In the human brain, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is the frontal part of the cingulate cortex that resembles a "collar" surrounding the frontal part of the corpus callosum. It consists of Brodmann areas 24, 32, and 33.

In neuroanatomy, the precuneus is the portion of the superior parietal lobule on the medial surface of each brain hemisphere. It is located in front of the cuneus. The precuneus is bounded in front by the marginal branch of the cingulate sulcus, at the rear by the parieto-occipital sulcus, and underneath by the subparietal sulcus. It is involved with episodic memory, visuospatial processing, reflections upon self, and aspects of consciousness.

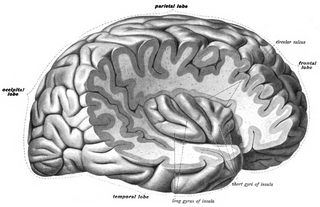

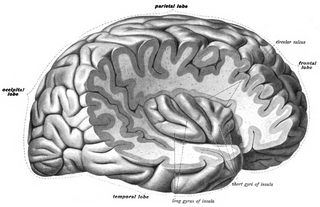

The insular cortex is a portion of the o cerebral cortex folded deep within the lateral sulcus within each hemisphere of the mammalian brain.

A gamma wave or gamma rhythm is a pattern of neural oscillation in humans with a frequency between 25 and 140 Hz, the 40 Hz point being of particular interest. Gamma rhythms are correlated with large scale brain network activity and cognitive phenomena such as working memory, attention, and perceptual grouping, and can be increased in amplitude via meditation or neurostimulation. Altered gamma activity has been observed in many mood and cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy, and schizophrenia.

Alpha waves, or the alpha rhythm, are neural oscillations in the frequency range of 8–12 Hz likely originating from the synchronous and coherent electrical activity of thalamic pacemaker cells in humans. Historically, they are also called "Berger's waves" after Hans Berger, who first described them when he invented the EEG in 1924.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) is the caudal part of the cingulate cortex, located posterior to the anterior cingulate cortex. This is the upper part of the "limbic lobe". The cingulate cortex is made up of an area around the midline of the brain. Surrounding areas include the retrosplenial cortex and the precuneus.

The sensorimotor mu rhythm, also known as mu wave, comb or wicket rhythms or arciform rhythms, are synchronized patterns of electrical activity involving large numbers of neurons, probably of the pyramidal type, in the part of the brain that controls voluntary movement. These patterns as measured by electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), or electrocorticography (ECoG), repeat at a frequency of 7.5–12.5 Hz, and are most prominent when the body is physically at rest. Unlike the alpha wave, which occurs at a similar frequency over the resting visual cortex at the back of the scalp, the mu rhythm is found over the motor cortex, in a band approximately from ear to ear. People suppress mu rhythms when they perform motor actions or, with practice, when they visualize performing motor actions. This suppression is called desynchronization of the wave because EEG wave forms are caused by large numbers of neurons firing in synchrony. The mu rhythm is even suppressed when one observes another person performing a motor action or an abstract motion with biological characteristics. Researchers such as V. S. Ramachandran and colleagues have suggested that this is a sign that the mirror neuron system is involved in mu rhythm suppression, although others disagree.

Developmental cognitive neuroscience is an interdisciplinary scientific field devoted to understanding psychological processes and their neurological bases in the developing organism. It examines how the mind changes as children grow up, interrelations between that and how the brain is changing, and environmental and biological influences on the developing mind and brain.

The psychological and physiological effects of meditation have been studied. In recent years, studies of meditation have increasingly involved the use of modern instruments, such as fMRI and EEG, which are able to observe brain physiology and neural activity in living subjects, either during the act of meditation itself or before and after meditation. Correlations can thus be established between meditative practices and brain structure or function.

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a method to record an electrogram of the spontaneous electrical activity of the brain. The biosignals detected by EEG have been shown to represent the postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex and allocortex. It is typically non-invasive, with the EEG electrodes placed along the scalp using the International 10-20 system, or variations of it. Electrocorticography, involving surgical placement of electrodes, is sometimes called "intracranial EEG". Clinical interpretation of EEG recordings is most often performed by visual inspection of the tracing or quantitative EEG analysis.

Neurocriminology is an emerging sub-discipline of biocriminology and criminology that applies brain imaging techniques and principles from neuroscience to understand, predict, and prevent crime.

Resting state fMRI is a method of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) that is used in brain mapping to evaluate regional interactions that occur in a resting or task-negative state, when an explicit task is not being performed. A number of resting-state brain networks have been identified, one of which is the default mode network. These brain networks are observed through changes in blood flow in the brain which creates what is referred to as a blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) signal that can be measured using fMRI.

Pain empathy is a specific variety of empathy that involves recognizing and understanding another person's pain.

Mindfulness has been defined in modern psychological terms as "paying attention to relevant aspects of experience in a nonjudgmental manner", and maintaining attention on present moment experience with an attitude of openness and acceptance. Meditation is a platform used to achieve mindfulness. Both practices, mindfulness and meditation, have been "directly inspired from the Buddhist tradition" and have been widely promoted by Jon Kabat-Zinn. Mindfulness meditation has been shown to have a positive impact on several psychiatric problems such as depression and therefore has formed the basis of mindfulness programs such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based pain management. The applications of mindfulness meditation are well established, however the mechanisms that underlie this practice are yet to be fully understood. Many tests and studies on soldiers with PTSD have shown tremendous positive results in decreasing stress levels and being able to cope with problems of the past, paving the way for more tests and studies to normalize and accept mindful based meditation and research, not only for soldiers with PTSD, but numerous mental inabilities or disabilities.

An identity disturbance is a deficiency or inability to maintain one or more major components of identity. These components include a sense of continuity over time; emotional commitment to representations of self, role relationships, core values and self-standards; development of a meaningful world view; and recognition of one's place in the world.

Meditation and pain is the study of the physiological mechanisms underlying meditation-specifically its neural components- that implicate it in the reduction of pain perception.

Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body, published in Great Britain as 'The Science of Meditation: How to Change Your Brain, Mind and Body', is a 2017 book by science journalist Daniel Goleman and neuroscientist Richard Davidson. The book discusses research on meditation. For the book, the authors conducted a literature review of over 6,000 scientific studies on meditation, and selected the 60 that they believed met the highest methodological standards.

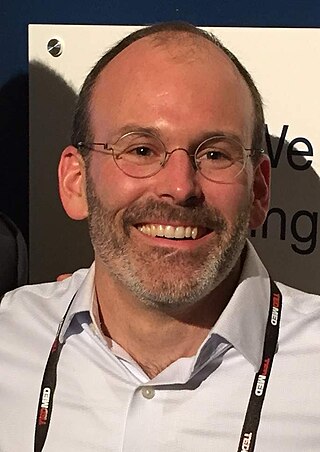

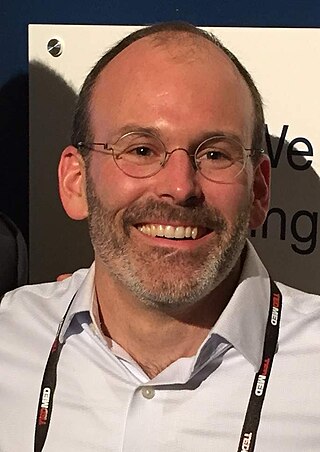

Judson Alyn Brewer, M.D., Ph.D., is an American psychiatrist, neuroscientist and New York Times best-selling author. He studies the neural mechanisms of mindfulness using standard and real-time fMRI, and has translated research findings into programs to treat addictions. Brewer founded MindSciences, Inc., an app-based digital therapeutic treatment program for anxiety, overeating, and smoking. He is director of research and innovation at Brown University's Mindfulness Center and associate professor in behavioral and social sciences in the Brown School of Public Health, and in psychiatry at Brown's Warren Alpert Medical School.

Matthew D. Sacchet is an American neuroscientist and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard University. At Massachusetts General Hospital, Sacchet directs the Meditation Research Program. His research focuses on advancing the science of meditation and includes studies of brain structure and function using multimodal neuroimaging, in addition to neurofeedback, clinical trials, and computational approaches. He is notable for his work at the intersection of neuroscience, meditation, and mental illness. His work has been cited over 4,500 times and covered by major media outlets including CBS, NBC, NPR, Time, and The Wall Street Journal. In 2017 Forbes Magazine selected Sacchet for the “30 Under 30”.