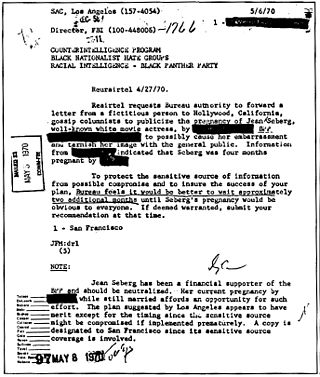

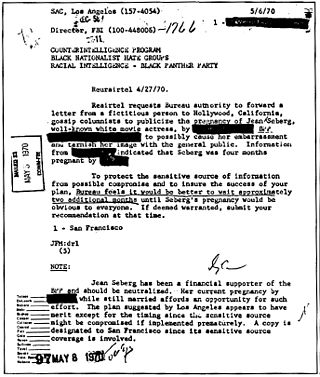

COINTELPRO was a series of covert and illegal projects actively conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic American political organizations. FBI records show COINTELPRO resources targeted groups and individuals the FBI deemed subversive, including feminist organizations, the Communist Party USA, anti–Vietnam War organizers, activists of the civil rights and Black power movements, environmentalist and animal rights organizations, the American Indian Movement (AIM), Chicano and Mexican-American groups like the Brown Berets and the United Farm Workers, independence movements, a variety of organizations that were part of the broader New Left, and white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and the far-right group National States' Rights Party.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, the FBI is also a member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and reports to both the Attorney General and the Director of National Intelligence. A leading U.S. counterterrorism, counterintelligence, and criminal investigative organization, the FBI has jurisdiction over violations of more than 200 categories of federal crimes.

Alger Hiss was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The statute of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in connection with this charge in 1950. Before the trial Hiss was involved in the establishment of the United Nations, both as a US State Department official and as a UN official. In later life, he worked as a lecturer and author.

A covert listening device, more commonly known as a bug or a wire, is usually a combination of a miniature radio transmitter with a microphone. The use of bugs, called bugging, or wiretapping is a common technique in surveillance, espionage and police investigations.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 is a United States federal law that establishes procedures for the surveillance and collection of foreign intelligence on domestic soil.

A black operation or black op is a covert or clandestine operation by a government agency, a military unit or a paramilitary organization; it can include activities by private companies or groups. Key features of a black operation are that it is secret and it is not attributable to the organization carrying it out.

Jacob Golos was a Ukrainian-born Bolshevik revolutionary who became an intelligence operative in the United States on behalf of the USSR. A founding member of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), circa 1930 Golos became involved in the covert work of Soviet intelligence agencies. He participated in procuring American passports by means of fraudulent documentation, and the recruitment and coordination of activities of a broad network of agents.

Elizabeth Terrill Bentley was an American NKVD spymaster, who was recruited from within the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). She served the Soviet Union as the primary handler of multiple highly placed moles within both the United States Federal Government and the Office of Strategic Services from 1938 to 1945. After being rendered bereft by the 1943 death of her lover, NKVD New York City station chief Jacob Golos, a heartbroken Bentley defected by contacting the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and debriefing about her own espionage activities.

William Mark Felt Sr. was an American law enforcement officer who worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1942 to 1973 and was known for his role in the Watergate scandal. Felt was an FBI special agent who eventually rose to the position of Deputy Director, the Bureau's second-highest-ranking post. Felt worked in several FBI field offices prior to his promotion to the Bureau's headquarters. In 1980, he was convicted of having violated the civil rights of people thought to be associated with members of the Weather Underground, by ordering FBI agents to break into their homes and search the premises as part of an attempt to prevent bombings. He was ordered to pay a fine, but was pardoned by President Ronald Reagan during his appeal.

Bela Gold, also Bill Gold, (1915–2012), was a Hungarian-born American businessman and professor.

The Huston Plan was a 43-page report and outline of proposed security operations put together by White House aide Tom Charles Huston in 1970. It came to light during the 1973 Watergate hearings headed by Senator Sam Ervin. According to U.S. Senator Charles Mathias, U.S. President Richard Nixon rescinded the plan on July 28, 1970, after approving it on July 23. Mathias commented that "Many constitutional lawyers believe that for five days in 1970 the fundamental guarantees of the Bill of Rights were suspended by the mandate given the secret 'Huston plan'," and that during the five days the plan was approved, "authoritarian rule had superseded the constitution." Specifically, the authorization was to suspend the protections from the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution against unreasonable searches and seizures.

Anatoly Veniaminovich Gorsky, was a Soviet spy who, under cover as First Secretary "Anatoly Borisovich Gromov" of the Soviet Embassy in Washington, was secretly rezident in the United States at the end of World War II.

Project MINARET was a domestic espionage project operated by the National Security Agency (NSA), which, after intercepting electronic communications that contained the names of predesignated US citizens, passed them to other government law enforcement and intelligence organizations. Intercepted messages were disseminated to the FBI, CIA, Secret Service, Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), and the Department of Defense. The project was a sister project to Project SHAMROCK.

The Silvermaster File of the United States' Federal Bureau of Investigation is a 162-volume compendium totalling 26,000 pages of documents relating to the FBI's investigation of GRU and NKVD moles inside the U.S. federal government both before and during the Cold War.

The Ghetto Informant Program (GIP) was an intelligence-gathering operation run by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1967 to 1973. Its official purpose was to collect information pertaining to riots and civil unrest. Through GIP, the FBI used more than 7000 people to infiltrate poor black communities in the United States.

The practice of mass surveillance in the United States dates back to wartime monitoring and censorship of international communications from, to, or which passed through the United States. After the First and Second World Wars, mass surveillance continued throughout the Cold War period, via programs such as the Black Chamber and Project SHAMROCK. The formation and growth of federal law-enforcement and intelligence agencies such as the FBI, CIA, and NSA institutionalized surveillance used to also silence political dissent, as evidenced by COINTELPRO projects which targeted various organizations and individuals. During the Civil Rights Movement era, many individuals put under surveillance orders were first labelled as integrationists, then deemed subversive, and sometimes suspected to be supportive of the communist model of the United States' rival at the time, the Soviet Union. Other targeted individuals and groups included Native American activists, African American and Chicano liberation movement activists, and anti-war protesters.

The origins of global surveillance can be traced back to the late 1940s, when the UKUSA Agreement was jointly enacted by the United Kingdom and the United States, whose close cooperation eventually culminated in the creation of the global surveillance network, code-named "ECHELON", in 1971.

Frank Edward Terpil was a CIA agent born in Brooklyn, New York, U.S. in 1939, who was asked to leave the agency for misconduct in 1971. He then "went rogue", going to work for Edwin P. Wilson's operations supplying arms, bomb making training, and surveillance equipment to numerous regimes.

The DETCOM Program, along with the COMSAB Program formed part of the "Emergency Detention Program" (1946–1950) of Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). As FBI historian Athan Theoharis described in 1978, "The FBI compiled other lists in addition to the Security Index. These include a "Comsab program", and "Detcom program", and a Communist Index