The Ostrogoths were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who had settled in the Balkans in the 4th century, having crossed the Lower Danube. While the Visigoths had formed under the leadership of Alaric I, the new Ostrogothic political entity which came to rule Italy was formed in the Balkans under the influence of the Amal dynasty, the family of Theodoric the Great.

Romulus Augustus, nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne by his father, the magister militum Orestes, and, at that time still a minor, was little more than a figurehead for his father. After Romulus ruled for just ten months, the barbarian general Odoacer defeated and killed Orestes and deposed Romulus. As Odoacer did not proclaim any successor, Romulus is typically regarded as the last Western Roman emperor, his deposition marking the end of the Western Roman Empire as a political entity. The deposition of Romulus Augustulus is also sometimes used by historians to mark the transition from antiquity to the medieval period.

Theodoricthe Great, also called Theodoric the Amal, was king of the Ostrogoths (475–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy between 493 and 526, regent of the Visigoths (511–526), and a patrician of the Eastern Roman Empire. As ruler of the combined Gothic realms, Theodoric controlled an empire stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Adriatic Sea. Though Theodoric himself only used the title 'king' (rex), some scholars characterize him as a Western Roman Emperor in all but name, since he ruled large parts of the former Western Roman Empire, had received the former Western imperial regalia from Constantinople in 497, and was referred to by the title augustus by some of his subjects.

The Visigoths were a Germanic people united under the rule of a king and living within the Roman Empire during late antiquity. The Visigoths first appeared in the Balkans, as a Roman-allied barbarian military group united under the command of Alaric I. Their exact origins are believed to have been diverse but they probably included many descendants of the Thervingi who had moved into the Roman Empire beginning in 376 and had played a major role in defeating the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. Relations between the Romans and Alaric's Visigoths varied, with the two groups making treaties when convenient, and warring with one another when not. Under Alaric, the Visigoths invaded Italy and sacked Rome in August 410.

Clovis was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single king and ensuring that the kingship was passed down to his heirs. He is considered to have been the founder of the Merovingian dynasty, which ruled the Frankish kingdom for the next two centuries. Clovis is important in the historiography of France as "the first king of what would become France".

The Migration Period, also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman kingdoms.

Wallia, Walha or Vallia, was king of the Visigoths from 415 to 418, earning a reputation as a great warrior and prudent ruler. He was elected to the throne after Athaulf and Sigeric were both assassinated in 415. One of Wallia's most notable achievements was negotiating a foedus with the Roman emperor Honorius in 416. This agreement allowed the Visigoths to settle in Aquitania, a region in modern-day France, in exchange for military service to Rome. This settlement marked a significant step towards the eventual establishment of a Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula. He was succeeded by Theodoric I.

Aegidius was the ruler of the short-lived Kingdom of Soissons from 461 to 464/465. Before his ascension he was an ardent supporter of the Western Roman emperor Majorian, who appointed him magister militum per Gallias in 458. After the general Ricimer assassinated Majorian and replaced him with Emperor Libius Severus, Aegidius rebelled and began governing his Gallic territory as an independent kingdom. He may have pledged his allegiance to the Eastern Roman emperor Leo I.

The Kingdom of the Franks, also known as the Frankish Kingdom, the Frankish Empire or Francia, was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Frankish Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties during the Early Middle Ages. Francia was among the last surviving Germanic kingdoms from the Migration Period era.

The term Western Roman Empire is used in modern historiography to refer to the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. Particularly during the period from 395 to 476 AD, there were separate, coequal courts dividing the governance of the empire into the Western provinces and the Eastern provinces with a distinct imperial succession in the separate courts. The terms Western Roman Empire and Eastern Roman Empire were coined in modern times to describe political entities that were de facto independent; contemporary Romans did not consider the Empire to have been split into two empires but viewed it as a single polity governed by two imperial courts for administrative expediency. The Western Empire collapsed in 476, and the Western imperial court in Ravenna disappeared by 554 AD, at the end of Justinian's Gothic War.

The Kingdom or Domain of Soissons is the historiographical name for the ethnically Roman, de facto independent remnant of the Western Roman Empire's Diocese of Gaul, which existed during Late Antiquity as an initially nominal enclave and later rump state of the Empire until its conquest by the Franks in AD 486. Its capital was at Noviodunum, today the town of Soissons in France. The rulers of the rump state, notably its final ruler Syagrius, were referred to as "kings of the Romans" by the Germanic peoples surrounding Soissons, with the polity itself being identified as the Regnum Romanorum, "Kingdom of the Romans", by the Gallo-Roman historian Gregory of Tours. Whether the title of king was used by Syagrius himself or was applied to him by the barbarians surrounding his realm is unknown.

Liuvigild, Leuvigild, Leovigild, or Leovigildo, was a Visigothic King of Hispania and Septimania from 568 to 586. Known for his Codex Revisus or Code of Leovigild, a law allowing equal rights between the Visigothic and Hispano-Roman population, his kingdom covered modern Portugal and most of modern Spain down to Toledo. Liuvigild ranks among the greatest Visigothic kings of the Arian period.

Paulus or Paul was a 7th-century Roman general in service of the Visigothic Kingdom. In 673, Paulus accompanied the Visigothic king Wamba on a campaign against the Basques, but when news reached them of a revolt led by the count Hilderic in Septimania, the northernmost and easternmost province of the kingdom, Paulus was dispatched with a considerable contingent of troops to put down the rebellion. Upon arrival in Septimania, Paulus not only completely disregarded his mission, but made himself the leader of the rebels and was anointed as king. Paulus managed to cement his authority over Septimania and the neighbouring province of Tarraconensis through the size of his army, and possibly through the two provinces being among the last properly Romanised regions of the kingdom. Titling himself as 'king of the east', Paulus ruled from Narbonne and sought to break away from Visigothic central control.

The Kingdom of Germany or German Kingdom was the mostly Germanic-speaking East Frankish kingdom, which was formed by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, especially after the kingship passed from Frankish kings to the Saxon Ottonian dynasty in 919. The king was elected, initially by the rulers of the stem duchies, who generally chose one of their own. After 962, when Otto I was crowned emperor, East Francia formed the bulk of the Holy Roman Empire, which also included the Kingdom of Italy and, after 1032, the Kingdom of Burgundy.

The Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Galicia or Suebi Kingdom of Galicia, was a Germanic post-Roman kingdom that was one of the first to separate from the Roman Empire. Based in the former Roman provinces of Gallaecia and northern Lusitania, the de facto kingdom was established by the Suebi about 409, and during the 6th century it became a formally declared kingdom identifying with Gallaecia. It maintained its independence until 585, when it was annexed by the Visigoths, and was turned into the sixth province of the Visigothic Kingdom in Hispania.

The Visigothic Kingdom, Visigothic Spain or Kingdom of the Goths occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to the Western Roman Empire, it was originally created by the settlement of the Visigoths under King Wallia in the province of Gallia Aquitania in southwest Gaul by the Roman government and then extended by conquest over all of Hispania. The Kingdom maintained independence from the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire, whose attempts to re-establish Roman authority in Hispania were only partially successful and short-lived.

The Romans were a cultural group, variously referred to as an ethnicity or a nationality, that in classical antiquity, from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD, came to rule large parts of Europe, the Near East and North Africa through conquests made during the Roman Republic and the later Roman Empire. Originally only referring to the Italic Latin citizens of Rome itself, the meaning of "Roman" underwent considerable changes throughout the long history of Roman civilisation as the borders of the Roman state expanded and contracted. At times, different groups within Roman society also had different ideas as to what it meant to be Roman. Aspects such as geography, language, and ethnicity could be seen as important by some, whereas others saw Roman citizenship and culture or behaviour as more important. At the height of the Roman Empire, Roman identity was a collective geopolitical identity, extended to nearly all subjects of the Roman emperors and encompassing vast regional and ethnic diversity.

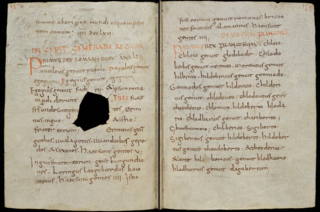

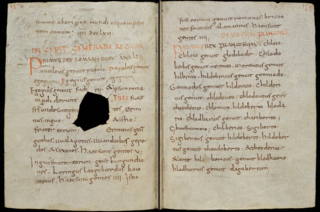

The Frankish Table of Nations is a brief early medieval genealogical text in Latin giving the supposed relationship between thirteen nations descended from three brothers. The nations are the Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Vandals, Gepids, Saxons, Burgundians, Thuringians, Lombards, Bavarians, Romans, Bretons, Franks and Alamanni.