Lycia was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is today the provinces of Antalya and Muğla in Turkey as well some inland parts of Burdur Province. The state was known to history from the Late Bronze Age records of ancient Egypt and the Hittite Empire. Lycia was populated by speakers of the Luwian language group. Written records began to be inscribed in stone in the Lycian language after Lycia's involuntary incorporation into the Achaemenid Empire in the Iron Age. At that time (546 BC) the Luwian speakers were displaced as Lycia received an influx of Persian speakers. Ancient sources seem to indicate that an older name of the region was Alope.

Myra was a Lycian, then ancient Greek, then Greco-Roman, then Byzantine Greek, then Ottoman town in Lycia, which became the small Turkish town of Kale, renamed Demre in 2005, in the present-day Antalya Province of Turkey. In 1923, its Greek inhabitants had been required to leave by the population exchange between Greece and Turkey, at which time its church was finally abandoned. It was founded on the river Myros, in the fertile alluvial plain between Alaca Dağ, the Massikytos range and the Aegean Sea.

Xanthos or Xanthus, also referred to by scholars as Arna, its Lycian name, was an ancient city near the present-day village of Kınık, in Antalya Province, Turkey. The ruins are located on a hill on the left bank of the River Xanthos. The number and quality of the surviving tombs at Xanthos are a notable feature of the site, which, together with nearby Letoon, was declared to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988.

The Lycian Way is a marked long-distance hiking trail in southwestern Turkey around part of the coast of ancient Lycia. It is approximately 520 km (320 mi) in length and stretches from Hisarönü (Ovacık), near Fethiye, to Aşağı Karaman in Konyaaltı, about 20 km (12 mi) from Antalya. It is waymarked with red and white stripes of the GR footpath convention.

Letoon or Letoum in the Fethiye district of Muğla Province, Turkey, was a sanctuary of Leto located 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) south of the ancient city of Xanthos, to which it was closely associated, and along the Xanthos River. It was one of the most important religious centres in the region though never a fully-occupied settlement.

Pinara was a large city of ancient Lycia at the foot of Mount Cragus, and not far from the western bank of the River Xanthos, homonymous with the ancient city of Xanthos.

Kaş is a small fishing, diving, yachting and tourist town, and a municipality and district of Antalya Province, Turkey. Its area is 1,750 km2, and its population is 62,866 (2022). It is 168 km west of the city of Antalya. As a tourist resort, it is relatively unspoiled.

Sidyma, was a town of ancient Lycia, at what is now the small village of Dudurga Asari in Muğla Province, Turkey. It lies on the southern slope of Mount Cragus, to the north-west of the mouth of the Xanthus.

Rhodiapolis, also known as Rhodia (Ῥοδία) and Rhodiopolis (Ῥοδιόπολις), was a city in ancient Lycia. Today it is located on a hill northwest of the modern town Kumluca in Antalya Province, Turkey.

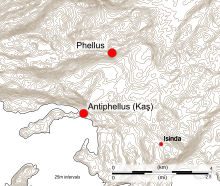

Phellus is the site of an ancient Lycian city, situated in a mountainous area near Çukurbağ in Antalya Province,Turkey. The city was mentioned by the Greek geographer and philosopher Strabo in his Geographica. Antiphellusserved as the city's port.

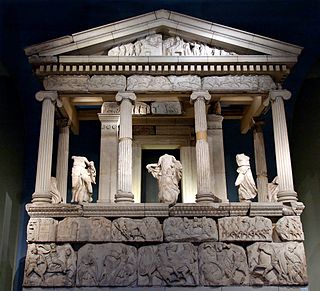

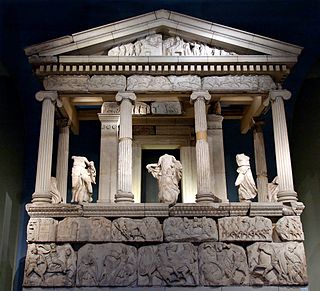

The Nereid Monument is a sculptured tomb from Xanthos in Lycia, close to present-day Fethiye in Mugla Province, Turkey. It took the form of a Greek temple on top of a base decorated with sculpted friezes, and is thought to have been built in the early fourth century BC as a tomb for Arbinas, the Xanthian dynast who ruled western Lycia under the Achaemenid Empire.

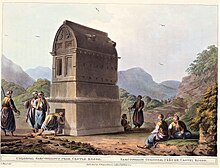

The Tomb of Payava is a Lycian tall rectangular free-standing barrel-vaulted stone sarcophagus, and one of the most famous tombs of Xanthos. It was built in the Achaemenid Persian Empire, for Payava, who was probably the ruler of Xanthos, Lycia at the time, in around 360 BC. The tomb was discovered in 1838 and brought to England in 1844 by the explorer Sir Charles Fellows. He described it as a 'Gothic-formed Horse Tomb'. According to Melanie Michailidis, though bearing a "Greek appearance", the Tomb of Payava, the Harpy Tomb and the Nereid Monument were built according to the main Zoroastrian criteria "by being composed of thick stone, raised on plinths off the ground, and having single windowless chambers".

Trebenna (Τρεβέννα) or Trabenna (Τραβέννα) was a city in ancient Lycia, at the border with Pamphylia, and at times ascribed to that latter region. Its ruins are located east of the modern town Çağlarca in the Konyaaltı district of Antalya Province, Turkey. The site lies 22 km to the west of Antalya.

Idebessos or Idebessus, also known as Edebessus or Edebessos or, was an ancient city in Lycia. It was located at the foot of the Bey Mountains to the west of the Alakır river valley. Today its ruins are found a short distance to the west of the small village of Kozağacı in the Kumluca district of Antalya Province, Turkey. The site, 21 kilometres north-northwest of Kumluca, is overgrown with forest and hard to reach.

Apollonia was a city in ancient Lycia. Its ruins are located near Kiliçli (Sıçak), a small village in the Kaş district of Antalya Province, Turkey.

Cyaneae, also spelled Kyaneai or Cyanae, was a town of ancient Lycia, or perhaps three towns known collectively by the name. Leake observes that in some copies of Pliny it is written Cyane; in Hierocles and the Notitiae Episcopatuum it is Cyaneae.

Nisa, also Nyssa (Νύσσα) or Nysa (Νύσα) or Neisa (Νείσα), was a town in ancient Lycia near the source of the River Xanthus.

Xanthos, also called Xanthus, was a chief city state of the Lycians, an indigenous people of southwestern Anatolia. Many of the tombs at Xanthos are pillar tombs, formed of a stone burial chamber on top of a large stone pillar. The body would be placed in the top of the stone structure, elevating it above the landscape. The tombs are for men who ruled in a Lycian dynasty from the mid-6th century to the mid-4th century BCE and help to show the continuity of their power in the region. Not only do the tombs serve as a form of monumentalization to preserve the memory of the rulers, but they also reveal the adoption of Greek style of decoration.

Isinda was a town of ancient Lycia. Isinda was part of a sympoliteia with Aperlae, Apollonia and Simena.