The Mildenhall Treasure is a large hoard of 34 masterpieces of Roman silver tableware from the fourth century AD, and by far the most valuable Roman objects artistically and by weight of bullion in Britain. It was found at West Row, near Mildenhall, Suffolk, in 1942. It consists of over thirty items and includes the Great Dish which weighs over 8 kg (18 lb).

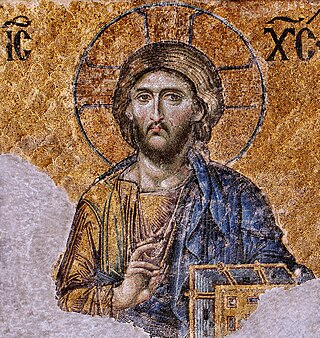

Byzantine art comprises the body of Christian Greek artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

The Melisende Psalter is an illuminated manuscript commissioned around 1135 in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, probably by Fulk, King of Jerusalem for his wife Queen Melisende. It is a notable example of Crusader art, which resulted from a merging of the artistic styles of Roman Catholic Europe, the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire and the art of the Armenian illuminated manuscript.

Niello is a black mixture, usually of sulphur, copper, silver, and lead, used as an inlay on engraved or etched metal, especially silver. It is added as a powder or paste, then fired until it melts or at least softens, and flows or is pushed into the engraved lines in the metal. It hardens and blackens when cool, and the niello on the flat surface is polished off to show the filled lines in black, contrasting with the polished metal around it. It may also be used with other metalworking techniques to cover larger areas, as seen in the sky in the diptych illustrated here. The metal where niello is to be placed is often roughened to provide a key. In many cases, especially in objects that have been buried underground, where the niello is now lost, the roughened surface indicates that it was once there.

The Harbaville Triptych is a Byzantine ivory triptych of the middle of the 10th century with a Deesis and other saints, now in the Louvre. Traces of colouring can still be seen on some figures. It is regarded as the finest, and best-preserved, of the "Romanos group" of ivories from a workshop in Constantinople, probably closely connected with the Imperial Court.

The Nea Ekklēsia was a church built by Byzantine Emperor Basil I the Macedonian in Constantinople between 876 and 880. It was the first monumental church built in the Byzantine capital after the Hagia Sophia in the 6th century, and marks the beginning of the middle period of Byzantine architecture. It continued in use until the Palaiologan period. Used as a gunpowder magazine by the Ottomans, the building was destroyed in 1490 after being struck by lightning. No traces of it survive, and information about it derives from historical accounts and depictions.

The Cross of Justin II is a processional cross dating from the sixth century that is kept in the Treasury in St. Peter's Basilica, in Vatican City. It is also one of the oldest surviving claimed reliquaries of the True Cross, if not the oldest. It is a crux gemmata or jewelled cross, silver-gilt and adorned with jewels in gold settings, given to the people of Rome by the Emperor of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, Justin II, who reigned from 565 to 578 in Constantinople, and his co-ruler and wife, the Empress Sophia.

The Monza ampullae form the largest collection of a specific type of Early Medieval pilgrimage ampullae or small flasks designed to hold holy oil from pilgrimage sites in the Holy Land related to the life of Jesus. They were made in Palestine, probably in the fifth to early seventh centuries, and have been in the Treasury of Monza Cathedral north of Milan in Italy since they were donated by Theodelinda, queen of the Lombards,. Since the great majority of surviving examples of such flasks are those in the Monza group, the term may be used to cover this type of object in general.

The Ormside Bowl is an Anglo-Saxon double-bowl in gilded silver and bronze, with glass, perhaps Northumbrian, dating from the mid-8th century which was found in 1823, possibly buried next to a Viking warrior in Great Ormside, Cumbria, though the circumstances of the find were not well recorded. If so, the bowl was probably looted from York by the warrior before being buried with him on his death. The bowl is one of the finest pieces of Anglo-Saxon silverwork found in England.

Regalia of the Russian tsars are the insignia of tsars and emperors of Russia, who ruled from the 13th to the 19th century. Over the centuries, the specific items used by Tsars changed greatly; the largest such shift occurred in the 18th century, when Peter the Great reformed the state to align it more closely with Western European monarchies.

Byzantine silk is silk woven in the Byzantine Empire (Byzantium) from about the fourth century until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Gold glass or gold sandwich glass is a luxury form of glass where a decorative design in gold leaf is fused between two layers of glass. First found in Hellenistic Greece, it is especially characteristic of the Roman glass of the Late Empire in the 3rd and 4th century AD, where the gold decorated roundels of cups and other vessels were often cut out of the piece they had originally decorated and cemented to the walls of the catacombs of Rome as grave markers for the small recesses where bodies were buried. About 500 pieces of gold glass used in this way have been recovered. Complete vessels are far rarer. Many show religious imagery from Christianity, traditional Greco-Roman religion and its various cultic developments, and in a few examples Judaism. Others show portraits of their owners, and the finest are "among the most vivid portraits to survive from Early Christian times. They stare out at us with an extraordinary stern and melancholy intensity". From the 1st century AD the technique was also used for the gold colour in mosaics.

The Caubiac Treasure is a Roman silver hoard found in the village of Thil, southern France in 1785 that is now kept in the British Museum in London.

The David Plates are a set of nine silver plates, in three sizes, stamped between 613 and 630. The plates were created in Constantinople, each depicting a scene from the life of the Hebrew king David, and associated with the reign of Emperor Heraclius (610-641). Following their discovery in Karavas in 1902, the David Plates have been considered key additions to early Byzantine secular art. It is also noted that the David Plates were found amongst the Second Cyprus Treasure. Casual laborers from the village of Karavas found the David Plates as they were quarrying the ruins for construction stones. The finders, however, failed to report what they had discovered to the Cypriot authorities. When authorities learned of their taking they confiscated three of the David Plates alongside a pair of cross-monogram plates, and other jewelry held today in the Museum of Antiquities in Nicosia. The rest of the discovery was smuggled from Cyprus and traded to a dealer located in Paris. Most of this hoard was bought by J. Pierpont Morgan and was later given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City by his heirs in 1917, where they currently remain.

The Icon of the Annunciation in St. Catherine's Monastery in Sinai, Egypt is an unusual Byzantine icon attributed to the late twelfth century. The Annunciation icon is an example of the late Komnenian-era style and was likely produced in Constantinople. The icon, tempera on wood, is one of the largest icons on display at St. Catherine's Monastery, at 61 cm high and 42.2 cm wide. Very similar Annunciation icons exist to help establish the date of the Sinai icon. One at Kurbinovo in North Macedonia, dated 1191, and the icon at Lagoudhere on Cyprus, dated 1192. The icon has distinctive elements that lead art historians, such as Evans and Wixom, to suggest the icon may have been produced at St. Catherine's Monastery itself rather than Constantinople. The Annunciation icon shares features found exclusively on other icons only at the Sinai monastery, such as the reflective circles scored in the surface of the gold and the grisaille medallion with the infant Christ on the Virgin Mary's breast.

The craft of cloisonné enameling is a metal and glass-working tradition practiced in the Byzantine Empire from the 6th to the 12th century AD. The Byzantines perfected an intricate form of vitreous enameling, allowing the illustration of small, detailed, iconographic portraits.

The Fieschi Morgan Staurotheke is a small reliquary designed to hold a relic of the true cross, it is 1 1/16 x 4 1/16 x 2 13/16 inches overall with lid. It is an example of Byzantine enameling. The box is dated to 843. Both dates hover around the second wave of Byzantine Iconoclasm from 814 to 842, allowing this piece to become a lens into the post iconoclastic art. These reliquaries doubled as an icon in style and purpose. The physical material of icons and the content within the reliquary were believed to contained a spirit or energy. It was believed that reliquaries contained great power, thus explains its preservation throughout the years. There are numerous theories of where this piece was created and its movement. It's currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum.

The Beresford Hope Cross is a 9th-century Byzantine reliquary cross with cloisonné enameling. It was intended to be worn as a pectoral crucifix, perhaps holding a fragment of the True Cross in the compartment inside. The cross is thought to have been made in southern Italy around the end of Byzantine iconoclasm, between 843 and the mid tenth century. It has been held by the Victoria and Albert Museum since 1886.

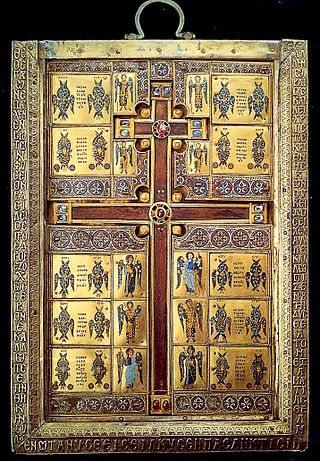

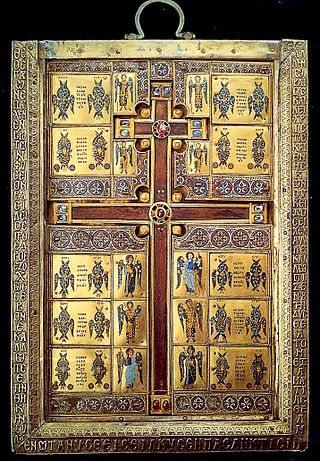

The Limburg Staurotheke is an example of a Byzantine reliquary, one of the best surviving examples of Byzantine enamel, in the cloisonné technique. It was made sometime in the mid to late 10th century in Constantinople. The box measures 48 cm (19 in) by 38 cm (15 in) and has a depth of 6 cm (2.4 in). This reliquary design was common in Byzantium beginning in the 9th century. It was probably brought to Germany as loot from the Fourth Crusade, and is now in the diocesan museum of Limburg an der Lahn in Hesse, Germany.

The silver-gilt Antioch chalice was created around AD 500-550. Currently it is on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fifth Avenue in Gallery 300. When it was discovered, the interior cup of the chalice was initially considered to be the Holy Chalice, the cup used by Christ at the Last Supper. Recently, it has been concluded that it may have been a standing oil lamp and not a chalice.