SAVAK, an acronym of Sāzmān-e Ettelā'āt va Amniyat-e Keshvar, was the secret police of the Imperial State of Iran. It was established in Tehran in 1957 and continued to operate until the Islamic Revolution in 1979, when it was dissolved by Iranian prime minister Shapour Bakhtiar, who was assassinated by the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1991.

The Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas, also known as the Dehghani faction after its leader Ashraf Dehghani, is an Iranian communist organization that split from the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (OIFPG) in 1979, dropping the word "organization" from its name.

Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (Minority) (Persian: سازمان چريکهای فدايی خلق ايران (اقليت), romanized: Sāzmān-e čerikhā-ye Fadāʾi-e ḵalq-e Irān (aqallīyat)) was an Iranian Marxist–Leninist organisation. An offshoot of the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas, it split from the majority faction, adhering to its original militant policy of opposing the Tudeh Party and challenging the Islamic Republic.

The Organization of Iranian People's Fadaian (Majority) (Persian: سازمان فدائیان خلق ایران (اکثریت), romanized: Sāzmān-e fedaiyān-e khalq-e Irān (aksariat); lit. 'Organization of self-sacrificers of the people of Iran') is an Iranian left-wing opposition political party in exile. The OIPFM advocates for an Iranian secular republic and the overthrow the current Islamic Republic of Iran government.

The Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas, simply known as Fadaiyan-e-Khalq was an underground Marxist–Leninist guerrilla organization in Iran.

Hassan Zia-Zarifi was an Iranian intellectual and one of the ideological founders of the communist guerrilla movement in Iran.

The Organization of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, or simply Peykar, also known by the earlier name Marxist Mojahedin, was a splinter group from the People's Mojahedin of Iran (PMOI/MEK).

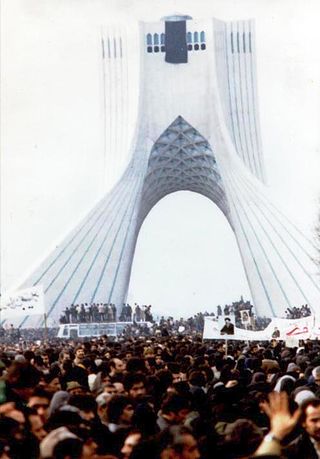

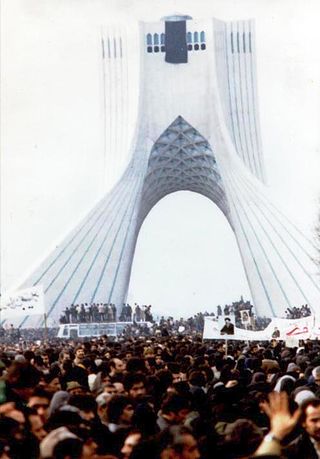

Many organizations, parties and guerrilla groups were involved in the Iranian Revolution. Some were part of Ayatollah Khomeini's network and supported the theocratic Islamic Republic movement, while others did not and were suppressed when Khomeini took power. Some groups were created after the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty and still survive; others helped overthrow the Shah but no longer exist.

Hamid Ashraf was one of the original member and later the leader of the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (OIPFG) that waged a guerrilla warfare against the former Pahlavi regime in Iran from February 8, 1971, till February 11, 1979, the Shah's fall. Hamid Ashraf played a key role in consolidating the OIPFG as a militant armed organisation against the Shah's regime.

Homa Nategh was an Iranian historian, Professor of History at University of Tehran. A specialist in the contemporary history of Iran, she resided in Paris, France, until her death. She was active during Iran's 1979 revolution. After the revolution she was purged from the University of Tehran and moved to Paris, where she was appointed as professor of the Iranian Studies at the Sorbonne. In Sorbonne she published several articles on Iranian history in Qajar period.

Socialism in Iran or Iranian socialism is a political ideology that traces its beginnings to the 20th century and encompasses various political parties in the country. Iran experienced a short Third World Socialism period at the zenith of the Tudeh Party after the abdication of Reza Shah and his replacement by his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. After failing to reach power, this form of third world socialism was replaced by Mosaddegh's populist, non-aligned Iranian nationalism of the National Front party as the main anti-monarchy force in Iran, reaching power (1949–1953), and it remained with that strength even in opposition until the rise of Islamism and the Iranian Revolution. The Tudehs have moved towards basic socialist communism since then.

Taher Ahmadzadeh Heravi was an Iranian nationalist-religious political activist who held office as the first governor of Khorasan Province after the Iranian Revolution.

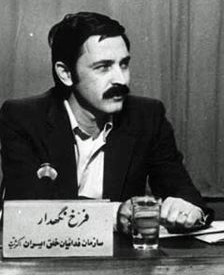

Farrokh Negahdar is an Iranian leftist political activist.

Mostafa Madani is an Iranian communist politician and one of the senior members of the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas.

Roghieh "Faran" Daneshgari is an Iranian communist who was a member of the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas.

Heshmat Raisi was an Iranian communist who was a member of the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas.

Farajollah Mizani, also known by pseudonym and pen name Javanshir, was an Iranian communist and a senior Tudeh Party member.

Marzieh Ahmadi or Uskulu Marziyya was an Iranian poet, teacher, revolutionary, and a prominent female member of the resistance movement against the regime of the Shah. She was a member of the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas. She died in a shootout with SAVAK in 1974.

The Turkmen People's Cultural and Political Society, also known as the Turkmensahra Councils Central Headquarters, was a Marxist-Leninist and ethnic insurgent group based in Gonbad-e Kavus, Iran.

Anarchism in Iran has its roots in a number of dissident religious philosophies, as well as in the development of anti-authoritarian poetry throughout the rule of various imperial dynasties over the country. In the modern era, anarchism came to Iran during the late 19th century and rose to prominence in the wake of the Constitutional Revolution, with anarchists becoming leading members of the Jungle Movement that established the Persian Socialist Soviet Republic in Gilan.