Skepticism, also spelled scepticism in British English, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the person doubts that these claims are accurate. In such cases, skeptics normally recommend not disbelief but suspension of belief, i.e. maintaining a neutral attitude that neither affirms nor denies the claim. This attitude is often motivated by the impression that the available evidence is insufficient to support the claim. Formally, skepticism is a topic of interest in philosophy, particularly epistemology.

Pyrrho of Elis, born in Elis, Greece, was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek skeptic philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism.

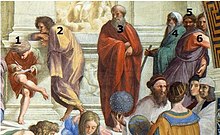

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric and aesthetics. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and later evolved into Roman philosophy.

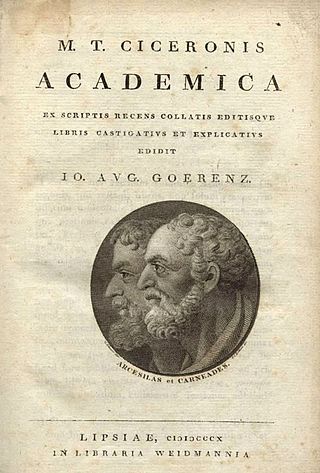

Arcesilaus was a Greek Hellenistic philosopher. He was the founder of Academic Skepticism and what is variously called the Second or Middle or New Academy – the phase of the Platonic Academy in which it embraced philosophical skepticism.

Aenesidemus was a 1st-century BC Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher from Knossos who revived the doctrines of Pyrrho and introduced ten skeptical "modes" (tropai) for the suspension of judgment. He broke with the Academic Skepticism that was predominant in his time, synthesizing the teachings of Heraclitus and Timon of Phlius with philosophical skepticism. Although his primary work, the Pyrrhonian Discourses, has been lost, an outline of the work survives from the later Byzantine empire, and the description of the modes has been preserved by a few ancient sources.

Sextus Empiricus was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician with Roman citizenship. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman Pyrrhonism, and because of the arguments they contain against the other Hellenistic philosophies, they are also a major source of information about those philosophies.

Philosophical skepticism is a family of philosophical views that question the possibility of knowledge. It differs from other forms of skepticism in that it even rejects very plausible knowledge claims that belong to basic common sense. Philosophical skeptics are often classified into two general categories: Those who deny all possibility of knowledge, and those who advocate for the suspension of judgment due to the inadequacy of evidence. This distinction is modeled after the differences between the Academic skeptics and the Pyrrhonian skeptics in ancient Greek philosophy. In the latter sense, skepticism is understood as a way of life that helps the practitioner achieve inner peace. Some types of philosophical skepticism reject all forms of knowledge while others limit this rejection to certain fields, for example, knowledge about moral doctrines or about the external world. Some theorists criticize philosophical skepticism based on the claim that it is a self-refuting idea since its proponents seem to claim to know that there is no knowledge. Other objections focus on its implausibility and distance from regular life.

Eclecticism is a conceptual approach that does not hold rigidly to a single paradigm or set of assumptions, but instead draws upon multiple theories, styles, or ideas to gain complementary insights into a subject, or applies different theories in particular cases. However, this is often without conventions or rules dictating how or which theories were combined.

Carneades was a Greek philosopher, perhaps the most prominent head of the Skeptical Academy in ancient Greece. He was born in Cyrene. By the year 159 BC, he had begun to attack many previous dogmatic doctrines, especially Stoicism and even the Epicureans, whom previous skeptics had spared.

Philo of Larissa was a Greek philosopher. It is very probable that his actual name was Philio - with a second iota. He was a pupil of Clitomachus, whom he succeeded as head of the Academy. During the Mithridatic wars which would see the destruction of the Academy, he travelled to Rome where Cicero heard him lecture. None of his writings survive. He was an Academic sceptic, like Clitomachus and Carneades before him, but he offered a more moderate view of skepticism than that of his teachers, permitting provisional beliefs without certainty.

Timon of Phlius was an Ancient Greek philosopher from the Hellenistic period, who was the student of Pyrrho. Unlike Pyrrho, who wrote nothing, Timon wrote satirical philosophical poetry called Silloi (Σίλλοι) as well as a number of prose writings. These have been lost, but the fragments quoted in later authors allow a rough outline of his philosophy to be reconstructed.

Pyrrhonism is an Ancient Greek school of philosophical skepticism which rejects dogma and advocates the suspension of judgement over the truth of all beliefs. It was founded by Aenesidemus in the first century BCE, and said to have been inspired by the teachings of Pyrrho and Timon of Phlius in the fourth century BCE. Pyrrhonism is best known today through the surviving works of Sextus Empiricus, writing in the late second century or early third century CE. The publication of Sextus' works in the Renaissance ignited a revival of interest in Skepticism and played a major role in Reformation thought and the development of early modern philosophy.

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC – when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy – until the development of neoplatonism under Plotinus in the 3rd century. Middle Platonism absorbed many doctrines from the rival Peripatetic and Stoic schools. The pre-eminent philosopher in this period, Plutarch, defended the freedom of the will and the immortality of the soul. He sought to show that God, in creating the world, had transformed matter, as the receptacle of evil, into the divine soul of the world, where it continued to operate as the source of all evil. God is a transcendent being, who operates through divine intermediaries, which are the gods and daemons of popular religion. Numenius of Apamea combined Platonism with neopythagoreanism and other eastern philosophies, in a move which would prefigure the development of neoplatonism.

In Hellenistic philosophy, epoché is suspension of judgment but also "withholding of assent".

Agrippa was a Pyrrhonist philosopher who probably lived towards the end of the 1st century CE. He is regarded as the author of "The Five Tropes of Agrippa", which are purported to establish the necessity of suspending judgment (epoché). Agrippa's arguments form the basis of the Agrippan trilemma.

Antiochus of Ascalon was an 1st-century BC Platonism philosopher who rejected skepticism and blended Stoic doctrines with Platonism as the first philosopher in the tradition of Middle Platonism.

The Academy, variously known as Plato's Academy, the Platonic Academy, and the Academic School, was founded at Athens by Plato circa 387 BC. Aristotle studied there for twenty years before founding his own school, the Lyceum. The Academy persisted throughout the Hellenistic period as a skeptical school, until coming to an end after the death of Philo of Larissa in 83 BC. The Platonic Academy was destroyed by the Roman dictator Sulla in 86 BC.

Hellenistic philosophy is Ancient Greek philosophy corresponding to the Hellenistic period in Ancient Greece, from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC to the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. The dominant schools of this period were the Stoics, the Epicureans and the Skeptics.

This page is a list of topics in ancient philosophy.

The Academica is work in a fragmentary state written by the Academic Skeptic philosopher, Cicero, published in two editions. The first edition is referred to as the Academica Priora. It was released in May 45 BCE and comprised two books, known as the Catulus and the Lucullus. The Catulus has been lost. Cicero subsequently extensively revised and expanded the work, releasing a second edition comprising four books. Except for part of Book 1 and 36 fragments, all of the second edition has been lost. The second edition is referred to as Academica Posteriora or Academici Libri or Varro.