The Battle of Kapyong, also known as the Battle of Jiaping, was fought during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) forces—primarily Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand—and the 118th and 60th Divisions of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA). The fighting occurred during the Chinese Spring Offensive and saw the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade establish blocking positions in the Kapyong Valley, on a key route south to the capital, Seoul. The two forward battalions—the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment and 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, both battalions consisting of about 700 men each—were supported by guns from the 16th Field Regiment of the Royal Regiment of New Zealand Artillery along with two companies of US mortars and fifteen Sherman tanks. These forces occupied positions astride the valley with hastily developed defences. As thousands of soldiers from the Republic of Korea Army (ROK) began to withdraw through the valley, the PVA infiltrated the brigade position under the cover of darkness, and assaulted the 3 RAR on Hill 504 during the evening and into the following day. The U.S. mortar companies fled the battlefield, expecting an imminent PVA breakthrough at the Kapyong Valley.

The Battle of Pork Chop Hill, known as Battle of Seokhyeon-dong Northern Hill in China, comprises a pair of related Korean War infantry battles during April and July 1953. These were fought while the United Nations Command (UN) and the Chinese and North Koreans negotiated the Korean Armistice Agreement. In the US, they were controversial because of the many soldiers killed for terrain of no strategic or tactical value, although according to US sources the Chinese lost many times the number of US soldiers killed and wounded. The first battle was described in the eponymous history Pork Chop Hill: The American Fighting Man in Action, Korea, Spring 1953, by S.L.A. Marshall, from which the film Pork Chop Hill was drawn. The UN won the first battle but the Chinese won the second battle.

The Battle of Hill Eerie refers to several Korean War engagements between the United Nations Command (UN) forces and the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) in 1952 at Hill Eerie, a military outpost about 10 miles (16 km) west of Ch'orwon. It was taken several times by both sides; each sabotaging the others' position.

Major General Juan César Cordero Dávila, was the commanding officer of the 65th Infantry Regiment during the Korean War, rising to become one of the highest ranking ethnic officers in the United States Army.

Operation Commando was an offensive undertaken by United Nations Command (UN) forces during the Korean War between 3–12 October 1951. The US I Corps seized the Jamestown Line, destroying elements of the People's Volunteer Army (PVA) 42nd, 47th, 64th and 65th Armies. This prevented the PVA from interdicting the UN supply lines near Seoul.

The Battle of Pakchon, also known as the Battle of Bochuan, took place ten days after the start of the Chinese First Phase Offensive, following the entry of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) into the Korean War. The offensive reversed the United Nations Command (UN) advance towards the Yalu River which had occurred after their intervention in the wake of the North Korean invasion of South Korea at the start of the war. The battle was fought between British and Australian forces from the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade with American armour and artillery in support, and the PVA 117th Division of the 39th Army, around the village of Pakchon on the Taeryong River. After capturing Chongju on 30 October the British and Australians had been ordered to pull back to Pakchon in an attempt to consolidate the western flank of the US Eighth Army. Meanwhile, immediately following their success at Unsan against the Americans, the PVA 117th Division had attacked southward, intending to cut off the UN forces as they withdrew in the face of the unexpected PVA assault. To halt the PVA advance, the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade was ordered to defend the lower crossings of the Taeryong and Chongchon rivers as part of a rearguard, in conjunction with the US 24th Infantry Division further upstream on the right.

Outpost Harry was a remote Korean War outpost located on a tiny hilltop in what was commonly referred to as the "Iron Triangle" on the Korean Peninsula. This was an area approximately 60 miles (100 km) northeast of Seoul and was the most direct route to the South Korean capital.

The Battle of Old Baldy was a series of five engagements for Hill 266 in west-central Korea. They occurred over a period of 10 months in 1952–1953, though there was also vicious fighting both before and after these engagements.

The First Battle of Maryang-san, also known as the Defensive Battle of Maliangshan, was fought during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) forces—primarily Australian, British and Canadian—and the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA). The fighting occurred during a limited UN offensive by US I Corps, codenamed Operation Commando. This offensive ultimately pushed the PVA back from the Imjin River to the Jamestown Line and destroyed elements of four PVA armies following heavy fighting. The much smaller battle at Maryang San took place over a five-day period, and saw the 1st Commonwealth Division dislodge a numerically superior PVA force from the tactically important Kowang san, Hill 187, and Maryang san features.

The Battle of the Samichon River was fought during the final days of the Korean War between United Nations (UN) forces—primarily Australian and American—and the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA). The fighting took place on a key position on the Jamestown Line known as "the Hook", and resulted in the defending UN troops, including the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment from the 28th British Commonwealth Brigade and the US 7th Marine Regiment, repulsing numerous assaults by the PVA 137th Division during two concerted night attacks, inflicting numerous casualties on the PVA with heavy artillery and small-arms fire. The action was part of a larger, division-sized PVA attack against the US 1st Marine Division, with diversionary assaults mounted against the Australians. With the peace talks in Panmunjom reaching a conclusion, the Chinese had been eager to gain a last-minute victory over the UN forces, and the battle was the last of the war before the official signing of the Korean armistice.

The Battle of Kumsong, also known as the Jincheng Campaign, was one of the last battles of the Korean War. During the ceasefire negotiations seeking to end the Korean War, the United Nations Command (UNC) and Chinese and North Korean forces were unable to agree on the issue of prisoner repatriation. South Korean President Syngman Rhee, who refused to sign the armistice, released 27,000 North Korean prisoners who refused repatriation. This action caused an outrage among the Chinese and North Korean commands and threatened to derail the ongoing negotiations. As a result, the Chinese decided to launch an offensive aimed at the Kumsong salient. This would be the last large-scale Chinese offensive of the war, scoring a victory over the UNC forces.

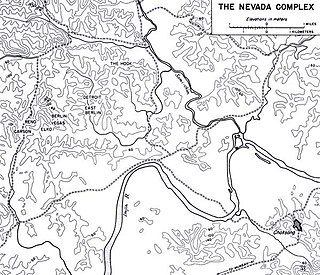

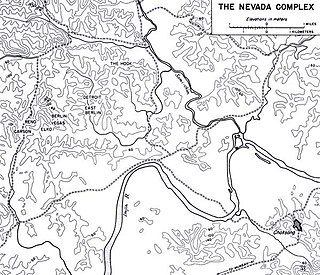

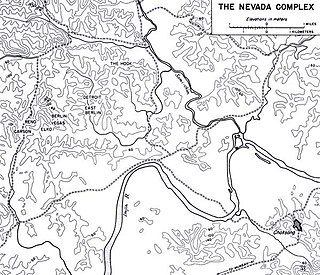

The battle for Outpost Vegas was a battle during the Korean War between the armed forces of the United Nations Command (UN) and China from 26 to 30 March 1953, four months before the end of the Korean War. Vegas was one of three outposts called the Nevada Cities north of the Main Line of Resistance (MLR), the United Nations defensive line which stretched roughly around the latitude 38th Parallel. Vegas, and the outposts it supported, Reno and Carson, were manned by elements of the 1st Marine Division. On 26 March 1953 the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) launched an attack on the Nevada Cities, including Vegas, in an attempt to better the position of China and North Korea in the Panmunjon peace talks which were occurring at the time, and to gain more territory for North Korea when its borders would be solidified. The battle raged for five days until PVA forces halted their advance after capturing one outpost north of the MLR on 30 March, but were repelled from Vegas. The battle for Outpost Vegas and the surrounding outposts are considered the bloodiest fighting to date in western Korea during the Korean War. It is estimated that there were over 1,000 American casualties and twice that number of Chinese during the Battle for Outpost Vegas. The battle is also known for the involvement of Sergeant Reckless, a horse in a USMC recoilless rifle platoon who transported ammunition and the wounded during the U.S. defense of outpost Vegas.

The Battle of Hoengsong, also known as Hoengsong Counteroffensive was a battle during the Korean War that took place between February 11–15, 1951. It was part of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) Fourth Phase Offensive and was fought between the PVA and United Nations forces. After being pushed back northward by the UN's Operation Thunderbolt counteroffensive, the PVA was victorious in this battle, inflicting heavy casualties on the UN forces in the two days of fighting and temporarily regaining the initiative.

The Battle of the Noris was a battle fought between 11 and 14 December 1952 during the Korean War between South Korean and Chinese forces on two adjacent hills known as Big Nori and Little Nori.

The Battle of the Nevada Complex was a battle fought between 25 and 29 May 1953 during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) and Chinese forces over several front line outposts. After suffering heavy losses the UN abandoned the positions.

The Battle of Bunker Hill was a battle fought between 9 August and 30 September 1952 during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) and Chinese forces over several frontline outposts.

The Battle of Jackson Heights was a battle fought between 16 and 29 October 1952 during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) and Chinese forces for possession of a UN outpost position. The Chinese successfully seized the position and defended it against UN counterattacks.

The First Battle of the Hook was a battle fought between 2 and 28 October 1952 during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) and Chinese forces over several frontline outposts.

The Battle of the Berlin Outposts and Bunker City was a battle fought between 7 and 27 July 1953 during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) and Chinese forces over several frontline outposts.

The Battle of Hwacheon was a battle fought between 22 and 26 April 1951 during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) and Chinese forces during the Chinese Spring Offensive. The US 1st Marine Division successfully defended their positions and then withdrew under fire to the No-Name Line.