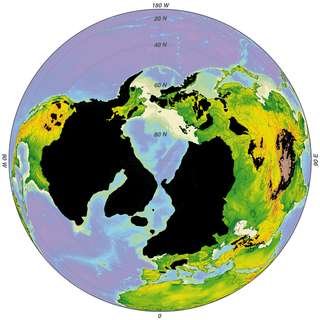

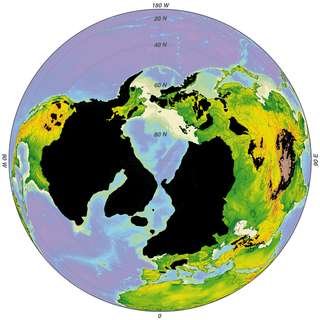

The Wisconsin Glacial Episode, also called the Wisconsin glaciation, was the most recent glacial period of the North American ice sheet complex. This advance included the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which nucleated in the northern North American Cordillera; the Innuitian ice sheet, which extended across the Canadian Arctic Archipelago; the Greenland ice sheet; and the massive Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered the high latitudes of central and eastern North America. This advance was synchronous with global glaciation during the last glacial period, including the North American alpine glacier advance, known as the Pinedale glaciation. The Wisconsin glaciation extended from approximately 75,000 to 11,000 years ago, between the Sangamonian Stage and the current interglacial, the Holocene. The maximum ice extent occurred approximately 25,000–21,000 years ago during the last glacial maximum, also known as the Late Wisconsin in North America.

The Missoula floods were cataclysmic glacial lake outburst floods that swept periodically across eastern Washington and down the Columbia River Gorge at the end of the last ice age. These floods were the result of periodic sudden ruptures of the ice dam on the Clark Fork River that created Glacial Lake Missoula. After each ice dam rupture, the waters of the lake would rush down the Clark Fork and the Columbia River, flooding much of eastern Washington and the Willamette Valley in western Oregon. After the lake drained, the ice would reform, creating Glacial Lake Missoula again.

Lake Missoula was a prehistoric proglacial lake in western Montana that existed periodically at the end of the last ice age between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago. The lake measured about 7,770 square kilometres (3,000 sq mi) and contained about 2,100 cubic kilometres (500 cu mi) of water, half the volume of Lake Michigan.

A kame, or knob, is a glacial landform, an irregularly shaped hill or mound composed of sand, gravel and till that accumulates in a depression on a retreating glacier, and is then deposited on the land surface with further melting of the glacier. Kames are often associated with kettles, and this is referred to as kame and kettle or knob and kettle topography. The word kame is a variant of comb, which has the meaning "crest" among others. The geological term was introduced by Thomas Jamieson in 1874.

Grand Coulee is an ancient river bed in the U.S. state of Washington. This National Natural Landmark stretches for about 60 miles (100 km) southwest from Grand Coulee Dam to Soap Lake, being bisected by Dry Falls into the Upper and Lower Grand Coulee.

A glacial erratic is glacially deposited rock differing from the type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics, which take their name from the Latin word errare, are carried by glacial ice, often over distances of hundreds of kilometres. Erratics can range in size from pebbles to large boulders such as Big Rock in Alberta.

The Channeled Scablands are a relatively barren and soil-free region of interconnected relict and dry flood channels, coulees and cataracts eroded into Palouse loess and the typically flat-lying basalt flows that remain after cataclysmic floods within the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Washington. The Channeled Scablands were scoured by more than 40 cataclysmic floods during the Last Glacial Maximum and innumerable older cataclysmic floods over the last two million years. These floods were periodically unleashed whenever a large glacial lake broke through its ice dam and swept across eastern Washington and down the Columbia River Plateau during the Pleistocene epoch. The last of the cataclysmic floods occurred between 18,200 and 14,000 years ago.

Dry Falls is a 3.5-mile-long (5.6 km) scalloped precipice with four major alcoves, in central Washington scablands. This cataract complex is on the opposite side of the Upper Grand Coulee from the Columbia River, and at the head of the Lower Grand Coulee, northern end of Lenore Canyon. According to the current geological model, catastrophic flooding channeled water at 65 miles per hour through the Upper Grand Coulee and over this 400-foot (120 m) rock face at the end of the last glaciation. It is estimated that the falls were five times the width of Niagara Falls, with ten times the flow of all the current rivers in the world combined.

Drumheller Channels National Natural Landmark showcases the Drumheller Channels, which are the most significant example in the Columbia Plateau of basalt butte-and-basin Channeled Scablands. This National Natural Landmark is an extensively eroded landscape, located in south central Washington state characterized by hundreds of isolated, steep-sided hills (buttes) surrounded by a braided network of numerous channels, all but one of which are currently dry. It is a classic example of the tremendous erosive powers of extremely large floods such as those that reformed the Columbia Plateau volcanic terrain during the late Pleistocene glacial Missoula Floods.

Sims Corner Eskers and Kames National Natural Landmark of Douglas County, Washington and nearby McNeil Canyon Haystack Rocks and Boulder Park natural landmarks contain excellent examples of Pleistocene glacial landforms. Sims Corner Eskers and Kames National Natural Landmark includes classic examples of ice stagnation landforms such as glacial erratics, terminal moraines, eskers, and kames. It is located on the Waterville Plateau of the Columbia Plateau in north central Washington state in the United States.

Moses Coulee is a canyon in the Waterville plateau region of Douglas County, Washington. Moses Coulee is the second-largest and westernmost canyon of the Channeled Scablands, located about 30 kilometres (19 mi) to the west of the larger Grand Coulee. This water channel is now dry, but during glacial periods, large outburst floods with discharges greater than 600,000 m3/s (21,000,000 cu ft/s) carved the channel. While it's clear that megafloods from Glacial Lake Missoula passed through and contributed to the erosion of Moses Coulee, the origins of the coulee are less clear. Some researchers propose that floods from glacial Lake Missoula formed Moses Coulee, while others suggest that subglacial floods from the Okanogan Lobe incised the canyon. The mouth of Moses Coulee discharges into the Columbia River.

The Withrow Moraine and Jameson Lake Drumlin Field is a National Park Service–designated privately owned National Natural Landmark located in Douglas County, Washington state, United States. Withrow Moraine is the only Ice Age terminal moraine on the Waterville Plateau section of the Columbia Plateau. The drumlin field includes excellent examples of glacially-formed elongated hills.

Crab Creek is a stream in the U.S. state of Washington. Named for the presence of crayfish, it is one of the few perennial streams in the Columbia Basin of central Washington, flowing from the northeastern Columbia River Plateau, roughly 5 km (3.1 mi) east of Reardan, west-southwest to empty into the Columbia River near the small town of Beverly. Its course exhibits many examples of the erosive powers of extremely large glacial Missoula Floods of the late Pleistocene, which scoured the region. In addition, Crab Creek and its region have been transformed by the large-scale irrigation of the Bureau of Reclamation's Columbia Basin Project (CBP), which has raised water table levels, significantly extending the length of Crab Creek and created new lakes and streams.

The glacial history of Minnesota is most defined since the onset of the last glacial period, which ended some 10,000 years ago. Within the last million years, most of the Midwestern United States and much of Canada were covered at one time or another with an ice sheet. This continental glacier had a profound effect on the surface features of the area over which it moved. Vast quantities of rock and soil were scraped from the glacial centers to its margins by slowly moving ice and redeposited as drift or till. Much of this drift was dumped into old preglacial river valleys, while some of it was heaped into belts of hills at the margin of the glacier. The chief result of glaciation has been the modification of the preglacial topography by the deposition of drift over the countryside. However, continental glaciers possess great power of erosion and may actually modify the preglacial land surface by scouring and abrading rather than by the deposition of the drift.

The Saddle Mountains consists of an upfolded anticline ridge of basalt in Grant County of central Washington state. The ridge, reaching to 2,700 feet, terminates in the east south of Othello, Washington near the foot of the Drumheller Channels. It continues to the west where it is broken at Sentinel Gap before ending in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains.

Withrow is an unincorporated community in Douglas County, Washington, United States.

The Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail is a network of routes connecting natural sites and facilities that provide interpretation of the geological consequences of the Glacial Lake Missoula floods of the last glacial period that occurred about 18,000 to 15,000 years ago. It includes sites in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. It was designated as the first National Geologic Trail in the United States in 2009.

Glacial Lake Columbia was the lake formed on the ice-dammed Columbia River behind the Okanogan lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet when the lobe covered 500 square miles (1,300 km2) of the Waterville Plateau west of Grand Coulee in central Washington state during the Wisconsin glaciation. Lake Columbia was a substantially larger version of the modern-day lake behind the Grand Coulee Dam. Lake Columbia's overflow – the diverted Columbia River – drained first through Foster Coulee, and as the ice dam grew, through first Moses Coulee, and finally, the Grand Coulee.

New England is a region in the North Eastern United States consisting of the states Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine. Most of New England consists geologically of volcanic island arcs that accreted onto the eastern edge of the Laurentian Craton in prehistoric times. Much of the bedrock found in New England is heavily metamorphosed due to the numerous mountain building events that occurred in the region. These events culminated in the formation of Pangaea; the coastline as it exists today was created by rifting during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. The most recent rock layers are glacial conglomerates.

Foster Coulee is a coulee in Douglas County, Washington. Like the larger Moses Coulee nearby, it was formed during the Missoula Floods at the end of the last ice age, some 14,000 years ago.