The War of the Austrian Succession was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's War in North America, the War of Jenkins' Ear, the First Carnatic War and the First and Second Silesian Wars.

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, grandson of James II and VII, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1766 as Charles III. During his lifetime, he was also known as "the Young Pretender" and "the Young Chevalier"; in popular memory, he is known as Bonnie Prince Charlie.

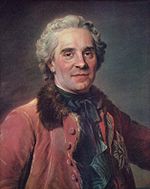

Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland was the third and youngest son of King George II of Great Britain and Ireland and his wife, Caroline of Ansbach. He was Duke of Cumberland from 1726. He is best remembered for his role in putting down the Jacobite Rising at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, which made him immensely popular throughout parts of Britain. He is often referred to by the nickname given to him by his Tory opponents: 'Butcher' Cumberland.

Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, was a British naval officer. After serving throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, he gained a reputation for his role in amphibious operations against the French coast as part of Britain's policy of naval descents during the Seven Years' War. He also took part, as a naval captain, in the decisive British naval victory at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in November 1759.

Admiral of the Blue Edward Boscawen, PC was a British admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament for the borough of Truro, Cornwall, England. He is known principally for his various naval commands during the 18th century and the engagements that he won, including the siege of Louisburg in 1758 and Battle of Lagos in 1759. He is also remembered as the officer who signed the warrant authorising the execution of Admiral John Byng in 1757, for failing to engage the enemy at the Battle of Minorca (1756). In his political role, he served as a Member of Parliament for Truro from 1742 until his death although due to almost constant naval employment he seems not to have been particularly active. He also served as one of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on the Board of Admiralty from 1751 and as a member of the Privy Council from 1758 until his death in 1761.

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC, of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the third-rate HMS Berwick, he took part in the Battle of Toulon in February 1744 during the War of the Austrian Succession. He also captured six ships of a French squadron in the Bay of Biscay in the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre in October 1747.

The Battles of Barfleur and La Hougue took place during the Nine Years' War, between 19 May O.S. and 4 June O.S. 1692. The first was fought near Barfleur on 19 May O.S., with later actions occurring between 20 May O.S. and 4 June O.S. at Cherbourg and Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue in Normandy, France.

The Battle of Quiberon Bay was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off the coast of France near St. Nazaire. The battle was the culmination of British efforts to eliminate French naval superiority, which could have given the French the ability to carry out their planned invasion of Great Britain. A British fleet of 24 ships of the line under Sir Edward Hawke tracked down and engaged a French fleet of 21 ships of the line under Marshal de Conflans. After hard fighting, the British fleet sank or ran aground six French ships, captured one and scattered the rest, giving the Royal Navy one of its greatest victories, and ending the threat of French invasion for good.

The naval Battle of Lagos took place between a British fleet commanded by Sir Edward Boscawen and a French fleet under Jean-François de La Clue-Sabran over two days in 1759 during the Seven Years' War. They fought south west of the Gulf of Cádiz on 18 August and to the east of the small Portuguese port of Lagos, after which the battle is named, on 19 August.

The Battle of Lauffeld, variously known as Lafelt, Laffeld, Lawfeld, Lawfeldt, Maastricht, or Val, took place on 2 July 1747, between Tongeren in modern Belgium, and the Dutch city of Maastricht. Part of the War of the Austrian Succession, a French army of 80,000 under Marshal Saxe defeated a Pragmatic Army of 120,000, led by the Duke of Cumberland.

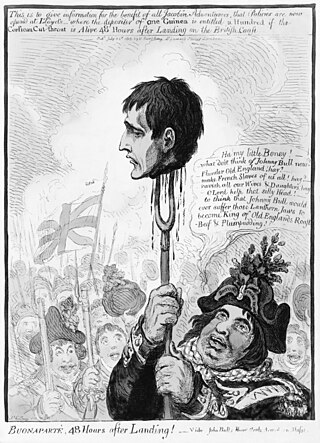

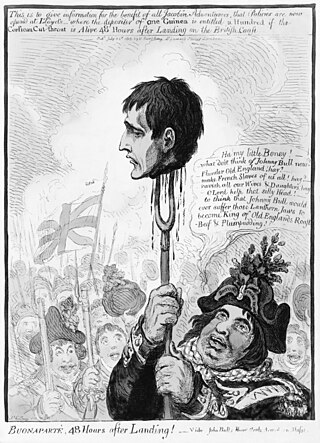

Napoleon's planned invasion of the United Kingdom at the start of the War of the Third Coalition, although never carried out, was a major influence on British naval strategy and the fortification of the coast of southeast England. French attempts to invade Ireland in order to destabilise the United Kingdom or as a stepping-stone to Great Britain had already occurred in 1796. The first French Army of England had gathered on the Channel coast in 1798, but an invasion of England was sidelined by Napoleon's concentration on campaigns in Egypt and against Austria, and shelved in 1802 by the Peace of Amiens. Building on planning for mooted invasions under France's Ancien Régime in 1744, 1759 and 1779, preparations began again in earnest soon after the outbreak of war in 1803, and were finally called off in 1805, before the Battle of Trafalgar.

François Thurot was a French privateer, merchant naval captain and smuggler who raided British shipping during the Seven Years' War.

A French invasion of Great Britain was planned to take place in 1759 during the Seven Years' War, but due to various factors was never launched. The French planned to land 100,000 French soldiers in Britain to end British involvement in the war. The invasion was one of several failed French attempts during the 18th century to invade Britain.

Great Britain was one of the major participants in the Seven Years' War, which in fact lasted nine years, between 1754 and 1763. British involvement in the conflict began in 1754 in what became known as the French and Indian War. However the warfare in the European theater involving countries other than Britain and France commenced in 1756. Britain emerged from the war as the world's leading colonial power, having gained all of New France in North America, ending France's role as a colonial power there. Following Spain's entry in the war in alliance with France in the third Family Compact, Britain captured the major Spanish ports of Havana, Cuba and Manila, in the Philippines in 1762, and agreed to return them in exchange for Florida, previously controlled by Spain. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 formally ended the conflict and Britain established itself as the world's pre-eminent naval power.

British anti-invasion preparations of 1803–05 were the military and civilian responses in the United Kingdom to Napoleon's planned invasion of the United Kingdom. They included mobilization of the population on a scale not previously attempted in Britain, with a combined military force of over 615,000 in December 1803. Much of the southern English coast was fortified, with numerous emplacements and forts built to repel the feared French landing. However, Napoleon never attempted his planned invasion and so the preparations were never put to the test.

The Planned French Invasion of Britain, 1708, also known as the 'Entreprise d’Écosse', took place during the War of the Spanish Succession. The French planned to land 5,000–6,000 soldiers in northeast Scotland to support a rising by local Jacobites that would restore James Francis Edward Stuart to the throne of Great Britain.

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45, was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of the British Army was fighting in mainland Europe, and proved to be the last in a series of revolts that began in 1689, with major outbreaks in 1708, 1715 and 1719.

The term Invasion of England may refer to the following planned or actual invasions of what is now modern England, successful or otherwise.

The Jacobite Rising of 1719 was a failed attempt to restore the exiled James Francis Edward Stuart to the throne of Great Britain. Part of a series of Jacobite risings between 1689 to 1745, it was the only one to be supported by Spain, then at war with Britain during the War of the Quadruple Alliance.

HMS Roebuck was a 44-gun, fifth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy. She took part in the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War, serving in The Channel, the Mediterranean and the West Indies. Roebuck participated in the attack on Martinique in January 1759 and the capture of Guadeloupe in April.