Ruthenian and Ruthene are exonyms of Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term Rutheni was used in medieval sources to describe all Eastern Slavs of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, as an exonym for people of the former Kievan Rus', thus including ancestors of the modern Belarusians, Rusyns and Ukrainians. The use of Ruthenian and related exonyms continued through the early modern period, developing several distinctive meanings, both in terms of their regional scopes and additional religious connotations.

Polish people, or Poles, are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Central Europe. The preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of Poland defines the Polish nation as comprising all the citizens of Poland, regardless of heritage or ethnicity. The majority of Poles adhere to Roman Catholicism.

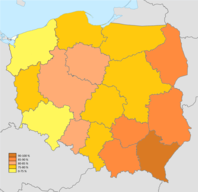

Polish members of the Catholic Church, like elsewhere in the world, are under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome. The Latin Church and its Episcopal Conference of Poland includes 41 dioceses of the Latin Church; Polish Eastern Catholics are organized under three eparchies. Combined, these comprise about 10,000 parishes and religious orders. There are 40.55 million registered Catholics in Poland. The primate of the Church is Wojciech Polak, Archbishop of Gniezno. In the early 2000s, 99% of all children born in Poland were baptized Catholic. In 2015, the church recorded that 97.7% of Poland's population was Catholic. Other statistics suggested this proportion of adherents to Catholicism could be as low as 85%. The rate of decline has been described as "devastating" the former social prestige and political influence that the Catholic Church in Poland once enjoyed. On the other hand, a 2023 survey of 36 countries with large Catholic populations using data from the World Values Survey revealed that 52% of Polish Catholics claimed to attend Mass weekly, the seventh highest of the nations surveyed and the highest among European countries. Most Poles adhere to Roman Catholicism. About 71.3% of the population identified themselves as such in the 2021 census, down from 88% in 2011.

Góra Kalwaria is a town on the Vistula River in the Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. It is situated approximately 35 kilometres southeast of Warsaw and has a population of around 12,109. The town has strong religious significance for both Catholic Christians and Hasidic Jews of the Ger dynasty.

Węgrów is a town in eastern Poland with 12,796 inhabitants (2013), capital of Węgrów County in the Masovian Voivodeship.

The city of Vilnius, now the capital of Lithuania, and its surrounding region has been under various states. The Vilnius Region has been part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the Lithuanian state's founding in the late Middle Ages to its destruction in 1795, i.e. five centuries. From then, the region was occupied by the Russian Empire until 1915, when the German Empire invaded it. After 1918 and throughout the Lithuanian Wars of Independence, Vilnius was disputed between the Republic of Lithuania and the Second Polish Republic. After the city was seized by the Republic of Central Lithuania with Żeligowski's Mutiny, the city was part of Poland throughout the Interwar period. Regardless, Lithuania claimed Vilnius as its capital. During World War II, the city changed hands many times, and the German occupation resulting in the destruction of Jews in Lithuania. From 1945 to 1990, Vilnius was the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic's capital. From the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Vilnius has been part of Lithuania.

The Polish Autocephalous Orthodox Church, commonly known as the Polish Orthodox Church, or Orthodox Church of Poland, is one of the autocephalous Eastern Orthodox churches in full communion. The church was established in 1924, to accommodate Orthodox Christians of Polish descent in the eastern part of the country, when Poland regained its independence after the First World War.

Brzeziny is a town in Poland, in Łódź Voivodeship, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) east of Łódź. It is the capital of Brzeziny County and has a population of 12,326 as of December 2021. It is situated on the Mrożyca River within the historic Łęczyca Land.

The Native Polish Church, or Native Church of Poland is a West Slavic pagan religious association that adverts to ethnic, pre-Christian beliefs of the Slavic peoples. The religion has its seat in Warsaw, with local temples throughout the country.

Margonin is a town in Chodzież County, Greater Poland Voivodeship, Poland, with 3,022 inhabitants (2016).

Obrzycko is a town in Szamotuły County, Greater Poland Voivodeship, Poland, with 2,262 inhabitants (2010).

The Polish Reformed Church, officially called the Evangelical Reformed Church in the Republic of Poland is a historic Calvinistic Protestant church in Poland established in the 16th century, still in existence today.

Armenians in Poland have an important and historical presence going back to the 14th century. According to the Polish census of 2021 there are 6,772 ethnic Armenians in Poland.

The Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in the Republic of Poland is a Lutheran denomination and the largest Protestant body in Poland with about 61,000 members and 133 parishes.

The Polish census of 1931 or Second General Census in Poland was the second census taken in sovereign Poland during the interwar period, performed on December 9, 1931 by the Main Bureau of Statistics. It established that Poland's population amounted to almost 32 million people.

The Pentecostal Church in Poland is a Pentecostal Christian denomination in Poland. It is the largest Pentecostal denomination in Poland and a part of the World Assemblies of God Fellowship, and the second largest Protestant denomination in Poland. The Pentecostal Church in Poland is a member of Pentecostal European Fellowship and Biblical Society in Poland. Headquartered in the city of Warsaw.

Protestantism in Poland is the third largest faith in Poland, after the Roman Catholic Church (32,440,722) and the Polish Orthodox Church (503,996). As of 2018 there were 103 registered Protestant denominations in Poland, and in 2023 there were 130,000 Protestants in the country.

The demographics of Poland constitute all demographic features of the population of Poland including population density, ethnicity, education level, the health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations, and other aspects of the population.

Atheism and irreligion is uncommon in Poland with Catholic Christianity as the largest faith. However, it is on the rise, which has caused tensions in the country. According to a 2020 CBOS survey, non-believers make up 3% of Poland's population.

The Lutheran Diocese of Warsaw is one of the six dioceses of the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Poland, covering most of central and eastern Poland. The Lutheran population in the area in 2016 was 3968, which amounts to about 7% of the total number of adherents of the church in Poland. There were 18 ordained ministers in the diocese in 2016.