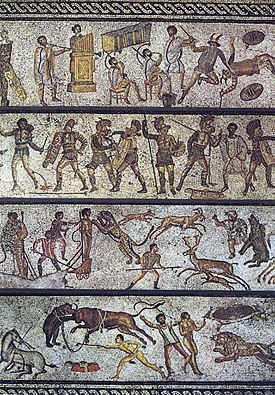

A gladiator was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing by appearing in the arena. Most were despised as slaves, schooled under harsh conditions, socially marginalized, and segregated even in death.

Fishbourne Roman Palace is located in the village of Fishbourne, Chichester in West Sussex. The palace is the largest Roman residence north of the Alps. and has an unusually early date of 75 AD, around thirty years after the Roman conquest of Britain.

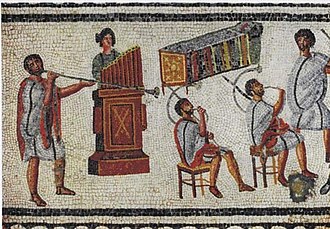

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly popular in the Ancient Roman world.

Torre del Greco is a comune in the Metropolitan City of Naples in Italy, with a population of c. 85,000 as of 2016. The locals are sometimes called Corallini because of the once plentiful coral in the nearby sea, and because the city has been a major producer of coral jewellery and cameo brooches since the seventeenth century.

Sabratha, in the Zawiya District of Libya, was the westernmost of the ancient "three cities" of Roman Tripolis, alongside Oea and Leptis Magna. From 2001 to 2007 it was the capital of the former Sabratha wa Sorman District. It lies on the Mediterranean coast about 70 km (43 mi) west of modern Tripoli. The extant archaeological site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982.

Heraclea Lyncestis, also spelled Herakleia Lynkestis, was an ancient Greek city in Macedon, ruled later by the Romans. Its ruins are situated 2 km (1.2 mi) south of the present-day town of Bitola, North Macedonia. In the early Christian period, Heraclea was an important Episcopal seat and a waypoint on the Via Egnatia that once linked Byzantium with Rome through the Adriatic seaport Dyrrachium. Some of its bishops are mentioned in synods in Serdica and other nearby towns. The city was gradually abandoned in the 6th century AD following an earthquake and Slavic invasions.

Rusellae was an important ancient town of Etruria, which survived until the Middle Ages before being abandoned. The impressive archaeological remains lie near the modern frazione or village of Roselle in the comune of Grosseto.

Kourion was an important ancient Greek city-state on the southwestern coast of Cyprus. In the twelfth century BCE, after the collapse of the Mycenaean palaces, Greek settlers from Argos arrived on this site.

Thuburbo Majus is a large Roman site in northern Tunisia. It is located roughly 60 km southwest of Carthage on a major African thoroughfare. This thoroughfare connects Carthage to the Sahara. Other towns along the way included Sbiba, Sufes, Sbeitla, and Sufetula. Parts of the old Roman road are in ruins, but others do remain.

Hellenistic art is the art of the Hellenistic period generally taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a process well underway by 146 BCE, when the Greek mainland was taken, and essentially ending in 30 BCE with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Battle of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

Carranque is a town in the Toledo province, Castile-La Mancha, Spain. It is located in the area of the province bordering the province of Madrid called the Alta Sagra.

The House of the Cascade is a Roman-era building located in Utica, Tunisia. It is typical of most of the Roman houses excavated to date in North Africa in that it looks inwards to a central courtyard around which the majority of the rooms are arranged. Two smaller courtyard gardens in the western part of the house provided additional light and air.

Damnatio ad bestias was a form of Roman capital punishment where the condemned person was killed by wild animals, usually lions or other big cats. This form of execution, which first appeared during the Roman Republic around the 2nd century BC, had been part of a wider class of blood sports called Bestiarii.

Hairstyle fashion in Rome was ever changing, and particularly in the Roman Imperial Period there were a number of different ways to style hair. As with clothes, there were several hairstyles that were limited to certain people in ancient society. Styles are so distinctive they allow scholars today to create a chronology of Roman portraiture and art; we are able to date pictures of the empresses on coins, or identify busts depending on their hairstyles.

A Roman mosaic is a mosaic made during the Roman period, throughout the Roman Republic and later Empire. Mosaics were used in a variety of private and public buildings, on both floors and walls, though they competed with cheaper frescos for the latter. They were highly influenced by earlier and contemporary Hellenistic Greek mosaics, and often included famous figures from history and mythology, such as Alexander the Great in the Alexander Mosaic.

Aydın Archaeological Museum is in Aydın, western Turkey. Established in 1959, it contains numerous statues, tombs, columns and stone carvings from the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Seljuk and Ottoman periods, unearthed in ancient cities such as Alinda, Alabanda, Amyzon, Harpasa, Magnesia on the Maeander, Mastaura, Myus, Nisa, Orthosia, Piginda, Pygela and Tralleis. The museum also has a section devoted to ancient coin finds.

The mosaics of Delos are a significant body of ancient Greek mosaic art. Most of the surviving mosaics from Delos, Greece, an island in the Cyclades, date to the last half of the 2nd century BC and early 1st century BC, during the Hellenistic period and beginning of the Roman period of Greece. Hellenistic mosaics were no longer produced after roughly 69 BC, due to warfare with the Kingdom of Pontus and subsequently abrupt decline of the island's population and position as a major trading center. Among Hellenistic Greek archaeological sites, Delos contains one of the highest concentrations of surviving mosaic artworks. Approximately half of all surviving tessellated Greek mosaics from the Hellenistic period come from Delos.

Orbe-Boscéaz, also named Boscéay, is an archaeological site in Switzerland, located at the territory of the town of Orbe (Vaud).

Aïcha Ben Abed is an archaeologist and Director of Monuments and Sites at the Institut National du Patrimoine, Tunisia. She is one of the world's leading authorities on the mosaics of Roman Africa.

The Aïn Doura Baths are a series of Roman-era ruins located in Dougga, Tunisia. The site contains ruins from a Roman bath dating to the 4th century, and is considered an important archaeological heritage site by the National Heritage Institute of Tunisia.