Deaf culture is the set of social beliefs, behaviors, art, literary traditions, history, values, and shared institutions of communities that are influenced by deafness and which use sign languages as the main means of communication. When used as a cultural label especially within the culture, the word deaf is often written with a capital D and referred to as "big D Deaf" in speech and sign. When used as a label for the audiological condition, it is written with a lower case d. Carl G. Croneberg coined the term "Deaf Culture" and he was the first to discuss analogies between Deaf and hearing cultures in his appendices C/D of the 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language.

Signing Exact English is a system of manual communication that strives to be an exact representation of English language vocabulary and grammar. It is one of a number of such systems in use in English-speaking countries. It is related to Seeing Essential English (SEE-I), a manual sign system created in 1945, based on the morphemes of English words. SEE-II models much of its sign vocabulary from American Sign Language (ASL), but modifies the handshapes used in ASL in order to use the handshape of the first letter of the corresponding English word.

Interpreting is a translational activity in which one produces a first and final target-language output on the basis of a one-time exposure to an expression in a source language.

The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc (RID) is a non-profit organization founded on June 16, 1964, and incorporated in 1972, that seeks to uphold standards, ethics, and professionalism for American Sign Language interpreters. RID is currently a membership organization. The organization grants credentials earned by interpreters who have passed assessments for American Sign Language to English and English to American Sign Language interpretation and maintains their certificates by taking continuing education units. RID provides a Certification Maintenance Program (CMP) to certified members in support of skill-enhancing studies. The organization also provides the Ethical Practices System (EPS) for those who want to file grievances against members of RID. The organization also collaborated with the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) to develop the Code of Professional Conduct (CPC). The CPC Standard Practice Papers (SPP) are also available for professional interpreters to reference. RID is headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia.

Manually Coded English (MCE) is a type of sign system that follows direct spoken English. The different codes of MCE vary in the levels of directness in following spoken English grammar. There may also be a combination with other visual clues, such as body language. MCE is typically used in conjunction with direct spoken English.

Simultaneous communication, SimCom, or sign supported speech (SSS) is a technique sometimes used by deaf, hard-of-hearing or hearing sign language users in which both a spoken language and a manual variant of that language are used simultaneously. While the idea of communicating using two modes of language seems ideal in a hearing/deaf setting, in practice the two languages are rarely relayed perfectly. Often the native language of the user is the language that is strongest, while the non-native language degrades in clarity. In an educational environment this is particularly difficult for deaf children as a majority of teachers who teach the deaf are hearing. Results from surveys taken indicate that communication for students is indeed signing, and that the signing leans more toward English rather than ASL.

Audism as described by deaf activists is a form of discrimination directed against deaf people, which may include those diagnosed as deaf from birth, or otherwise. Tom L. Humphries coined the term in his doctoral dissertation in 1975, but it did not start to catch on until Harlan Lane used it in his writing. Humphries originally applied audism to individual attitudes and practices; whereas Lane broadened the term to include oppression of deaf people.

A video relay service (VRS), also sometimes known as a video interpreting service (VIS), is a video telecommunication service that allows deaf, hard-of-hearing, and speech-impaired (D-HOH-SI) individuals to communicate over video telephones and similar technologies with hearing people in real-time, via a sign language interpreter.

Bimodal bilingualism is an individual or community's bilingual competency in at least one oral language and at least one sign language, which utilize two different modalities. An oral language consists of a vocal-aural modality versus a signed language which consists of a visual-spatial modality. A substantial number of bimodal bilinguals are children of deaf adults (CODA) or other hearing people who learn sign language for various reasons. Deaf people as a group have their own sign language(s) and culture that is referred to as Deaf, but invariably live within a larger hearing culture with its own oral language. Thus, "most deaf people are bilingual to some extent in [an oral] language in some form". In discussions of multilingualism in the United States, bimodal bilingualism and bimodal bilinguals have often not been mentioned or even considered. This is in part because American Sign Language, the predominant sign language used in the U.S., only began to be acknowledged as a natural language in the 1960s. However, bimodal bilinguals share many of the same traits as traditional bilinguals, as well as differing in some interesting ways, due to the unique characteristics of the Deaf community. Bimodal bilinguals also experience similar neurological benefits as do unimodal bilinguals, with significantly increased grey matter in various brain areas and evidence of increased plasticity as well as neuroprotective advantages that can help slow or even prevent the onset of age-related cognitive diseases, such as Alzheimer's and dementia.

Video remote interpreting (VRI) is a videotelecommunication service that uses devices such as web cameras or videophones to provide sign language or spoken language interpreting services. This is done through a remote or offsite interpreter, in order to communicate with persons with whom there is a communication barrier. It is similar to a slightly different technology called video relay service, where the parties are each located in different places. VRI is a type of telecommunications relay service (TRS) that is not regulated by the FCC.

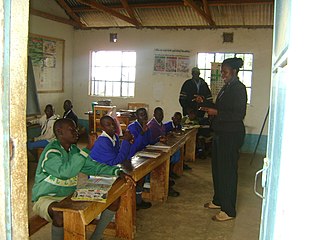

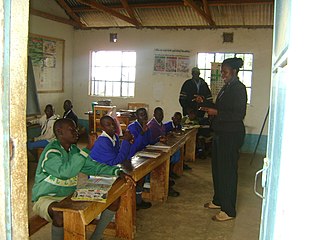

Deaf education is the education of students with any degree of hearing loss or deafness. This may involve, but does not always, individually-planned, systematically-monitored teaching methods, adaptive materials, accessible settings, and other interventions designed to help students achieve a higher level of self-sufficiency and success in the school and community than they would achieve with a typical classroom education. There are different language modalities used in educational setting where students get varied communication methods. A number of countries focus on training teachers to teach deaf students with a variety of approaches and have organizations to aid deaf students.

The sociolinguistics of sign languages is the application of sociolinguistic principles to the study of sign languages. The study of sociolinguistics in the American Deaf community did not start until the 1960s. Until recently, the study of sign language and sociolinguistics has existed in two separate domains. Nonetheless, now it is clear that many sociolinguistic aspects do not depend on modality and that the combined examination of sociolinguistics and sign language offers countless opportunities to test and understand sociolinguistic theories. The sociolinguistics of sign languages focuses on the study of the relationship between social variables and linguistic variables and their effect on sign languages. The social variables external from language include age, region, social class, ethnicity, and sex. External factors are social by nature and may correlate with the behavior of the linguistic variable. The choices made of internal linguistic variant forms are systematically constrained by a range of factors at both the linguistic and the social levels. The internal variables are linguistic in nature: a sound, a handshape, and a syntactic structure. What makes the sociolinguistics of sign language different from the sociolinguistics of spoken languages is that sign languages have several variables both internal and external to the language that are unique to the Deaf community. Such variables include the audiological status of a signer's parents, age of acquisition, and educational background. There exist perceptions of socioeconomic status and variation of "grassroots" deaf people and middle-class deaf professionals, but this has not been studied in a systematic way. "The sociolinguistic reality of these perceptions has yet to be explored". Many variations in dialects correspond or reflect the values of particular identities of a community.

Assistive Technology for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing is technology built to assist those who are deaf or suffer from hearing loss. Examples of such technology include hearing aids, video relay services, tactile devices, alerting devices and technology for supporting communication.

Language deprivation in deaf and hard-of-hearing children is a delay in language development that occurs when sufficient exposure to language, spoken or signed, is not provided in the first few years of a deaf or hard of hearing child's life, often called the critical or sensitive period. Early intervention, parental involvement, and other resources all work to prevent language deprivation. Children who experience limited access to language—spoken or signed—may not develop the necessary skills to successfully assimilate into the academic learning environment. There are various educational approaches for teaching deaf and hard of hearing individuals. Decisions about language instruction is dependent upon a number of factors including extent of hearing loss, availability of programs, and family dynamics.

Deaf mental health care is the providing of counseling, therapy, and other psychiatric services to people who are deaf and hard of hearing in ways that are culturally aware and linguistically accessible. This term also covers research, training, and services in ways that improve mental health for deaf people. These services consider those with a variety of hearing levels and experiences with deafness focusing on their psychological well-being. The National Association of the Deaf has identified that specialized services and knowledge of the Deaf increases successful mental health services to this population. States such as North Carolina, South Carolina, and Alabama have specialized Deaf mental health services. The Alabama Department of Mental Health has established an office of Deaf services to serve the more than 39,000 deaf and hard of hearing person who will require mental health services.

People with extreme hearing loss may communicate through sign languages. Sign languages convey meaning through manual communication and body language instead of acoustically conveyed sound patterns. This involves the simultaneous combination of hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to express a speaker's thoughts. "Sign languages are based on the idea that vision is the most useful tool a deaf person has to communicate and receive information".

Protactile is a language used by deafblind people using tactile channels. Unlike other sign languages, which are heavily reliant on visual information, protactile is oriented towards touch and is practiced on the body. Protactile communication originated out of communications by DeafBlind people in Seattle in 2007 and incorporates signs from American Sign Language. Protactile is an emerging system of communication in the United States, with users relying on shared principles such as contact space, tactile imagery, and reciprocity.

In Ireland, 8% of adults are affected by deafness or severe hearing loss. In other words, 300,000 Irish require supports due to their hearing loss.

The Windward Islands are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea that include Dominica, Martinique, Barbados, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, and Grenada. A variety of cultures, beliefs, languages, and views of deafness exist on the islands.

There is limited information on the extent of Deafness in Haiti, due mainly to the lack of census data. Haiti's poor infrastructure makes it almost impossible to obtain accurate information on many health related issues, not just the hearing impaired. In 2003, the number of deaf people in Haiti was estimated at 72,000, based on a survey provided by the World Health Organization.