Related Research Articles

Chiang Kai-shek was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and military leader. He was the head of the Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party, General of the National Revolutionary Army, known as Generalissimo, and the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) in mainland China from 1928 until 1949. After being defeated in the Chinese Civil War by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1949, he led the ROC on the island of Taiwan until his death in 1975.

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and the forces of the Chinese Communist Party, with armed conflict continuing intermittently from 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949, resulting in a Communist victory and control of mainland China in the Chinese Communist Revolution.

The Second Sino-Japanese War was the war fought between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan from 1937 to 1945 as part of World War II. It is often regarded as the beginning of World War II in Asia. It was the largest Asian war in the 20th century and has been described as "the Asian Holocaust", in reference to the scale of Japanese war crimes against Chinese civilians. It is known in Japan as the Second China–Japan War, and in China as the Chinese War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

Foot binding, or footbinding, was the Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls to change their shape and size. Feet altered by footbinding were known as lotus feet and the shoes made for them were known as lotus shoes. In late imperial China, bound feet were considered a status symbol and a mark of feminine beauty. However, footbinding was a painful practice that limited the mobility of women and resulted in lifelong disabilities.

Bai Chongxi was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China (ROC) and a prominent Chinese Nationalist leader. He was of Hui ethnicity and of the Muslim faith. From the mid-1920s to 1949, Bai and his close ally Li Zongren ruled Guangxi province as regional warlords with their own troops and considerable political autonomy. His relationship with Chiang Kai-shek was at various times antagonistic and cooperative. He and Li Zongren supported the anti-Chiang warlord alliance in the Central Plains War in 1930, then supported Chiang in the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War. Bai was the first defense minister of the Republic of China from 1946 to 1948. After losing to the Communists in 1949, he fled to Taiwan, where he died in 1966.

The Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in eastern China. It existed alongside the Nationalist government of the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-shek, which was fighting Japan along with the other Allies of World War II. The country functioned as a dictatorship under Wang Jingwei, formerly a high-ranking official of the Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT). The region it administered was initially seized by Japan during the late 1930s at the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Operation Ichi-Go was a campaign of a series of major battles between the Imperial Japanese Army forces and the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China, fought from April to December 1944. It consisted of three separate battles in the Chinese provinces of Henan, Hunan and Guangxi.

The term "home front" covers the activities of the civilians in a nation at war. World War II was a total war; homeland military production became vital to both the Allied and Axis powers. Life on the home front during World War II was a significant part of the war effort for all participants and had a major impact on the outcome of the war. Governments became involved with new issues such as rationing, manpower allocation, home defense, evacuation in the face of air raids, and response to occupation by an enemy power. The morale and psychology of the people responded to leadership and propaganda. Typically women were mobilized to an unprecedented degree.

In Chinese culture, the word hanjian is a pejorative term for a traitor to the Han Chinese state and, to a lesser extent, Han ethnicity. The word hanjian is distinct from the general word for traitor, which could be used for any country or ethnicity. As a Chinese term, it is a digraph of the Chinese characters for "Han" and "traitor". Han is the majority ethnic group in China; and Jian, in Chinese legal language, primarily referred to illicit sex. Implied by this term was a Han Chinese carrying on an illicit relationship with the enemy. Hanjian is often worded as "collaborator" in the West.

The 1938 Yellow River flood was a man-made flood from June 1938 to January 1947 created by the Chinese National Army's intentional destruction of dikes (levees) on the Yellow River in Huayuankou, Henan Province. The first wave of floods hit Zhongmu County on 13 June 1938.

Ikuhiko Hata is a Japanese historian. He earned his PhD at the University of Tokyo and has taught history at several universities. He is the author of a number of influential and well-received scholarly works, particularly on topics related to Japan's role in the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

Like women in many other cultures, women in China have been historically oppressed. For thousands of years, women in China lived under the patriarchal social order characterized by the Confucius teaching of "filial piety". In modern China, the lives of women have changed significantly due to the late Qing dynasty reforms, the changes of the Republican period, the Chinese Civil War, and the rise of the People's Republic of China (PRC).

The recorded military history of China extends from about 2200 BC to the present day. This history can be divided into the military history of China before 1912, when a revolution overthrew the imperial state, and the period of the Republic of China Army and the People's Liberation Army.

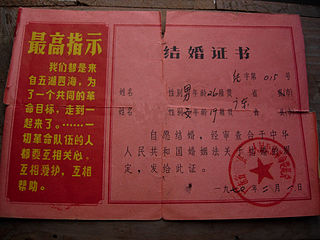

The New Marriage Law was a civil marriage law passed in the People's Republic of China on May 1, 1950. It was a radical change from existing patriarchal Chinese marriage customs, and needed constant support from propaganda campaigns. It has since been superseded by the Second Marriage Law of 1980. It was formally repealed by the Civil Code in 2021.

The Henan Famine of 1942–1943 occurred in Henan, most particularly within the eastern and central part of the province. The famine occurred within the context of the Second Sino-Japanese War and resulted from a combination of natural and human factors. Modern quantitative studies put the death toll to be "well under one million", probably around 700,000. 15 years later Henan was struck by the deadlier Great Chinese famine.

Xia Douyin (1885–1951) was a Republic of China National Revolutionary Army general. He was born in Macheng, Hubei. Originally a member of the Qing Dynasty New Army, he participated in the Xinhai Revolution of 1911. In 1917, he joined the Constitutional Protection Movement and opposed local warlord Wang Zhanyuan. Defeated by Wang's forces, he fled to Changsha and enlisted the help of allies in Hunan against Wang. After suffering another defeat in 1919, he fled to the border region of Hunan and Jiangxi Provinces. In 1926, he was brought by Tang Shengzhi into the National Revolutionary Army and participated in the Northern Expedition as a divisional commander. On May 17, 1927, Xia led Kuomintang forces loyal to Chiang Kai-shek from Yichang against the forces of Ye Ting in Wuhan. After his victory, he notoriously took personal pleasure in mutilating the corpses of female revolutionaries he had killed. Chiang promoted Xia to army commander and he fought in the Central Plains War of 1930. Xia was then tasked with suppressing the Eyuwan Soviet in the border region between Hubei, Henan, and Anhui provinces. He ordered the massacre of thousands of civilians but was unable to stop the Communists' expansion. In 1932, Xia was promoted to full general and made governor of Hubei, although Zhang Qun actually acted in his place. From July to September 1932, Chiang Kai-shek ordered 300,000 troops of the National Revolutionary Army to surround and suppress the Eyuwan Soviet in the Fourth Encirclement Campaign. Xia directed a scorched earth campaign, killing all men found in the Soviet areas, burning all buildings, and seizing or destroying all crops. He was ultimately successful and the main Communist Red Army was forced to retreat westwards. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Xia fled to Chengdu after Hubei was occupied by the invading Imperial Japanese Army. In 1945, he retired from the military. Although he attempted to welcome the Communist Party of China takeover of the mainland, the communists rebuffed him and he fled to Hong Kong, where he died.

He Luli was a Chinese politician and paediatrician. She entered politics after practicing medicine for 27 years, serving as Vice-Mayor of Beijing, Chairwoman of the Revolutionary Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang, Vice Chairperson of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, and Vice Chairperson of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress.

He Siyuan, also spelled Ho Shih-yuan, was a Chinese educator, politician and guerrilla leader. Educated in China, the United States, and France, he was an economics professor at Sun Yat-sen University and education minister of Shandong Province. When Japan invaded China in 1937, he organized a guerrilla force to fight the resistance war in Shandong, and was the wartime governor of the province. He later became Mayor of Beijing until he negotiated to surrender to communist forces when KMT was losing. He survived Chiang's two attempts to assassinate him, but lost his youngest daughter in the second attack. In 1949 he negotiated the peaceful surrender of Beijing to the Communist forces, ensuring the safety of its millions of residents. Fluent in four European languages, after 1949 he mainly worked on translating foreign publications into Chinese. His elder daughter, He Luli, grew up to become Vice-Mayor of Beijing and Chairwoman of the Revolutionary Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang.

The National Christian Council of China (NCC) was a Protestant organization in China. Its members were both Chinese Protestant churches and foreign missionary societies and its purpose was to promote cooperation among these churches and societies. The NCC was formed in 1922 in the aftermath of the Edinburgh Missionary Conference.

This bibliography covers the English language scholarship of major studies in Chinese history.

References

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 190.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 18.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 3.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. pp. 55, 106.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 58.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 108.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 71.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 184.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 73.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 65.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 21.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 97.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 40.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 52.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 42–43, 139.

- ↑ Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. pp. 1–2, 82.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 207.

- ↑ Muscolino, Micah (2015). The Ecology of War in China: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 151.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 58.

- 1 2 Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 84.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 83.

- ↑ Muscolino, Micah (2015). The Ecology of War in China: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 78.

- ↑ Muscolino, Micah (2015). The Ecology of War in China: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Chen, Janet Y. (2012). Guilty of Indigence: The Urban Poor in China, 1900–1953. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 147.

- ↑ Muscolino, Micah (2015). The Ecology of War in China: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 170.

- ↑ Lary, Diana (2010). The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 68.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 57–8.

- ↑ Mitter, Rana (2013). China's War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival. London: Allen Lane. p. 131.

- ↑ Mitter, Rana (2013). China's War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival. London: Allen Lane. pp. 132–3.

- ↑ Mitter, Rana (2013). China's War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival. London: Allen Lane. p. 134.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 181.

- ↑ Lary, Diana (2010). Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 25.

- ↑ Lary, Diana (2010). The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 100.

- 1 2 Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 188.

- ↑ Lary, Diana (2010). The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–3.

- ↑ Lary, Diana (2010). The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 98.

- ↑ Lary, Diana (2010). The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 5.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 187.

- ↑ Li, Danke (2010). Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 63.

- ↑ Muscolino, Micah (2015). The Ecology of War in China: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 154.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 186–7.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 189.

- ↑ Lary, Diana (2010). The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 97.

- ↑ Goodman, David S. G. (2000). "Revolutionary Women and Women in the Revolution: The Chinese Communist Party and Women in the War of Resistance to Japan, 1937–1945". The China Quarterly (164): 929.

- 1 2 Lary, Diana (2010). The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 99.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 182.

- 1 2 Barnes, Nicole Elizabeth (2018). Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China,1937–1945. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. pp. 62–63.