in Medina, in the Hejazi region of Saudi Arabia, built in the lifetime of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the 7th century C.E. It is thought to be the first mosque in the world, built on the first day of Muhammad's emigration to Medina. Its first stone is said to have been laid by the prophet, and the structure completed by his companions.

Over the centuries of Islamic history, Muslim rulers, Islamic scholars, and ordinary Muslims have held many different attitudes towards other religions. Attitudes have varied according to time, place and circumstance.

The military career of Muhammad, the Islamic prophet, encompasses several expeditions and battles throughout the Hejaz region in the western Arabian Peninsula which took place in the final ten years of his life, from 622 to 632. His primary campaign was against his own tribe in Mecca, the Quraysh. Muhammad proclaimed prophethood around 610 and later migrated to Medina after being persecuted by the Quraysh in 622. After several battles against the Quraysh, Muhammad conquered Mecca in 629, ending his campaign against the tribe.

The Battle of Khaybar was an armed confrontation between the early Muslims and the Jewish community of Khaybar in 628 CE.

Seeing Islam As Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam from the Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam series is a book by scholar of the Middle East Robert G. Hoyland.

The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians Under Islam is a history book on the dhimmi peoples - the non-Arab and non-Muslim communities subjected to Muslim domination after the conquest of their territories by Arabs by Bat Ye'or. The book was first published in French in 1980, and was titled Le Dhimmi : Profil de l'opprimé en Orient et en Afrique du Nord depuis la conquête Arabe. It was translated into English and published in 1985 under the name The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians Under Islam. The book provides a wealth of documents from diverse periods and regions, many of them previously unpublished and makes a clear distinction between factual history and biased interpretations, providing a comprehensive study of dhimmi populations that draws on numerous original source materials to convey an accurate portrait of their status under Islamic rule.

The Pact of Umar is a treaty between the Muslims and the non-Muslim inhabitants of either Levant, Mesopotamia (Iraq) or Jerusalem that later gained a canonical status in Islamic jurisprudence. It specifies rights and restrictions for dhimmis, or "people of the book," a type of protected class of non-Muslim peoples recognized by Islam which includes Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, and several other recognized faiths living under Islamic rule. There are several versions of the pact, differing both in structure and stipulations. While the pact is traditionally attributed to the second Rashidun Caliph Umar ibn Khattab, other jurists and orientalists have questioned this attribution with the treaty being instead attributed to 9th century Mujtahids or the Umayyad Caliph Umar II. This treaty should not be confused with Umar's Assurance of safety to the people of Aelia.

The Rashidun Caliphate was the first caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was ruled by the first four successive caliphs of Muhammad after his death in 632 CE. During its existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in West Asia and Northeast Africa.

The persecution of Zoroastrians has been recorded throughout the history of Zoroastrianism, an Iranian religion. The notably large-scale persecution of Zoroastrians began after the rise of Islam in the 7th century CE; both during and after the conquest of Persia by Arab Muslims, discrimination and harassment against Zoroastrians took place in the form of forced conversions and sparse violence. Muslims who arrived in the region after its annexation by the Rashidun Caliphate are recorded to have destroyed Zoroastrian temples, and Zoroastrians living in areas that had fallen under Muslim control were required to pay a tax known as jizya.

The Islamization of Egypt occurred after the 7th century Arab conquest of Egypt, in which the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate seized control of Egypt from the Christian Byzantine Empire. Egypt and other conquered territories in the Middle East underwent a large scale gradual conversion from Christianity to Islam, accompanied by jizya for those who refused to convert. Islam became the dominant faith by the 10th to 12th centuries, and Arabic replaced Coptic as the vernacular language and Greek as the official language.

Winemaking has a long tradition in Egypt dating back to the 3rd millennium BC. The modern wine industry is relatively small scale but there have been significant strides towards reviving the industry. In the late nineties the industry invited international expertise in a bid to improve the quality of Egyptian wine, which used to be known for its poor quality. In recent years Egyptian wines have received some recognition, having won several international awards. In 2013 Egypt produced 4,500 tonnes of wine, ranking 54th globally, ahead of Belgium and the United Kingdom.

Khamr is an Arabic word for wine or intoxicant. It is variously defined as alcoholic beverages, wine or liquor.