The Diablo Canyon Power Plant is a nuclear power plant near Avila Beach in San Luis Obispo County, California. Following the permanent shutdown of the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station in 2013, Diablo Canyon is now the only operational nuclear plant in California, as well as the state's largest single power station. It was the subject of controversy and protests during its construction, with nearly two thousand civil disobedience arrests in a two-week period in 1981.

The San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) is a permanently closed nuclear power plant located south of San Clemente, California, on the Pacific coast, in Nuclear Regulatory Commission Region IV. The plant was shut down in 2013 after defects were found in replacement steam generators; it is currently in the process of decommissioning. The 2.2 GW of electricity supply lost when the plant shut down was replaced with 1.8 GW of new natural-gas fired power plants and 250 MW of energy storage projects.

The anti-nuclear movement is a social movement that opposes various nuclear technologies. Some direct action groups, environmental movements, and professional organisations have identified themselves with the movement at the local, national, or international level. Major anti-nuclear groups include Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, Peace Action, Seneca Women's Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice and the Nuclear Information and Resource Service. The initial objective of the movement was nuclear disarmament, though since the late 1960s opposition has included the use of nuclear power. Many anti-nuclear groups oppose both nuclear power and nuclear weapons. The formation of green parties in the 1970s and 1980s was often a direct result of anti-nuclear politics.

In the United States, nuclear power is provided by 92 commercial reactors with a net capacity of 94.7 gigawatts (GW), with 61 pressurized water reactors and 31 boiling water reactors. In 2019, they produced a total of 809.41 terawatt-hours of electricity, which accounted for 20% of the nation's total electric energy generation. In 2018, nuclear comprised nearly 50 percent of US emission-free energy generation.

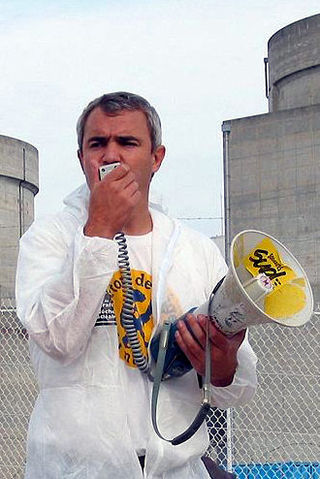

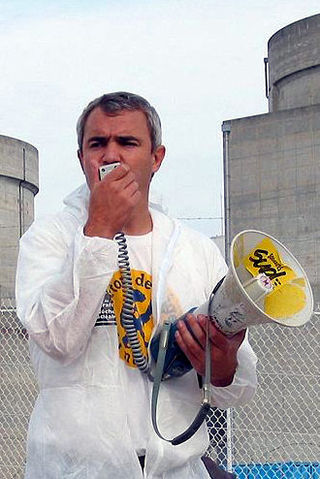

The Abalone Alliance (1977–1985) was a nonviolent civil disobedience group formed to shut down the Pacific Gas and Electric Company's Diablo Canyon Power Plant near San Luis Obispo on the central California coast in the United States. They modeled their affinity group-based organizational structure after the Clamshell Alliance which was then protesting the Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant in coastal New Hampshire. The group of activists took the name "Abalone Alliance" referring to the tens of thousands of wild California Red Abalone that were killed in 1974 in Diablo Cove when the unit's plumbing had its first hot flush.

Nuclear history of the United States describes the history of nuclear affairs in the United States whether civilian or military.

The anti-nuclear movement in the United States consists of more than 80 anti-nuclear groups that oppose nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and/or uranium mining. These have included the Abalone Alliance, Clamshell Alliance, Committee for Nuclear Responsibility, Nevada Desert Experience, Nuclear Information and Resource Service, Physicians for Social Responsibility, Plowshares Movement, United Steelworkers of America (USWA) District 31, Women Strike for Peace, Nukewatch, and Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Some fringe aspects of the anti-nuclear movement have delayed construction or halted commitments to build some new nuclear plants, and have pressured the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to enforce and strengthen the safety regulations for nuclear power plants. Most groups in the movement focus on nuclear weapons.

The anti-nuclear movement in Germany has a long history dating back to the early 1970s when large demonstrations prevented the construction of a nuclear plant at Wyhl. The Wyhl protests were an example of a local community challenging the nuclear industry through a strategy of direct action and civil disobedience. Police were accused of using unnecessarily violent means. Anti-nuclear success at Wyhl inspired nuclear opposition throughout West Germany, in other parts of Europe, and in North America. A few years later protests raised against the NATO Double-Track Decision in West Germany and were followed by the foundation of the Green party.

In the 1970s, an anti-nuclear movement in France, consisting of citizens' groups and political action committees, emerged. Between 1975 and 1977, some 175,000 people protested against nuclear power in ten demonstrations.

More than 80 anti-nuclear groups are operating, or have operated, in the United States. These include Abalone Alliance, Clamshell Alliance, Greenpeace USA, Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, Musicians United for Safe Energy, Nevada Desert Experience, Nuclear Control Institute, Nuclear Information and Resource Service, Public Citizen Energy Program, Shad Alliance, and the Sierra Club. These are direct action, environmental, health, and public interest organizations who oppose nuclear weapons and/or nuclear power. In 1992, the chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission said that "his agency had been pushed in the right direction on safety issues because of the pleas and protests of nuclear watchdog groups".

Anti-nuclear protests began on a small scale in the U.S. as early as 1946 in response to Operation Crossroads. Large scale anti-nuclear protests first emerged in the mid-1950s in Japan in the wake of the March 1954 Lucky Dragon Incident. August 1955 saw the first meeting of the World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, which had around 3,000 participants from Japan and other nations. Protests began in Britain in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March, organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, took place in 1958. In 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. In 1964, Peace Marches in several Australian capital cities featured "Ban the Bomb" placards.

Conservation Fallout: Nuclear Protest at Diablo Canyon is a 2006 book by John Wills.

The Sundesert Nuclear Power Plant was a proposed California nuclear power station, formally submitted in 1976. Facing firm opposition from the state's Governor Jerry Brown and denied a permit by a state agency, plans for the construction of the power facility were rejected in 1978 after 100 million dollars had been spent towards its construction. The Sundesert proposal was the last major attempt to build a nuclear plant in California.

The Bodega Bay Nuclear Power Plant was a proposed Northern California nuclear power facility that was stopped by local activism in the 1960s and never built. The foundations, located 2 miles (3.2 km) west of the active San Andreas Fault, were being dug at the time the plant was cancelled. The action has been termed "the birth of the anti-nuclear movement."

The nuclear energy policy of the United States began in 1954 and continued with the ongoing building of nuclear power plants, the enactment of numerous pieces of legislation such as the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, and the implementation of countless policies which have guided the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Department of Energy in the regulation and growth of nuclear energy companies. This includes, but is not limited to, regulations of nuclear facilities, waste storage, decommissioning of weapons-grade materials, uranium mining, and funding for nuclear companies, along with an increase in power plant building. Both legislation and bureaucratic regulations of nuclear energy in the United States have been shaped by scientific research, private industries' wishes, and public opinion, which has shifted over time and as a result of different nuclear disasters.

San Luis Obispo Mothers for Peace (SLOMFP) is a participant in the anti-nuclear movement in California which is depicted in the anti-nuclear documentary film Dark Circle during the early years of protest opposing the Diablo Canyon Power Plant (DCPP). In Dark Circle, Mothers for Peace takes credit for delays which prevented the plant from going online prior to the discovery of the errors.

Alliance for Nuclear Responsibility is a non-profit, anti-nuclear, public interest organization founded in 2005, and based in San Luis Obispo, California. It is focused on public citizen activism and public participation with regard to the Diablo Canyon Power Plant, also known as the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant. The focus of the group is primarily on using leverage at the level of state agencies such as the California Public Utilities Commission. Concurrent jurisdiction of their concern also includes the California Coastal Commission, which certifies compliance of all action within the coastal zone which thus includes the plant. Their posture is primarily oppositional. Other venues for activism include the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, California Energy Commission, Regional Water Quality Control Board, SLO County, the California legislature, the office of the state attorney general, and the US Congress, of which they are in the 23rd District.

Diablo Canyon (Nuclear) Power Plant, located in San Luis Obispo County California, was originally designed to withstand a 6.75 magnitude earthquake from four faults, including the nearby San Andreas and Hosgri faults, but was later upgraded to withstand a 7.5 magnitude quake. It has redundant seismic monitoring and a safety system designed to shut it down promptly in the event of significant ground motion.

Anti-nuclear protests in the United States have occurred since the development of nuclear power plants in the United States. Examples include Clamshell Alliance protests at Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant, Abalone Alliance protests at Diablo Canyon Power Plant, and those following the Three Mile Island accident in 1979.