The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family—English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch, and Spanish—have expanded through colonialism in the modern period and are now spoken across several continents. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, of which there are eight groups with languages still alive today: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic/Romance; and another nine subdivisions that are now extinct.

The Proto-Indo-Europeans are a hypothetical prehistoric ethnolinguistic group of Eurasia who spoke Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family.

Andrew Colin Renfrew, Baron Renfrew of Kaimsthorn, is a British archaeologist, paleolinguist and Conservative peer noted for his work on radiocarbon dating, the prehistory of languages, archaeogenetics, neuroarchaeology, and the prevention of looting at archaeological sites.

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages.

Old Europe is a term coined by the Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas to describe what she perceived as a relatively homogeneous pre-Indo-European Neolithic and Copper Age culture or civilisation in Southeast Europe, centred in the Lower Danube Valley. Old Europe is also referred to in some literature as the Danube civilisation.

Proto-Indo-European society is the reconstructed culture of Proto-Indo-Europeans, the ancient speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, ancestor of all modern Indo-European languages.

The Kurgan hypothesis is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia. It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). The term is derived from the Turkic word kurgan (курга́н), meaning tumulus or burial mound.

In Indo-European linguistics, the term Indo-Hittite refers to Edgar Howard Sturtevant's 1926 hypothesis that the Anatolian languages may have split off a Pre-Proto-Indo-European language considerably earlier than the separation of the remaining Indo-European languages. The term may be somewhat confusing, as the prefix Indo- does not refer to the Indo-Aryan branch in particular, but is iconic for Indo-European, and the -Hittite part refers to the Anatolian language family as a whole.

Graeco-Aryan, or Graeco-Armeno-Aryan, is a hypothetical clade within the Indo-European family that would be the ancestor of Hellenic, Armenian, and the Indo-Iranian languages, which spans Southern Europe, Armenian highlands and Southern Asian regions of Eurasia.

The Sredny Stog culture is a pre-Kurgan archaeological culture from the 5th–4th millennia BC. It is named after the Dnieper river islet of today's Serednii Stih, Ukraine, where it was first located.

The Anatolians were Indo-European-speaking peoples of the Anatolian Peninsula in present-day Turkey, identified by their use of the Anatolian languages. These peoples were among the oldest Indo-European ethnolinguistic groups and one of the most archaic, because Anatolians were among the first Indo-European peoples to separate from the Proto-Indo-European community that gave origin to the individual Indo-European peoples.

The Pre-Greek substrate consists of the unknown pre-Indo-European language(s) spoken in prehistoric Greece before the advent of the Proto-Greek language in the Greek peninsula during the Bronze Age. It is possible that Greek acquired approximately 1,000 words from such a language or group of languages, because some of its vocabulary cannot be satisfactorily explained as deriving from Proto-Greek and a Proto-Indo-European reconstruction is almost certainly impossible for such terms.

The Armenian hypothesis, also known as the Near Eastern model, is a theory of the Proto-Indo-European homeland, initially proposed by linguists Tamaz V. Gamkrelidze and Vyacheslav Ivanov in the early 1980s, which suggests that the Proto-Indo-European language was spoken during the 5th–4th millennia BC in "eastern Anatolia, the southern Caucasus, and northern Mesopotamia".

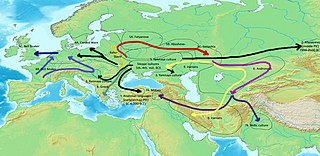

The Proto-Indo-European homeland was the prehistoric linguistic homeland of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). From this region, its speakers migrated east and west, and went on to form the proto-communities of the different branches of the Indo-European language family.

The Neolithic creolisation hypothesis, first put forward by Marek Zvelebil in 1995, situates the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat in northern Europe in Neolithic times at the Baltic coast, proposing that migrating Neolithic farmers mixed with indigenous Mesolithic hunter-gatherer communities, resulting in the genesis of the Indo-European language family.

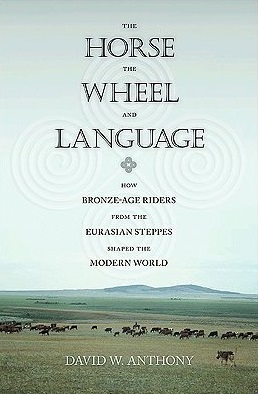

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World is a 2007 book by the anthropologist David W. Anthony, in which the author describes his "revised Kurgan theory." He explores the origins and spread of the Indo-European languages from the Pontic–Caspian steppe throughout Western Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia. He shows how the domesticated horse and the invention of the wheel mobilized the steppe herding societies in the Eurasian Steppe, and combined with the introduction of bronze technology and new social structures of patron-client relationships gave an advantage to the Indo-European societies. The book won the Society for American Archaeology's 2010 Book Award.

The Indo-European migrations are hypothesized migrations of Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) speakers, and subsequent migrations of people speaking derived Indo-European languages, which took place approx. 4000 to 1000 BCE, potentially explaining how these languages came to be spoken across a large area of Eurasia, spanning from the Indian subcontinent and Iranian plateau to Atlantic Europe.

The Paleo-European languages, or Old European languages, are the mostly unknown languages that were spoken in Europe prior to the spread of the Indo-European and Uralic families caused by the Bronze Age invasion from the Eurasian steppe of pastoralists whose descendant languages dominate the continent today. Today, the vast majority of European populations speak Indo-European languages, but until the Bronze Age, it was the opposite, with Paleo-European languages of non-Indo-European affiliation dominating the linguistic landscape of Europe.

The farming/language dispersal hypothesis proposes that many of the largest language families in the world dispersed along with the expansion of agriculture. This hypothesis was proposed by archaeologists Peter Bellwood and Colin Renfrew. It has been widely debated and archaeologists, linguists, and geneticists often disagree with all or only parts of the hypothesis.