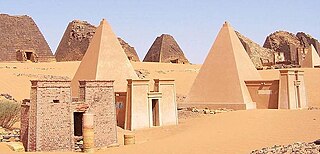

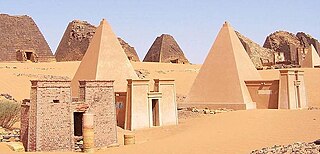

Meroë was an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, approximately 200 km north-east of Khartoum. Near the site is a group of villages called Bagrawiyah. This city was the capital of the Kingdom of Kush for several centuries from around 590 BC, until its collapse in the 4th century AD. The Kushitic Kingdom of Meroë gave its name to the "Island of Meroë", which was the modern region of Butana, a region bounded by the Nile, the Atbarah and the Blue Nile.

Natakamani, also called Aqrakamani, was a king of Kush who reigned from Meroë in the middle of the 1st century CE. He ruled as co-regent together with his mother Amanitore. Natakamani is the best attested ruler of the Meroitic period. He and Amanitore may have been contemporaries of the Roman emperor Nero.

Amanishakheto was a queen regnant (kandake) of Kush who reigned in the early 1st century AD. In Meroitic hieroglyphs her name is written "Amanikasheto". In Meroitic cursive she is referred to as Amaniskheto qor kd(ke) which means Amanishakheto, Qore and Kandake.

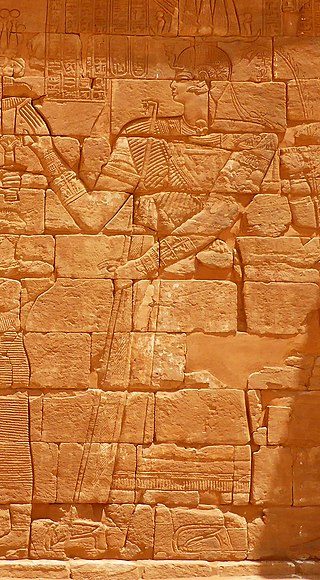

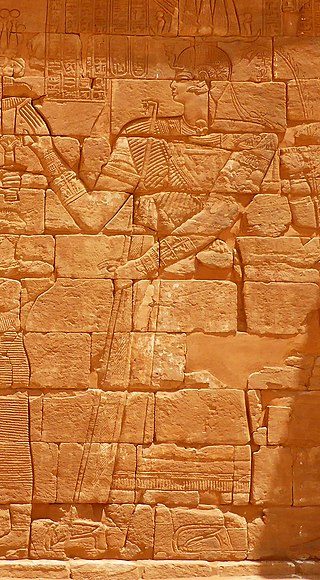

Shanakdakhete, also spelled Shanakdakheto or Sanakadakhete, was a queen regnant of the Kingdom of Kush, ruling from Meroë in the early first century AD. Shanakdakhete is poorly attested, though is known to have constructed a temple in Naqa.

The Butana, historically called the Island of Meroë, is the region between the Atbara and the Nile in the Sudan. South of Khartoum it is bordered by the Blue Nile and in the east by Lake Tana in Ethiopia. It should not be confused with the Gezira, the region west of the Blue Nile and east of the White Nile.

The National Museum of Sudan or Sudan National Museum, abbreviated SNM, is a two-story building, constructed in 1955 and established as national museum in 1971.

Amanitore, also spelled Amanitere or Amanitare, was a queen regnant of the Kingdom of Kush, ruling from Meroë in the middle of the 1st century CE. She ruled together with her son, Natakamani. The co-reign of Amanitore and Natakamani is a very well attested period and appears to have been a prosperous time. They may have been contemporaries of the Roman emperor Nero.

Nubia is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, or more strictly, Al Dabbah. It was the seat of one of the earliest civilizations of ancient Africa, the Kerma culture, which lasted from around 2500 BC until its conquest by the New Kingdom of Egypt under Pharaoh Thutmose I around 1500 BC, whose heirs ruled most of Nubia for the next 400 years. Nubia was home to several empires, most prominently the Kingdom of Kush, which conquered Egypt in the eighth century BC during the reign of Piye and ruled the country as its 25th Dynasty.

The Kingdom of Kush, also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

Louis Vico Žabkar was an American Egyptologist who published a number of academic works and who participated in the 1960s in the UNESCO campaign to salvage the monuments threatened by the building of the Aswan Dam.

Naqa or Naga'a is a ruined ancient city of the Kushitic Kingdom of Meroë in modern-day Sudan. The ancient city lies about 170 km (110 mi) north-east of Khartoum, and about 50 km (31 mi) east of the Nile River located at approximately MGRS 36QWC290629877. Here smaller wadis meet the Wadi Awateib coming from the center of the Butana plateau region, and further north at Wad ban Naqa from where it joins the Nile. Naqa was only a camel or donkey's journey from the Nile, and could serve as a trading station on the way to the east; thus it had strategic importance.

Arqamani was a Kushite King of Meroë dating from the late 3rd to early 2nd century BCE.

Musawwarat es-Sufra, also known as Al-Musawarat Al-Sufra, is a large Meroitic temple complex in modern Sudan, dating back to the early Meroitic period of the 3rd century BC. It is located in a large basin surrounded by low sandstone hills in the western Butana, 180 km northeast of Khartoum, 20 km north of Naqa and approximately 25 km south-east of the Nile. With Meroë and Naqa it is known as the Island of Meroe, and was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011. Constructed in sandstone, the main features of the site include the Great Enclosure, the Lion Temple of Apedemak and the Great Reservoir. Most significant is the number of representations of elephants, suggesting that this animal played an important role at Musawwarat es-Sufra.

Arnekhamani was a Nubian king of the Kushite Kingdom in the third century BC. The king is mainly known from his building activity at the Musawwarat es-Sufra temple complex. The main temple complex at this place was built by Arnekhamani, but was never finished. Most likely the king died before completing the temples.

Amesemi is a Kushite protective goddess and wife of Apedemak, the lion-god. She was represented with a crown shaped as a falcon, or with a crescent moon on her head on top of which a falcon was standing. The clothing that Amesemi is seen wearing is a robe that is made from cloth and is worn over her undergarments. She is often seen wearing a short necklace with large beads. She is also depicted holding a second set of hands with her.

Sebiumeker was a major supreme god of procreation and fertility in Nubian mythology who was primarily worshipped in Meroe, Kush, in present-day Sudan. He is sometimes thought of as a guardian of gateways as his statues are sometimes found near doorways. He has many similarities with Atum, but has Nubian characteristics, and is also considered the god of agriculture.

Maloqorebar was an ancient Kushite prince.

Yesebokheamani was the king (qore) of Kush in the late 3rd or early 4th century AD. He seems to have been the king who took control of the Dodecaschoenus after the Roman withdrawal in 298. This enabled him to make a personal visit to the temple of Isis at Philae.

The reign of Amanitore was considered one of the most prosperous times of the Meroitic period. She ruled alongside Natakamani, who was either her husband or her son. The success of the two rulers is evident through their work towards the building, restoration, and expansion of many temples throughout Nubia. The temples that can be accredited to the work of the two include: the Temple of Apedemak, the Amun temple B500 at Napata, the Amun temple at Meroe, the Amun Temples of Naqa and Amara, the Isis temple at Wad ben Naqa, and the Meroitic palace B1500 at Napata.

Talakhidamani was the king of Kush in the mid or late 3rd century AD, perhaps into the 4th century. He is known from two Meroitic inscriptions, one of which commemorates a diplomatic mission he sent to the Roman Empire.