Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who ruled c. 1332 – 1323 BC during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he was likely a son of Akhenaten, thought to be the KV55 mummy. His mother was identified through DNA testing as The Younger Lady buried in KV35; she was a full sister of her husband.

Aten also Aton, Atonu, or Itn was the focus of Atenism, the religious system formally established in ancient Egypt by the late Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. Exact dating for the 18th dynasty is contested, though a general date range places the dynasty in the years 1550 to 1292 B.C.E. The worship of Aten and the coinciding rule of Akhenaten are major identifying characteristics of a period within the 18th dynasty referred to as the Amarna Period.

Akhenaten, also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning c. 1353–1336 or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before the fifth year of his reign, he was known as Amenhotep IV.

Nefertiti was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for their radical overhaul of state religious policy, in which they promoted the earliest known form of monotheism, Atenism, centered on the sun disc and its direct connection to the royal household. With her husband, she reigned at what was arguably the wealthiest period of ancient Egyptian history. After her husband's death, some scholars believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly as the female king known by the throne name, Neferneferuaten and before the ascension of Tutankhamun, although this identification is a matter of ongoing debate. If Nefertiti did rule as Pharaoh, her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.

Tiye was the Great Royal Wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III, mother of pharaoh Akhenaten and grandmother of pharaoh Tutankhamun; her parents were Yuya and Thuya. In 2010, DNA analysis confirmed her as the mummy known as "The Elder Lady" found in the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35) in 1898.

Monolatry is the belief in the existence of many gods, but with the consistent worship of only one deity. The term monolatry was perhaps first used by Julius Wellhausen.

Smenkhkare was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of unknown background who lived and ruled during the Amarna Period of the 18th Dynasty. Smenkhkare was husband to Meritaten, the daughter of his likely co-regent, Akhenaten. Since the Amarna period was subject to a large-scale condemnation of memory by later Pharaohs, very little can be said of Smenkhkare with certainty, and he has hence been subject to immense speculation.

Kiya was one of the wives of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. Little is known about her, and her actions and roles are poorly documented in the historical record, in contrast to those of Akhenaten's 'Great royal wife', Nefertiti. Her unusual name suggests that she may originally have been a Mitanni princess. Surviving evidence demonstrates that Kiya was an important figure at Akhenaten's court during the middle years of his reign, when she had a daughter with him. She disappears from history a few years before her royal husband's death. In previous years, she was thought to be mother of Tutankhamun, but recent DNA evidence suggests this is unlikely.

Ay was the penultimate pharaoh of ancient Egypt's 18th Dynasty. He held the throne of Egypt for a brief four-year period in the late 14th century BC. Prior to his rule, he was a close advisor to two, and perhaps three, other pharaohs of the dynasty. It is speculated that he was the power behind the throne during child ruler Tutankhamun's reign. His prenomenKheperkheperure means "Everlasting are the Manifestations of Ra", while his nomenAy it-netjer reads as "Ay, Father of the God". Records and monuments that can be clearly attributed to Ay are rare, both because his reign was short and because his successor, Horemheb, instigated a campaign of damnatio memoriae against him and the other pharaohs associated with the unpopular Amarna Period.

Meritaten, also spelled Merytaten, Meritaton or Meryetaten, was an ancient Egyptian royal woman of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Her name means "She who is beloved of Aten"; Aten being the sun-deity whom her father, Pharaoh Akhenaten, worshipped. She held several titles, performing official roles for her father and becoming the Great Royal Wife to Pharaoh Smenkhkare, who may have been a brother or son of Akhenaten. Meritaten also may have served as pharaoh in her own right under the name Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten.

Ankhesenamun was a queen who lived during the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. Born Ankhesenpaaten, she was the third of six known daughters of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti. She became the Great Royal Wife of Tutankhamun. The change in her name reflects the changes in ancient Egyptian religion during her lifetime after her father's death. Her youth is well documented in the ancient reliefs and paintings of the reign of her parents.

The Amarna Period was an era of Egyptian history during the later half of the Eighteenth Dynasty when the royal residence of the pharaoh and his queen was shifted to Akhetaten in what is now Amarna. It was marked by the reign of Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten in order to reflect the dramatic change of Egypt's polytheistic religion into one where the sun disc Aten was worshipped over all other gods. The Egyptian pantheon was restored under Akhenaten's successor, Tutankhamun.

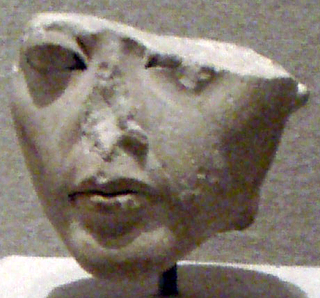

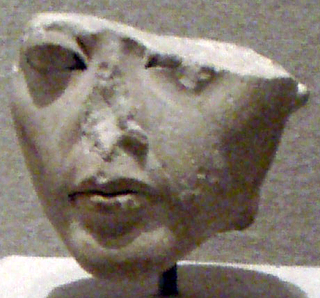

Amarna art, or the Amarna style, is a style adopted in the Amarna Period during and just after the reign of Akhenaten in the late Eighteenth Dynasty, during the New Kingdom. Whereas Ancient Egyptian art was famously slow to change, the Amarna style was a significant and sudden break from its predecessors both in the style of depictions, especially of people, and the subject matter. The artistic shift appears to be related to the king's religious reforms centering on the monotheistic or monolatric worship of the Aten, the disc of the Sun, as giver of life.

Meketaten was the second of six daughters born to the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti. She likely lived between Year 4 and Year 14 of Akhenaten's reign. Although little is known about her, she is frequently depicted with her sisters accompanying her royal parents in the first two-thirds of the Amarna Period.

Neferneferuaten Tasherit or Neferneferuaten the younger was an ancient Egyptian princess of the 18th Dynasty and the fourth daughter of Pharaoh Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti.

Ankhkheperure-Merit-Neferkheperure/Waenre/Aten Neferneferuaten was a name used to refer to a female king who reigned toward the end of the Amarna Period during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Her gender is confirmed by feminine traces occasionally found in the name and by the epithet Akhet-en-hyes, incorporated into one version of her nomen cartouche. She is distinguished from the king Smenkhkare who used the same throne name, Ankhkheperure, by the presence of epithets in both cartouches. She is suggested to have been either Smenkhkare's wife, Meritaten or, his predecessor's widow, Nefertiti. If this person is Nefertiti ruling as sole king, it has been theorized by Egyptologist and archaeologist Zahi Hawass that her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.

Amun was a major ancient Egyptian deity who appears as a member of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. Amun was attested from the Old Kingdom together with his wife Amunet. With the 11th Dynasty, Amun rose to the position of patron deity of Thebes by replacing Montu.

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty spanned the period from 1550/1549 to 1292 BC. This dynasty is also known as the Thutmoside Dynasty) for the four pharaohs named Thutmose.

The Amarna Era includes the reigns of Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Tutankhamun and Ay. The period is named after the capital city established by Akhenaten, son of Amenhotep III. Akhenaten started his reign as Amenhotep IV, but changed his name when he discarded all other religions and declared the Aten or sun disc as the only god. He closed all the temples of the other Gods and removed their names from the monuments. Smenkhkare, then Tutankhamun, succeeded Akhenaten. Discarding Akhenten's religious beliefs, Tutankhamun returned to the traditional gods. He died young and was succeeded by Ay. Many kings did their best to remove all traces of the period from the records. The Amarna art is very distinctive: the royal family was portrayed with extended heads, long necks and narrow chests. They had skinny limbs, but heavy hips and thighs, with a marked stomach.

A God Against the Gods is a 1976 historical novel by political novelist Allen Drury, which chronicles ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten's attempt to establish a new religion in Egypt. It is told in a series of monologues by the various characters.