Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more underneath the body, as opposed to the sprawling posture of many reptiles and salamanders.

Biarmosuchus is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids that lived around 267 mya during the Middle Permian period. Biarmosuchus was discovered in the Perm region of Russia. The first specimen was found in channel sandstone that was deposited by flood waters originating from the young Ural Mountains.

Diictodon is an extinct genus of pylaecephalid dicynodont. These mammal-like synapsids lived during the Late Permian period, approximately 255 million years ago. Fossils have been found in the Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone of the Madumabisa Mudstone of the Luangwa Basin in Zambia and the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone of the Teekloof Formation, Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone of the Abrahamskraal Formation, Dicynodon Assemblage Zone of the Balfour Formation, Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone of the Middleton or Balfour Formation of South Africa and the Guodikeng Formation of China. Roughly half of all Permian vertebrate specimens found in South Africa are those of Diictodon. This small herbivorous animal was one of the most successful synapsids in the Permian period.

Eotitanosuchus is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids whose fossils were found in the town of Ochyor in Perm Krai, Russia. It lived about 267 million years ago. The only species is Eotitanosuchus olsoni.

Dinogorgon is a genus of gorgonopsid from the Late Permian of South Africa and Tanzania. The generic name Dinogorgon is derived from Greek, meaning "terrible gorgon", while its species name rubidgei is taken from the surname of renowned Karoo paleontologist, Professor Bruce Rubidge, who has contributed to much of the research conducted on therapsids of the Karoo Basin. The type species of the genus is D. rubidgei.

Anteosaurus is an extinct genus of large carnivorous dinocephalian synapsid. It lived at the end of the Guadalupian during the Capitanian stage, about 265 to 260 million years ago in what is now South Africa. It is mainly known by cranial remains and few postcranial bones. With its skull reaching 80–90 cm (31–35 in) in length and a body size estimated at more than 5 m (16 ft) in length, and 500 to 600 kg in weight, Anteosaurus was the largest known carnivorous non-mammalian synapsid and the largest terrestrial predator of the Permian period. Occupying the top of the food chain in the Middle Permian, its skull, jaws and teeth show adaptations to capture large prey like the giants titanosuchids and tapinocephalids dinocephalians and large pareiasaurs.

Burnetiidae is an extinct family of biarmosuchian therapsids that lived in the Permian period whose fossils are found in South Africa and Russia. It contains Bullacephalus, Burnetia, Mobaceras, Niuksenitia, Paraburnetia and Proburnetia.

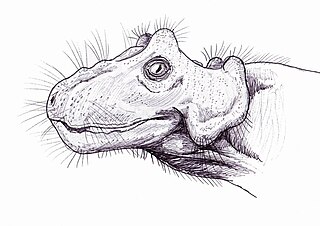

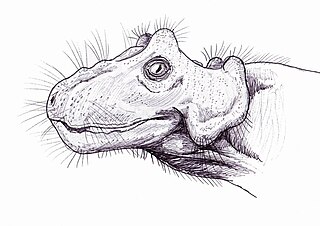

Lemurosaurus is a genus of extinct biarmosuchian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. The generic epithet Lemursaurus is a mix of Latin, lemures “ghosts, spirits”, and Greek, sauros, “lizard”. Lemurosaurus is easily identifiable by its prominent eye crests, and large eyes. The name Lemurosaurus pricei was coined by paleontologist Robert Broom in 1949, based on a single small crushed skull, measured at approximately 86 millimeters in length, found on the Dorsfontein farm in Graaff-Reinet. To date, only two skulls of the Lemurosaurus have been discovered, so body size is unknown. The second larger, more intact, skull was found in 1974 by a team from the National Museum, Bloemfontein.

Venyukovia is an extinct genus of venyukovioid therapsid, a basal anomodont from the Middle Permian of Russia. The type and sole species, V. prima, is known only by a partial lower jaw with teeth. Venyukovia has often been incorrectly spelt as 'Venjukovia' in English literature. This stems from a spelling error made by Russian palaeontologist Ivan Efremov in 1940, who mistakenly replaced the 'y' with a 'j', which subsequently permeated through therapsid literature before the mistake was caught and corrected. Venyukovia is the namesake for the Venyukovioidea, a group of small Russian basal anomodonts also including the closely related Otsheria, Suminia, Parasuminia and Ulemica, although it itself is also one of the poorest known. Like other venyukovioids, it had large projecting incisor-like teeth at the front and lacked canines, although the remaining teeth are simple compared to some other venyukovioids, but may resemble those of Otsheria.

Paraburnetia is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. It is known for its species P. sneeubergensis and belongs to the family Burnetiidae. Paraburnetia lived just before the Permian–Triassic mass extinction event.

Eosyodon is a dubious genus of extinct non-mammalian synapsids from the Permian of Texas. Its type and only species is Eosyodon hudsoni. Though it was originally interpreted as an early therapsid, it is probably a member of Sphenacodontidae, the family of synapsids that includes Dimetrodon.

Ictidorhinus is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids. Fossils have been found from the Dicynodon Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group in the Karoo Basin, South Africa and are of Late Permian age. It had a short snout and proportionally large orbits. These characteristics may be representative of a juvenile animal, possibly of Lycaenodon. However, these two genera are not known to have existed at the same time, making it unlikely for Ictidorhinus material to be from a juvenile form of Lycaenodon.

Lycaenodon is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. It is known from a single species, Lycaenodon longiceps, which was named by South African paleontologist Robert Broom in 1925. Both are small-bodied biarmosuchians. Two specimens are known, and both preserve only the front portions of the skull. These specimens come from the Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone of the Karoo Basin. Broom attributed the back portion of a third skull to Lycaenodon, but subsequent examiners considered it to belong to a gorgonopsian or dinocephalian and not a biarmosuchian. Most of the distinguishing features of Lycaenodon come from its palate. As a member of Biarmosuchia, the most basal group of therapsids, Lycaenodon shares many features with earlier and less mammal-like synapsids like Dimetrodon.

Niaftasuchus is an extinct genus of therapsids. Its type and only named species is Niaftasuchus zekkeli.

Raranimus is an extinct genus of therapsids of the Middle Permian. It was described in 2009 from a partial skull found in 1998 from the Dashankou locality of the Qingtoushan Formation, outcropping in the Qilian Mountains of Gansu, China. The genus is the most basal known member of the clade Therapsida, to which the later Mammalia belong.

Christian Alfred Sidor is an American vertebrate paleontologist. He is currently a Professor in the Department of Biology, University of Washington in Seattle, as well as Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and Associate Director for Research and Collections at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. His research focuses on Permian and Triassic tetrapod evolution, especially on therapsids.

Lende is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian from Malawi. It contains one species, Lende chiweta, first described by Jacobs and colleagues in 2005 and is a burnetiamorph – a group of biarmosuchians characterized by numerous bosses and swellings on the skull. The type specimen was discovered in the early 1990s in the Permian Lower Bone Bed (B1) of the Chiweta Beds of Malawi, which are believed to correlate with the Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone of the South African Karoo Supergroup, the Usili Formation of Tanzania, and the Upper Madumabisa Mudstone of Zambia. The holotype of the genus Lende is MAL 290, which comprises an almost complete skull and lower jaw.

Leucocephalus is a genus of biarmosuchian belonging to the family Burnetiidae dating to the Wuchiapingian. It was found in the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone of the Main Karoo Basin of South Africa. It is a monotypic taxon which contains one only species, Leucocephalus wewersi. The genus name Leucocephalus is derived from Greek. Leucos, meaning white; kephalos, meaning skull, as the Leucocephalus skull discovered was unusually pale. The species epithet wewersi comes from the farm employee who found the skull, Klaus ‘Klaasie’ Wewers.

Isengops is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids from the Late Permian of Zambia. The type species is I. luangwensis.