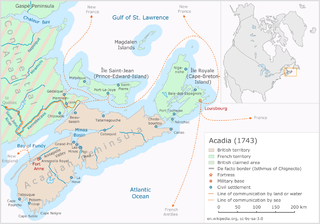

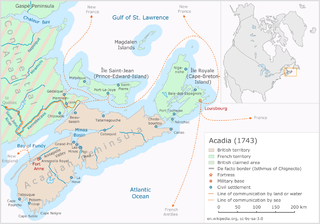

The Expulsion of the Acadians is the term used for the forced removal between 1755 and 1764 by Britain of inhabitants of the North American region historically known as Acadia. It included the modern Canadian Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, along with the U.S. state of Maine. The Expulsion occurred during the French and Indian War, the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War.

Charles Deschamps de Boishébert was a member of the Compagnies Franches de la Marine and was a significant leader of the Acadian militia's resistance to the Expulsion of the Acadians. He settled and tried to protect Acadians refugees along the rivers of New Brunswick. At Beaubears National Park on Beaubears Island, New Brunswick he settled refugee Acadians during the Expulsion of the Acadians.

The history of Prince Edward Island covers several historical periods, from the pre-Columbian era to the present day. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the island formed a part of Mi'kma'ki, the lands of the Mi'kmaq people. The island was first explored by Europeans in the 16th century. The French later laid claim over the entire Maritimes region, including Prince Edward Island in 1604. However, the French did not attempt to settle the island until 1720, with the establishment of the colony of Île Saint-Jean. After peninsular Acadia was captured by the British in 1710, an influx of Acadian migrants moved to areas still under French control, including Île Saint-Jean.

The Battle of Grand Pré, also known as the Battle of Minas and the Grand Pré Massacre, was a battle in King George's War that took place between New England forces and Canadian, Mi'kmaq and Acadian forces at present-day Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia in the winter of 1747 during the War of the Austrian Succession. The New England forces were contained to Annapolis Royal and wanted to secure the head of the Bay of Fundy. Led by Nicolas Antoine II Coulon de Villiers and Louis de la Corne, Chevalier de la Corne under orders from Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Roch de Ramezay, the French forces surprised and defeated a force of British troops, Massachusetts militia and rangers that were quartered in the village.

The Hillsborough River, also known as the East River, is a Canadian river in northeastern Queens County, Prince Edward Island.

Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre was a Catholic priest and missionary for the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Le Loutre became the leader of the French forces and the Acadian and Mi'kmaq militias during King George's War and Father Le Loutre's War in the eighteenth-century struggle for power between the French, Acadians, and Miꞌkmaq against the British over Acadia.

Abbé Pierre Antoine Simon Maillard was a French-born priest. He is noted for his contributions to the creation of a writing system for the Mi'kmaq people of Île Royale, New France. He is also credited with helping negotiate a peace treaty between the British and the Mi'kmaq that resulted in the Burying the Hatchet ceremony. He was the first Catholic priest in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and is buried in the St. Peter's Cemetery, in Downtown Halifax.

Skmaqn–Port-la-Joye–Fort Amherst is a National Historic Site located in Rocky Point, Prince Edward Island.

The Raid on Canso was an attack by French forces from Louisbourg on the British outpost Fort William Augustus at Canso, Nova Scotia shortly after war declarations opened King George's War. The French raid was intended to boost morale, secure Louisbourg's supply lines with the surrounding Acadian settlements, and deprive Britain of a base from which to attack Louisbourg. There were 50 English families in the settlement. While the settlement was utterly destroyed, the objective failed, since the British launched an attack on Louisbourg in 1745, using Canso as a staging area.

John Rous was a Royal Navy officer and privateer. He served during King George's War and the French and Indian War. Rous was also the senior naval officer on the Nova Scotia station during Father Le Loutre's War. Rous' daughter Mary married Richard Bulkeley and is buried in the Old Burying Ground in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The siege of Annapolis Royal in 1744 involved two of four attempts by the French, along with their Acadian and native allies, to regain the capital of Nova Scotia/Acadia, Annapolis Royal, during King George's War. The siege is noted for Governor of Nova Scotia Paul Mascarene successfully defending the last British outpost in the colony and for the first arrival of New England Ranger John Gorham to Nova Scotia. The French and Mi'kmaq land forces were thwarted on both attempts on the capital because of the failure of French naval support to arrive.

The Duc d'Anville expedition was sent from France to recapture Louisbourg and take peninsular Acadia. The expedition was the largest military force ever to set sail for the New World prior to the American Revolutionary War. This effort was the fourth and final French attempt to regain the Nova Scotian capital, Annapolis Royal, during King George's War. The Expedition was also supported on land by a force from Quebec under the command of Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Roch de Ramezay. Along with recapturing Acadia from the British, d'Anville was ordered to "consign Boston to flames, ravage New England and waste the British West Indies." News of the expedition spread fear throughout New York and New England.

The St. John River campaign occurred during the French and Indian War when Colonel Robert Monckton led a force of 1150 British soldiers to destroy the Acadian settlements along the banks of the Saint John River until they reached the largest village of Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas in February 1759. Monckton was accompanied by Captain George Scott as well as New England Rangers led by Joseph Goreham, Captain Benoni Danks, as well as William Stark and Moses Hazen, both of Rogers' Rangers.

The Petitcodiac River campaign was a series of British military operations from June to November 1758, during the French and Indian War, to deport the Acadians that either lived along the Petitcodiac River or had taken refuge there from earlier deportation operations, such as the Ile Saint-Jean campaign. Under the command of George Scott, William Stark's company of Rogers Rangers, Benoni Danks and Gorham's Rangers carried out the operation.

The Gulf of St. Lawrence campaign occurred during the French and Indian War when British forces raided villages along present-day New Brunswick and the Gaspé Peninsula coast of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Sir Charles Hardy and Brigadier-General James Wolfe were in command of the naval and military forces respectively. After the siege of Louisbourg, Wolfe and Hardy led a force of 1,500 troops in nine vessels to the Gaspé Bay arriving there on September 5. From there they dispatched troops to Miramichi Bay, Grande-Rivière, Quebec and Pabos, and Mont-Louis, Quebec. Over the following weeks, Sir Charles Hardy took 4 sloops or schooners, destroyed about 200 fishing vessels and took about two hundred prisoners.

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the British and New England colonists were led by British officer Charles Lawrence and New England Ranger John Gorham. On the other side, Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre led the Mi'kmaq and the Acadia militia in guerrilla warfare against settlers and British forces. At the outbreak of the war there were an estimated 2500 Mi'kmaq and 12,000 Acadians in the region.

Joseph Dupont Duvivier was an Acadian-born military leader of the French.

The military history of the Mi'kmaq consisted primarily of Mi'kmaq warriors (smáknisk) who participated in wars against the English independently as well as in coordination with the Acadian militia and French royal forces. The Mi'kmaq militias remained an effective force for over 75 years before the Halifax Treaties were signed (1760–1761). In the nineteenth century, the Mi'kmaq "boasted" that, in their contest with the British, the Mi'kmaq "killed more men than they lost". In 1753, Charles Morris stated that the Mi'kmaq have the advantage of "no settlement or place of abode, but wandering from place to place in unknown and, therefore, inaccessible woods, is so great that it has hitherto rendered all attempts to surprise them ineffectual". Leadership on both sides of the conflict employed standard colonial warfare, which included scalping non-combatants. After some engagements against the British during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century, while the Mi'kmaq people used diplomatic efforts to have the local authorities honour the treaties. After confederation, Mi'kmaq warriors eventually joined Canada's war efforts in World War I and World War II. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Chief (Sakamaw) Jean-Baptiste Cope and Chief Étienne Bâtard.

The military history of the Acadians consisted primarily of militias made up of Acadian settlers who participated in wars against the English in coordination with the Wabanaki Confederacy and French royal forces. A number of Acadians provided military intelligence, sanctuary, and logistical support to the various resistance movements against British rule in Acadia, while other Acadians remained neutral in the contest between the Franco–Wabanaki Confederacy forces and the British. The Acadian militias managed to maintain an effective resistance movement for more than 75 years and through six wars before their eventual demise. According to Acadian historian Maurice Basque, the story of Evangeline continues to influence historic accounts of the expulsion, emphasising Acadians who remained neutral and de-emphasising those who joined resistance movements. While Acadian militias were briefly active during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century. After confederation, Acadians eventually joined the Canadian War efforts in World War I and World War II. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Joseph Broussard and Joseph-Nicolas Gautier.

The Ile Saint-Jean campaign was a series of military operations in fall 1758, during the Seven Years' War, to deport the Acadians who either lived on Ile Saint-Jean or had taken refuge there from earlier deportation operations. Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew Rollo led a force of 500 British troops to take possession of Ile Saint-Jean.