In mathematics, a continuous function is a function such that a small variation of the argument induces a small variation of the value of the function. This implies there are no abrupt changes in value, known as discontinuities. More precisely, a function is continuous if arbitrarily small changes in its value can be assured by restricting to sufficiently small changes of its argument. A discontinuous function is a function that is not continuous. Until the 19th century, mathematicians largely relied on intuitive notions of continuity and considered only continuous functions. The epsilon–delta definition of a limit was introduced to formalize the definition of continuity.

In mathematical analysis, a metric space M is called complete if every Cauchy sequence of points in M has a limit that is also in M.

In mathematics, a metric space is a set together with a notion of distance between its elements, usually called points. The distance is measured by a function called a metric or distance function. Metric spaces are the most general setting for studying many of the concepts of mathematical analysis and geometry.

In mathematics, the branch of real analysis studies the behavior of real numbers, sequences and series of real numbers, and real functions. Some particular properties of real-valued sequences and functions that real analysis studies include convergence, limits, continuity, smoothness, differentiability and integrability.

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members. The number of elements is called the length of the sequence. Unlike a set, the same elements can appear multiple times at different positions in a sequence, and unlike a set, the order does matter. Formally, a sequence can be defined as a function from natural numbers to the elements at each position. The notion of a sequence can be generalized to an indexed family, defined as a function from an arbitrary index set.

In mathematics, a real function of real numbers is said to be uniformly continuous if there is a positive real number such that function values over any function domain interval of the size are as close to each other as we want. In other words, for a uniformly continuous real function of real numbers, if we want function value differences to be less than any positive real number , then there is a positive real number such that at any and in any function interval of the size .

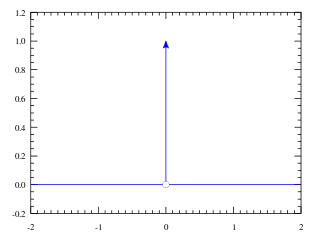

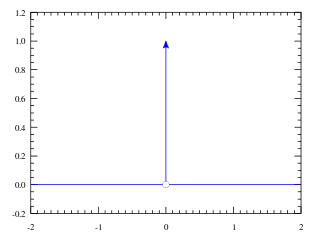

In mathematical analysis, the Dirac delta function, also known as the unit impulse, is a generalized function on the real numbers, whose value is zero everywhere except at zero, and whose integral over the entire real line is equal to one. Since there is no function having this property, to model the delta "function" rigorously involves the use of limits or, as is common in mathematics, measure theory and the theory of distributions.

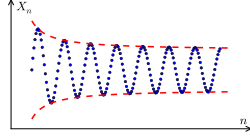

In mathematics, the limit inferior and limit superior of a sequence can be thought of as limiting bounds on the sequence. They can be thought of in a similar fashion for a function. For a set, they are the infimum and supremum of the set's limit points, respectively. In general, when there are multiple objects around which a sequence, function, or set accumulates, the inferior and superior limits extract the smallest and largest of them; the type of object and the measure of size is context-dependent, but the notion of extreme limits is invariant. Limit inferior is also called infimum limit, limit infimum, liminf, inferior limit, lower limit, or inner limit; limit superior is also known as supremum limit, limit supremum, limsup, superior limit, upper limit, or outer limit.

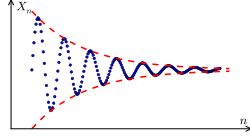

In the mathematical field of analysis, uniform convergence is a mode of convergence of functions stronger than pointwise convergence, in the sense that the convergence is uniform over the domain. A sequence of functions converges uniformly to a limiting function on a set as the function domain if, given any arbitrarily small positive number , a number can be found such that each of the functions differs from by no more than at every pointin. Described in an informal way, if converges to uniformly, then how quickly the functions approach is "uniform" throughout in the following sense: in order to guarantee that differs from by less than a chosen distance , we only need to make sure that is larger than or equal to a certain , which we can find without knowing the value of in advance. In other words, there exists a number that could depend on but is independent of , such that choosing will ensure that for all . In contrast, pointwise convergence of to merely guarantees that for any given in advance, we can find such that, for that particular, falls within of whenever .

In probability theory, there exist several different notions of convergence of sequences of random variables. The different notions of convergence capture different properties about the sequence, with some notions of convergence being stronger than others. For example, convergence in distribution tells us about the limit distribution of a sequence of random variables. This is a weaker notion than convergence in probability, which tells us about the value a random variable will take, rather than just the distribution.

In mathematics, an infinite series of numbers is said to converge absolutely if the sum of the absolute values of the summands is finite. More precisely, a real or complex series is said to converge absolutely if for some real number Similarly, an improper integral of a function, is said to converge absolutely if the integral of the absolute value of the integrand is finite—that is, if

In mathematics, the limit of a function is a fundamental concept in calculus and analysis concerning the behavior of that function near a particular input which may or may not be in the domain of the function.

In mathematics, the limit of a sequence is the value that the terms of a sequence "tend to", and is often denoted using the symbol. If such a limit exists, the sequence is called convergent. A sequence that does not converge is said to be divergent. The limit of a sequence is said to be the fundamental notion on which the whole of mathematical analysis ultimately rests.

The Arzelà–Ascoli theorem is a fundamental result of mathematical analysis giving necessary and sufficient conditions to decide whether every sequence of a given family of real-valued continuous functions defined on a closed and bounded interval has a uniformly convergent subsequence. The main condition is the equicontinuity of the family of functions. The theorem is the basis of many proofs in mathematics, including that of the Peano existence theorem in the theory of ordinary differential equations, Montel's theorem in complex analysis, and the Peter–Weyl theorem in harmonic analysis and various results concerning compactness of integral operators.

In mathematics, the Riesz–Fischer theorem in real analysis is any of a number of closely related results concerning the properties of the space L2 of square integrable functions. The theorem was proven independently in 1907 by Frigyes Riesz and Ernst Sigismund Fischer.

The Cauchy convergence test is a method used to test infinite series for convergence. It relies on bounding sums of terms in the series. This convergence criterion is named after Augustin-Louis Cauchy who published it in his textbook Cours d'Analyse 1821.

In mathematics, a sequence of functions from a set S to a metric space M is said to be uniformly Cauchy if:

In mathematics, a real number is a number that can be used to measure a continuous one-dimensional quantity such as a distance, duration or temperature. Here, continuous means that pairs of values can have arbitrarily small differences. Every real number can be almost uniquely represented by an infinite decimal expansion.

In mathematics, a limit is the value that a function approaches as the input approaches some value. Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis, and are used to define continuity, derivatives, and integrals.

In graph theory and statistics, a graphon is a symmetric measurable function , that is important in the study of dense graphs. Graphons arise both as a natural notion for the limit of a sequence of dense graphs, and as the fundamental defining objects of exchangeable random graph models. Graphons are tied to dense graphs by the following pair of observations: the random graph models defined by graphons give rise to dense graphs almost surely, and, by the regularity lemma, graphons capture the structure of arbitrary large dense graphs.