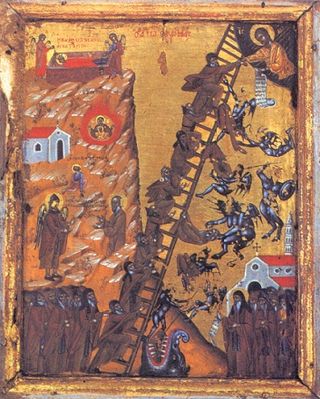

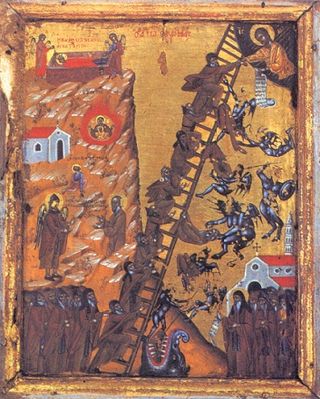

Hesychasm is a contemplative monastic tradition in the Eastern Christian traditions of the Eastern Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church in which stillness (hēsychia) is sought through uninterrupted Jesus prayer. While rooted in early Christian monasticism, it took its definitive form in the 14th century at Mount Athos.

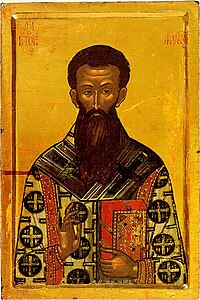

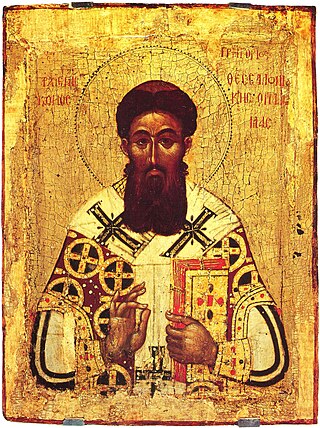

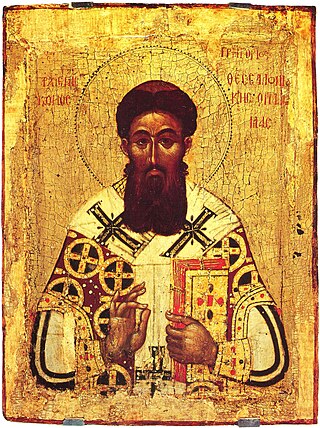

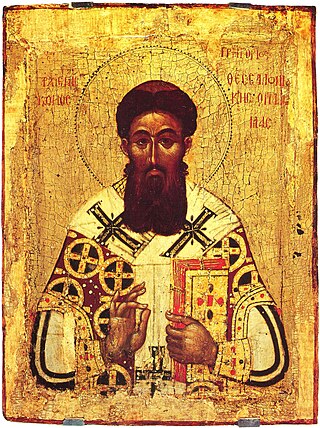

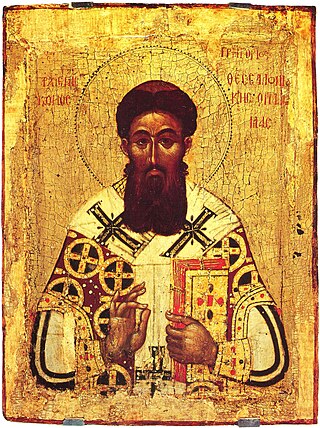

Gregory Palamas was a Byzantine Greek theologian and Eastern Orthodox cleric of the late Byzantine period. A monk of Mount Athos and later archbishop of Thessaloniki, he is famous for his defense of hesychast spirituality, the uncreated character of the light of the Transfiguration, and the distinction between God's essence and energies. His teaching unfolded over the course of three major controversies, (1) with the Italo-Greek Barlaam between 1336 and 1341, (2) with the monk Gregory Akindynos between 1341 and 1347, and (3) with the philosopher Gregoras, from 1348 to 1355. His theological contributions are sometimes referred to as Palamism, and his followers as Palamites.

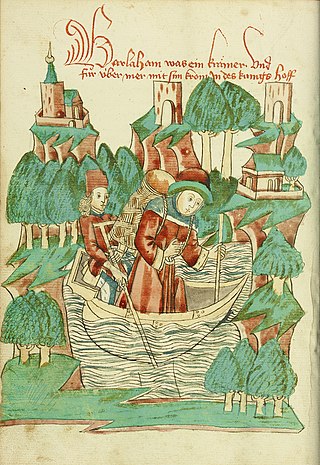

Barlaam of Seminara, c. 1290–1348, or Barlaam of Calabria was a Basilian monk, theologian and humanistic scholar born in southern Italy. He was a scholar and clergyman of the 14th century, as well as a humanist, philologist and theologian.

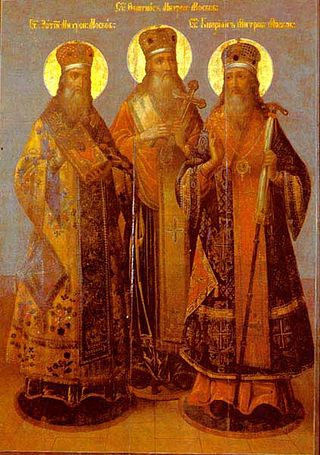

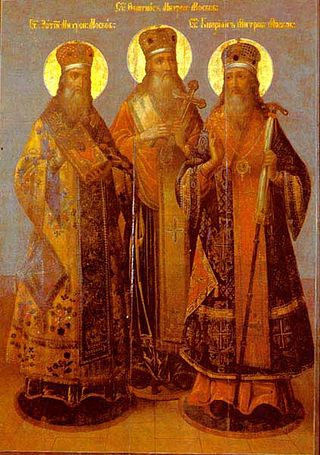

Cyprian was a prelate of Bulgarian origin, who served as the Metropolitan of Kiev, Rus' and Lithuania and the Metropolitan of Kiev and All Rus' in the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. During both periods, he was opposed by rival hierarchs and by the Grand Prince of Moscow. He was known as a bright opinion writer, editor, translator, and book copyist. He is commemorated by the Russian Orthodox Church on May 27 and September 16.

Fifth Council of Constantinople is a name given to a series of six councils held in the Byzantine capital Constantinople between 1341 and 1351, to deal with a dispute concerning the mystical doctrine of Hesychasm. These are referred to also as the Hesychast councils or the Palamite councils, since they discussed the theology of Gregory Palamas, whom Barlaam of Seminara opposed in the first of the series, and others in the succeeding five councils.

Philotheos Kokkinos was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople for two periods from November 1353 to 1354 and 1364 to 1376, and a leader of the Byzantine monastic and religious revival in the 14th century. His numerous theological, liturgical, and canonical works received wide circulation not only in Byzantium but throughout the Slavic Orthodox world.

Kallistos I was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople for two periods from June 1350 to 1353 and from 1354 to 1363. Kallistos I was an Athonite monk and supporter of Gregory Palamas. He died in Constantinople in 1363.

The history of the Eastern Orthodox Church is the formation, events, and transformation of the Eastern Orthodox Church through time. According to the Eastern Orthodox tradition, the history of the Eastern Orthodox Church is traced back to Jesus Christ and the Apostles. The Apostles appointed successors, known as bishops, and they in turn appointed other bishops in a process known as Apostolic succession. Over time, five Patriarchates were established to organize the Christian world, and four of these ancient patriarchates remain Orthodox today. Orthodox Christianity reached its present form in late antiquity, when the ecumenical councils were held, doctrinal disputes were resolved, the Fathers of the Church lived and wrote, and Orthodox worship practices settled into their permanent form.

In Eastern Orthodox Christian theology, the Tabor Light is the light revealed on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration of Jesus, identified with the light seen by Paul at his conversion.

Gregory Akindynos was a Byzantine theologian of Bulgarian origin. A native of Prilep, he moved from Pelagonia to Thessaloniki and studied under Thomas Magistros and Gregory Bryennios. He became an admirer of Nikephoros Gregoras after he was shown an astronomical treatise of that scholar by his friend Balsamon in 1332, writing him a letter in which he calls him a "sea of wisdom". From Thessaloniki, he intended to move on to Mount Athos, but for reasons unknown, he was refused.

Palamism or the Palamite theology comprises the teachings of Gregory Palamas, whose writings defended the Eastern Orthodox practice of Hesychasm against the attack of Barlaam. Followers of Palamas are sometimes referred to as Palamites.

John XIV, surnamed Kalekas, was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 1334 to 1347. He was an anti-hesychast and opponent of Gregory Palamas. He was an active participant in the Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347 as a member of the regency for John V Palaiologos, against John VI Kantakouzenos.

Isidore I was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 1347 to 1350. Isidore Buchiras was a disciple of Gregory Palamas.

The Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church have been in a state of official schism from one another since the East–West Schism of 1054. This schism was caused by historical and language differences, and the ensuing theological differences between the Western and Eastern churches.

Christianity in the Middle Ages covers the history of Christianity from the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The end of the period is variously defined. Depending on the context, events such as the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Christopher Columbus's first voyage to the Americas in 1492, or the Protestant Reformation in 1517 are sometimes used.

Theosis, or deification, is a transformative process whose aim is likeness to or union with God, as taught by the Eastern Catholic Churches and the Eastern Orthodox Church; the same concept is also found in the Latin Church of the Catholic Church, where it is termed "divinization". As a process of transformation, theosis is brought about by the effects of catharsis and theoria. According to Eastern Christian teachings, theosis is very much the purpose of human life. It is considered achievable only through synergy of human activity and God's uncreated energies.

The Triads of Gregory Palamas are a set of nine treatises entitled "Triads For The Defense of Those Who Practice Sacred Quietude" written by Gregory Palamas in response to attacks made by Barlaam. The treatises are called "Triads" because they were organized as three sets of three treatises.

The history of Eastern Orthodox Christian theology begins with the life of Jesus and the forming of the Christian Church. Major events include the Chalcedonian schism of 451 with the Oriental Orthodox miaphysites, the Iconoclast controversy of the 8th and 9th centuries, the Photian schism (863-867), the Great Schism between East and West, and the Hesychast controversy. The period after the end of the Second World War in 1945 saw a re-engagement with the Greek, and more recently Syriac Fathers that included a rediscovery of the theological works of St. Gregory Palamas, which has resulted in a renewal of Orthodox theology in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Hesychast controversy was a theological dispute in the Byzantine Empire during the 14th century between supporters and opponents of Gregory Palamas. While not a primary driver of the Byzantine Civil War, it influenced and was influenced by the political forces in play during that war. The dispute concluded with the victory of the Palamists and the inclusion of Palamite doctrine as part of the dogma of the Eastern Orthodox Church as well as the canonization of Palamas.

This is a timeline of the presence of Eastern Orthodoxy in Greece from 1204 to 1453. The history of Greece traditionally encompasses the study of the Greek people, the areas they ruled historically, as well as the territory now composing the modern state of Greece.