An antipope is a person who claims to be Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church in opposition to the legitimately elected pope. Between the 3rd and mid-15th centuries, antipopes were supported by factions within the Church itself and secular rulers.

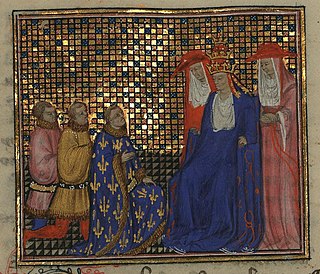

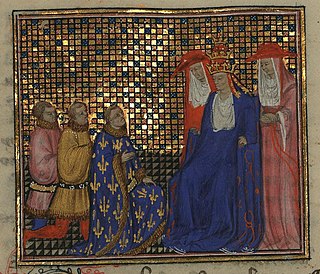

Baldassarre Cossa was Pisan antipope John XXIII (1410–1415) during the Western Schism. The Catholic Church regards him as an antipope, as he opposed Pope Gregory XII whom the Catholic Church now recognizes as the rightful successor of Saint Peter. He was also an opponent of Antipope Benedict XIII, who was recognized by the French clergy and monarchy as the legitimate Pontiff.

The Council of Constance was an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church that was held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance (Konstanz) in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the resignation of the remaining papal claimants and by electing Pope Martin V. It was the last papal election to take place outside of Italy.

Pope Gregory XI was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1370 to his death, in March 1378. He was the seventh and last Avignon pope and the most recent French pope recognized by the modern Catholic Church. In 1377, Gregory XI returned the Papal court to Rome, ending nearly 70 years of papal residency in Avignon, France. His death was swiftly followed by the Western Schism involving two Avignon-based antipopes.

Pope Gregory XII, born Angelo Corraro, Corario, or Correr, was head of the Catholic Church from 30 November 1406 to 4 July 1415. Reigning during the Western Schism, he was opposed by the Avignon claimant Benedict XIII and the Pisan claimants Alexander V and John XXIII. Gregory XII wanted to unify the Church and voluntarily resigned in 1415 to end the schism.

Pope Innocent VI, born Étienne Aubert, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 December 1352 to his death, in September 1362. He was the fifth Avignon pope and the only one with the pontifical name of "Innocent".

The Avignon Papacy was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon rather than in Rome. The situation arose from the conflict between the papacy and the French crown, culminating in the death of Pope Boniface VIII after his arrest and maltreatment by Philip IV of France. Following the subsequent death of Pope Benedict XI, Philip forced a deadlocked conclave to elect the French Clement V as pope in 1305. Clement refused to move to Rome, and in 1309 he moved his court to the papal enclave at Avignon, where it remained for the next 67 years. This absence from Rome is sometimes referred to as the "Babylonian captivity of the Papacy".

Pedro Martínez de Luna y Pérez de Gotor, known as el Papa Luna in Spanish and Pope Luna in English, was an Aragonese nobleman who, as Benedict XIII, is considered an antipope by the Catholic Church.

Guy de Malsec was a French bishop and cardinal. He was born at the family's fief at Malsec (Maillesec), in the diocese of Tulle. He had two sisters, Berauda and Agnes, who both became nuns at the Monastery of Pruliano (Pruilly) in the diocese of Carcassonne, and two nieces Heliota and Florence, who became nuns at the Monastery of S. Prassede in Avignon. He was a nephew of Pope Gregory XI, or perhaps a more distant relative. He was also a nephew of Pope Innocent VI. Guy was baptized in the church of S. Privatus, some 30 km southeast of Tulle. He played a part in the election of Benedict XIII of the Avignon Obedience in 1394, in his status as second most senior cardinal. He played an even more prominent role in Benedict's repudiation and deposition. Guy de Malsec was sometimes referred to as the 'Cardinal of Poitiers' (Pictavensis) or the 'Cardinal of Palestrina' (Penestrinus).

Rinaldo Brancaccio was an Italian cardinal from the 14th and 15th century, during the Western Schism. Other members of his family were also created cardinals: Landolfo Brancaccio (1294); Niccolò Brancaccio, pseudocardinal of Antipope Clement VII (1378); Ludovico Bonito (1408); Tommaso Brancaccio (1411); Francesco Maria Brancaccio (1633) and Stefano Brancaccio (1681). He was called the Cardinal Brancaccio.

The 1378 papal conclave which was held from April 7 to 9, 1378, was the papal conclave which was the immediate cause of the Western Schism in the Catholic Church. The conclave was one of the shortest in the history of the Catholic Church. The conclave was also the first since 1159 held in the Vatican and in Old St. Peter's Basilica.

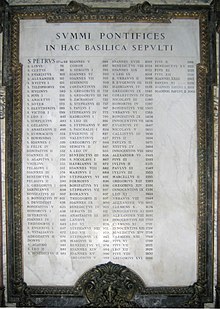

The numbering of "Popes John" does not occur in strict numerical order. Although there have been twenty-one legitimate popes named John, the numbering has reached XXIII because of two clerical errors that were introduced in the Middle Ages: first, antipope John XVI was kept in the numbering sequence instead of being removed; then, the number XX was skipped because Pope John XXI counted John XIV twice.

Louis I of Bar was a French bishop of the 15th century and the de jure Duke of Bar from 1415 to 1430, ruling from the 1420s alongside his grand-nephew René of Anjou.

Ubi periculum is a papal bull promulgated by Pope Gregory X during the Second Council of Lyon on 7 July 1274 that established the papal conclave format as the method for selecting a pope, specifically the confinement and isolation of the cardinals in conditions designed to speed them to reach a broad consensus. Its title, as is traditional for such documents, is taken from the opening words of the original Latin text, Ubi periculum maius intenditur, 'Where greater danger lies'. Its adoption was supported by the hundreds of bishops at that council over the objections of the cardinals. The regulations were formulated in response to the tactics used against the cardinals by the magistrates of Viterbo during the protracted papal election of 1268–1271, which took almost three years to elect Gregory X. In requiring that the cardinals meet in isolation, Gregory was not innovating but implementing a practice that the cardinals had either adopted on their own initiative or had forced upon them by civil authorities. After later popes suspended the rules of Ubi periculum and several were elected in traditional elections rather than conclaves, Pope Boniface VIII incorporated Ubi periculum into canon law in 1298.

Peter of Candia, also known as Peter Phillarges, named as Alexander V, was an antipope elected by the Council of Pisa during the Western Schism (1378–1417). He reigned briefly from 26 June 1409, to his death in 1410, in opposition to the Roman pope Gregory XII and the Avignon antipope Benedict XIII. In the 20th century, the Catholic Church reinterpreted the Western Schism by recognising the Roman popes, as legitimate. Gregory XII's reign was extended to 1415, and Alexander V is now regarded as an antipope.

Robert of Geneva was elected to the papacy as Clement VII by the cardinals who opposed Pope Urban VI and was the first antipope residing in Avignon, France. His election led to the Western Schism.

The Council of Pisa was a controversial council held in 1409. It attempted to end the Western Schism by deposing Benedict XIII (Avignon) and Gregory XII (Rome) for schism and manifest heresy. The College of Cardinals, composed of members of both the Avignon Obedience and the Roman Obedience, who were recognized by each other and by the Council, then elected a third papal claimant, Alexander V, who lived only a few months. He was succeeded by John XXIII.

Crusades against Christians were Christian religious wars dating from the 11th century First Crusade when papal reformers began equating the universal church with the papacy. Later in the 12th century focus changed onto heretics and schismatics rather than infidels. Holy wars were fought in northern France, against King Roger II of Sicily, various heretics, their protectors, mercenary bands and the first political crusade against Markward of Anweiler. Full crusading apparatus was deployed against Christians in the conflict with the Cathar heretics of southern France and their Christian protectors in the 13th . This was given equivalence with the Eastern crusades and supported by developments such as the creation of the Papal States. The aims were to make the crusade indulgence available to the laity, the reconfiguration of Christian society, and ecclesiastical taxation.

Giacomo Orsini, also spelled Jacopo Orsini, was a Roman prelate, the cardinal deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro from 1371 until his death shortly after the start of the Western Schism.