The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that sets the basis for the relationship between the Dominions and the Crown.

The High Court of Australia is the apex court of the Australian legal system. It exercises original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified in the Constitution of Australia and supplementary legislation.

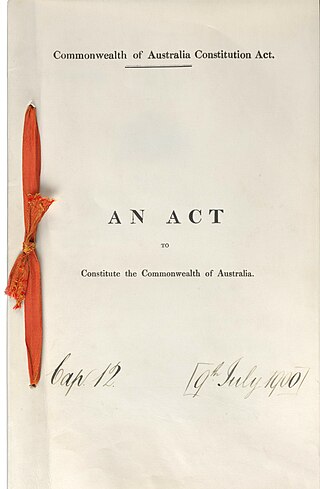

Australian constitutional law is the area of the law of Australia relating to the interpretation and application of the Constitution of Australia. Legal cases regarding Australian constitutional law are often handled by the High Court of Australia, the highest court in the Australian judicial system. Several major doctrines of Australian constitutional law have developed.

Amalgamated Society of Engineers v Adelaide Steamship Co Ltd, commonly known as the Engineers case, was a landmark decision by the High Court of Australia on 31 August 1920. The immediate issue concerned the Commonwealth's power under s 51(xxxv) of the Constitution but the court did not confine itself to that question, using the opportunity to roam broadly over constitutional interpretation.

The judiciary of Australia comprises judges who sit in federal courts and courts of the States and Territories of Australia. The High Court of Australia sits at the apex of the Australian court hierarchy as the ultimate court of appeal on matters of both federal and State law.

The legal system of Australia has multiple forms. It includes a written constitution, unwritten constitutional conventions, statutes, regulations, and the judicially determined common law system. Its legal institutions and traditions are substantially derived from that of the English legal system. Australia is a common-law jurisdiction, its court system having originated in the common law system of English law. The country's common law is the same across the states and territories.

Australian administrative law defines the extent of the powers and responsibilities held by administrative agencies of Australian governments. It is basically a common law system, with an increasing statutory overlay that has shifted its focus toward codified judicial review and to tribunals with extensive jurisdiction.

In Australian constitutional law, chapter III courts are courts of law which are a part of the Australian federal judiciary and thus are able to discharge Commonwealth judicial power. They are so named because the prescribed features of these courts are contained in chapter III of the Australian Constitution.

The monarchy of Australia is a key component of Australia's form of government, embodied by the Australian sovereign and head of state. The Australian monarchy is a constitutional one, modelled on the Westminster system of parliamentary government, while incorporating features unique to the constitution of Australia.

Commonwealth v Bank of New South Wales, was a Privy Council decision that affirmed the High Court of Australia's decision in Bank of New South Wales v Commonwealth, promoting the theory of "individual rights" to ensure freedom of interstate trade and commerce. The case dealt primarily with Section 92 of the Constitution of Australia.

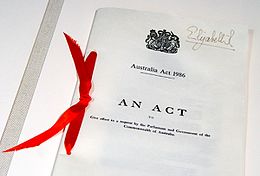

Sue v Hill was an Australian court case decided in the High Court of Australia on 23 June 1999. It concerned a dispute over the apparent return of a candidate, Heather Hill, to the Australian Senate in the 1998 federal election. The result was challenged on the basis that Hill was a dual citizen of the United Kingdom and Australia, and that section 44(i) of the Constitution of Australia prevents any person who is the citizen of a "foreign power" from being elected to the Parliament of Australia. The High Court found that, at least for the purposes of section 44(i), the United Kingdom is a foreign power to Australia.

Bank of New South Wales v The Commonwealth, also known as the Bank Nationalisation Case, is a decision of the High Court of Australia that dealt with the constitutional requirements for property to be acquired on "just terms", and for interstate trade and commerce to be free. The High Court applied an 'individual rights' theory to the freedom of interstate trade and commerce that lasted until 1988, when it was overturned in favour a 'free trade' interpretation in Cole v Whitfield.

D'Emden v Pedder was a significant Australian court case decided in the High Court of Australia on 26 April 1904. It directly concerned the question of whether salary receipts of federal government employees were subject to state stamp duty, but it touched on the broader issue within Australian constitutional law of the degree to which the two levels of Australian government were subject to each other's laws.

Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd , was a decision of the High Court of Australia on 17 April 1985 concerning section 74 of the Constitution of Australia. The Court denied an application by the Attorney-General of Queensland seeking a certificate that would permit the Privy Council to hear an appeal from the High Court's decision in Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd .

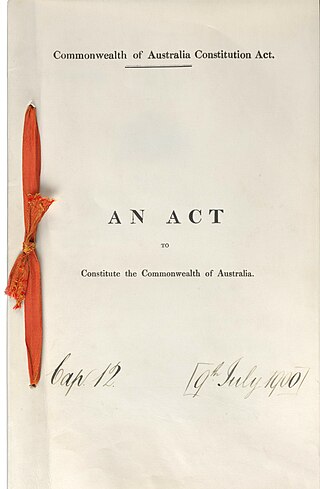

The Constitution of Australia is the fundamental law that governs the political structure of Australia. It is a written constitution, that establishes the country as a federation under a constitutional monarchy governed with a parliamentary system. Its eight chapters sets down the structure and powers of the three constituent parts of the federal level of government: the Parliament, the executive government and the judicature.

Australian corporations law has historically borrowed heavily from UK company law. Its legal structure now consists of a single, national statute, the Corporations Act 2001. The statute is administered by a single national regulatory authority, the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC).

Colonial Sugar Refining Co Ltd v Attorney-General (Cth), is the only case in which the High Court issued a certificate under section 74 of the Constitution to permit an appeal to the Privy Council on a constitutional question. The Privy Council did not answer the question asked by the High Court, and the court never issued another certificate of appeal.

Deakin v Webb was one of a series of cases concerning whether the States could tax the income of a Commonwealth officer. The High Court of Australia overruled a decision of the Supreme Court of Victoria, holding that the States could not tax the income of a Commonwealth officer. This resulted in conflict with the Privy Council that was ultimately resolved by the passage of Commonwealth law in 1907 to permit the States to tax the income of a Commonwealth officer. The constitutional foundation of the decision was overturned by the subsequent decision of the High Court in the 1920 Engineers' Case.

Baxter v Commissioners of Taxation (NSW), and Flint v Webb, were the last of a series of cases concerning whether the States could tax the income of a Commonwealth officer which had resulted in conflict between the High Court and the Privy Council. The two cases were heard together, however two separate judgments were issued with Baxter v Commissioners of Taxation (NSW) addressing the substantive issues, and Flint v Webb addressing the applications for a certificate to appeal to the Privy Council. The judgement of Griffith CJ in Flint v Webb suggested two ways in which that conflict could be resolved. Both suggestions were adopted by the Commonwealth Parliament by legislation that permitted the States to tax the income of a Commonwealth officer, and gave the High Court exclusive appellate jurisdiction on such constitutional questions. The constitutional foundation of the decision was overturned by the subsequent decision of the High Court in the 1920 Engineers' case.

The Constitution of New South Wales is composed of both unwritten and written elements that set out the structure of Government in the State of New South Wales. While the most important parts are codified in the Constitution Act 1902, major parts of the broader constitution can also be found in: