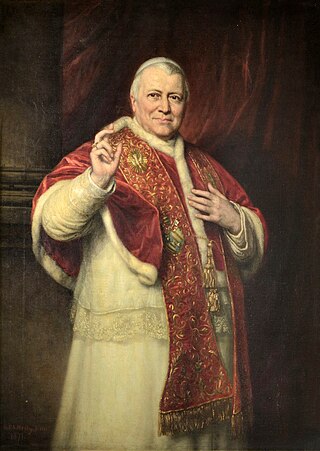

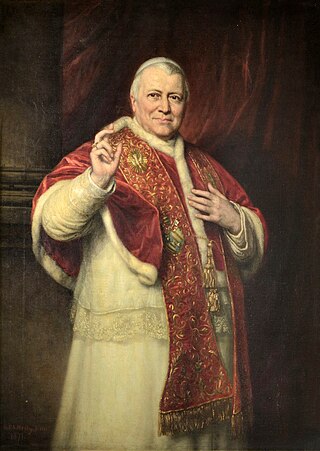

The Immaculate Conception is the belief that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception. It is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Debated by medieval theologians, it was not defined as a dogma until 1854, by Pope Pius IX in the papal bull Ineffabilis Deus. While the Immaculate Conception asserts Mary's freedom from original sin, the Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563, had previously affirmed her freedom from personal sin.

Pyrrho of Elis, born in Elis, Greece, was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek skeptic philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism.

Ijtihad is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a legal question. It is contrasted with taqlid. According to classical Sunni theory, ijtihad requires expertise in the Arabic language, theology, revealed texts, and principles of jurisprudence, and is not employed where authentic and authoritative texts are considered unambiguous with regard to the question, or where there is an existing scholarly consensus (ijma). Ijtihad is considered to be a religious duty for those qualified to perform it. An Islamic scholar who is qualified to perform ijtihad is called as a "mujtahid".

In religion, heterodoxy means "any opinions or doctrines at variance with an official or orthodox position".

Orthodoxy is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Christian theology:

The magisterium of the Catholic Church is the church's authority or office to give authentic interpretation of the word of God, "whether in its written form or in the form of Tradition". According to the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church, the task of interpretation is vested uniquely in the Pope and the bishops, though the concept has a complex history of development. Scripture and Tradition "make up a single sacred deposit of the Word of God, which is entrusted to the Church", and the magisterium is not independent of this, since "all that it proposes for belief as being divinely revealed is derived from this single deposit of faith".

Pyrrhonism is an Ancient Greek school of philosophical skepticism which rejects dogma and advocates the suspension of judgement over the truth of all beliefs. It was founded by Aenesidemus in the first century BCE, and said to have been inspired by the teachings of Pyrrho and Timon of Phlius in the fourth century BCE. Pyrrhonism is best known today through the surviving works of Sextus Empiricus, writing in the late second century or early third century CE. The publication of Sextus' works in the Renaissance ignited a revival of interest in Skepticism and played a major role in Reformation thought and the development of early modern philosophy.

The infallibility of the Church is the belief that the Holy Spirit preserves the Christian Church from errors that would contradict its essential doctrines. It is related to, but not the same as, indefectibility, that is, "she remains and will remain the Institution of Salvation, founded by Christ, until the end of the world." The doctrine of infallibility is premised on the authority Jesus granted to the apostles to "bind and loose" and in particular the promises to Peter in regard to papal infallibility.

Taqlid is an Islamic term denoting the conformity of one person to the teaching of another. The person who performs taqlid is termed muqallid. The definite meaning of the term varies depending on context and age. Classical usage of the term differs between Sunni Islam and Shia Islam. Sunni Islamic usage designates the unjustified conformity of one person to the teaching of another, rather than the justified conformity of a layperson to the teaching of mujtahid. Shia Islamic usage designates the general conformity of non-mujtahid to the teaching of mujtahid, and there is no negative connotation. The discrepancy corresponds to differing views on Shia views on the Imamate and Sunni imams.

Dogmatic theology, also called dogmatics, is the part of theology dealing with the theoretical truths of faith concerning God and God's works, especially the official theology recognized by an organized Church body, such as the Roman Catholic Church, Dutch Reformed Church, etc. At times, apologetics or fundamental theology is called "general dogmatic theology", dogmatic theology proper being distinguished from it as "special dogmatic theology". In present-day use, however, apologetics is no longer treated as part of dogmatic theology but has attained the rank of an independent science, being generally regarded as the introduction to and foundation of dogmatic theology.

The idea of purgatory has roots that date back into antiquity. A sort of proto-purgatory called the "celestial Hades" appears in the writings of Plato and Heraclides Ponticus and in many other pagan writers. This concept is distinguished from the Hades of the underworld described in the works of Homer and Hesiod. In contrast, the celestial Hades was understood as an intermediary place where souls spent an undetermined time after death before either moving on to a higher level of existence or being reincarnated back on earth. Its exact location varied from author to author. Heraclides of Pontus thought it was in the Milky Way; the Academicians, the Stoics, Cicero, Virgil, Plutarch, the Hermetical writings situated it between the Moon and the Earth or around the Moon; while Numenius and the Latin Neoplatonists thought it was located between the sphere of the fixed stars and the Earth.

A dogma of the Catholic Church is defined as "a truth revealed by God, which the magisterium of the Church declared as binding". The Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

The Church's Magisterium asserts that it exercises the authority it holds from Christ to the fullest extent when it defines dogmas, that is, when it proposes, in a form obliging Catholics to an irrevocable adherence of faith, truths contained in divine Revelation or also when it proposes, in a definitive way, truths having a necessary connection with these.

Catholic dogmatic theology can be defined as "a special branch of theology, the object of which is to present a scientific and connected view of the accepted doctrines of the Christian faith."

Twelver Shīʿism, also known as Imāmiyya, is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term Twelver refers to its adherents' belief in twelve divinely ordained leaders, known as the Twelve Imams, and their belief that the last Imam, Imam al-Mahdi, lives in Occultation and will reappear as the promised Mahdi.

The theological notes designate a classification of certainty of beliefs in Catholic theology.

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks ex cathedra is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apostolic Church and handed down in Scripture and tradition". It does not mean that the pope cannot sin or otherwise err in some capacity, though he is prevented by the assistance of the Holy Spirit from issuing heretical teaching even in his non-infallible Magisterium, as a corollary of indefectibility. This doctrine, defined dogmatically at the First Vatican Council of 1869–1870 in the document Pastor aeternus, is claimed to have existed in medieval theology and to have been the majority opinion at the time of the Counter-Reformation.

Academic skepticism refers to the skeptical period of the Academy dating from around 266 BCE, when Arcesilaus became scholarch, until around 90 BCE, when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected skepticism, although individual philosophers, such as Favorinus and his teacher Plutarch, continued to defend skepticism after this date. Unlike the existing school of skepticism, the Pyrrhonists, they maintained that knowledge of things is impossible. Ideas or notions are never true; nevertheless, there are degrees of plausibility, and hence degrees of belief, which allow one to act. The school was characterized by its attacks on the Stoics, particularly their dogma that convincing impressions led to true knowledge. The most important Academics were Arcesilaus, Carneades, and Philo of Larissa. The most extensive ancient source of information about Academic skepticism is Academica, written by the Academic skeptic philosopher Cicero.

The Latin Church is the largest autonomous particular church within the Catholic Church, whose members constitute the vast majority of the 1.3 billion Catholics. The Latin Church is one of 24 churches sui iuris in full communion with the pope; the other 23 are collectively referred to as the Eastern Catholic Churches, and have approximately 18 million members combined.