In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, aligning with the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD and ended with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD before transitioning into the Renaissance and then the Age of Discovery. The Middle Ages is the middle period of the three traditional divisions of Western history: antiquity, medieval, and modern. The medieval period is itself subdivided into the Early, High, and Late Middle Ages. Late medieval scholars at first called these the Dark Ages in contrast to classical antiquity.

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars usually consider a castle to be the private fortified residence of a lord or noble. This is distinct from a mansion, palace and villa, whose main purpose was exclusively for pleasance and are not primarily fortresses but may be fortified. Use of the term has varied over time and, sometimes, has also been applied to structures such as hill forts and 19th- and 20th-century homes built to resemble castles. Over the Middle Ages, when genuine castles were built, they took on a great many forms with many different features, although some, such as curtain walls, arrowslits, and portcullises, were commonplace.

A royal court, often called simply a court when the royal context is clear, is an extended royal household in a monarchy, including all those who regularly attend on a monarch, or another central figure. Hence, the word court may also be applied to the coterie of a senior member of the nobility. Royal courts may have their seat in a designated place, several specific places, or be a mobile, itinerant court.

Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 6th Earl of Stafford, 7th Baron Stafford, of Stafford Castle in Staffordshire, was an English nobleman and a military commander in the Hundred Years' War and the Wars of the Roses. Through his mother he had royal descent from King Edward III, his great-grandfather, and from his father, he inherited, at an early age, the earldom of Stafford. By his marriage to a daughter of Ralph, Earl of Westmorland, Humphrey was related to the powerful Neville family and to many of the leading aristocratic houses of the time. He joined the English campaign in France with King Henry V in 1420 and following Henry V's death two years later he became a councillor for the new king, the nine-month-old Henry VI. Stafford acted as a peacemaker during the partisan, factional politics of the 1430s, when Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, vied with Cardinal Beaufort for political supremacy. Stafford also took part in the eventual arrest of Gloucester in 1447.

England in the Middle Ages concerns the history of England during the medieval period, from the end of the 5th century through to the start of the early modern period in 1485. When England emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire, the economy was in tatters and many of the towns abandoned. After several centuries of Germanic immigration, new identities and cultures began to emerge, developing into kingdoms that competed for power. A rich artistic culture flourished under the Anglo-Saxons, producing epic poems such as Beowulf and sophisticated metalwork. The Anglo-Saxons converted to Christianity in the 7th century, and a network of monasteries and convents were built across England. In the 8th and 9th centuries, England faced fierce Viking attacks, and the fighting lasted for many decades. Eventually, Wessex was established as the most powerful kingdom and promoting the growth of an English identity. Despite repeated crises of succession and a Danish seizure of power at the start of the 11th century, it can also be argued that by the 1060s England was a powerful, centralised state with a strong military and successful economy.

The Kingdom of Hungary held a noble class of individuals, most of whom owned landed property, from the 11th century until the mid-20th century. Initially, a diverse body of people were described as noblemen, but from the late 12th century only high-ranking royal officials were regarded as noble. Most aristocrats claimed ancestry from chieftains of the period preceding the establishment of the kingdom around 1000; others were descended from western European knights who settled in Hungary. The lower-ranking castle warriors also held landed property and served in the royal army. From the 1170s, most privileged laymen called themselves royal servants to emphasize their direct connection to the monarchs. The Golden Bull of 1222 established their liberties, especially tax exemption and the limitation of military obligations. From the 1220s, royal servants were associated with the nobility and the highest-ranking officials were known as barons of the realm. Only those who owned allods – lands free of obligations – were regarded as true noblemen, but other privileged groups of landowners, known as conditional nobles, also existed.

A great hall is the main room of a royal palace, castle or a large manor house or hall house in the Middle Ages, and continued to be built in the country houses of the 16th and early 17th centuries, although by then the family used the great chamber for eating and relaxing. At that time the word "great" simply meant big and had not acquired its modern connotations of excellence. In the medieval period, the room would simply have been referred to as the "hall" unless the building also had a secondary hall, but the term "great hall" has been predominant for surviving rooms of this type for several centuries, to distinguish them from the different type of hall found in post-medieval houses. Great halls were found especially in France, England and Scotland, but similar rooms were also found in some other European countries.

The late Middle Ages, late medieval period, or lower Middle Ages was the period of European history lasting from AD 1350 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period.

Scotland in the Middle Ages concerns the history of Scotland from the departure of the Romans to the adoption of major aspects of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century.

In the history of England, the High Middle Ages spanned the period from the Norman Conquest in 1066 to the death of King John, considered by some historians to be the last Angevin king of England, in 1216. A disputed succession and victory at the Battle of Hastings led to the conquest of England by William of Normandy in 1066. This linked the Kingdom of England with Norman possessions in the Kingdom of France and brought a new aristocracy to the country that dominated landholding, government and the church. They brought with them the French language and maintained their rule through a system of castles and the introduction of a feudal system of landholding. By the time of William's death in 1087, England formed the largest part of an Anglo-Norman empire, ruled by nobles with landholdings across England, Normandy and Wales. William's sons disputed succession to his lands, with William II emerging as ruler of England and much of Normandy. On his death in 1100 his younger brother claimed the throne as Henry I and defeated his brother Robert to reunite England and Normandy. Henry was a ruthless yet effective king, but after the death of his only male heir William Adelin, he persuaded his barons to recognise his daughter Matilda as heir. When Henry died in 1135 her cousin Stephen of Blois had himself proclaimed king, leading to a civil war known as The Anarchy. Eventually Stephen recognised Matilda's son Henry as his heir and when Stephen died in 1154, he succeeded as Henry II.

The history of England during the Late Middle Ages covers from the thirteenth century, the end of the Angevins, and the accession of Henry III – considered by many to mark the start of the Plantagenet dynasty – until the accession to the throne of the Tudor dynasty in 1485, which is often taken as the most convenient marker for the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the English Renaissance and early modern Britain.

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic, which reached England in June 1348. It was the first and most severe manifestation of the second pandemic, caused by Yersinia pestis bacteria. The term Black Death was not used until the late 17th century.

Women in the Middle Ages in Europe occupied a number of different social roles. Women held the positions of wife, mother, peasant, artisan, and nun, as well as some important leadership roles, such as abbess or queen regnant. The very concept of women changed in a number of ways during the Middle Ages, and several forces influenced women's roles during this period, while also expanding upon their traditional roles in society and the economy. Whether or not they were powerful or stayed back to take care of their homes, they still played an important role in society whether they were saints, nobles, peasants, or nuns. Due to context from recent years leading to the reconceptualization of women during this time period, many of their roles were overshadowed by the work of men. Although it is prevalent that women participated in church and helping at home, they did much more to influence the Middle Ages.

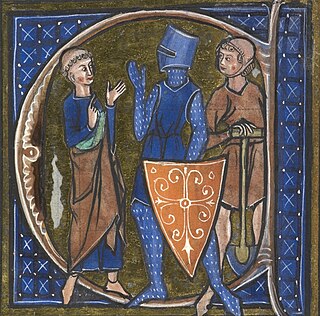

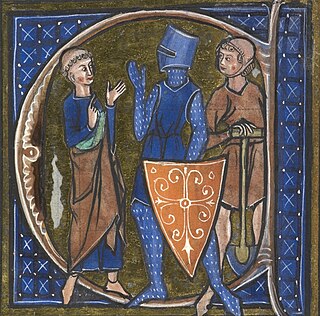

The medieval English saw their economy as comprising three groups – the clergy, who prayed; the knights, who fought; and the peasants, who worked the landtowns involved in international trade. Over the five centuries of the Middle Ages, the English economy would at first grow and then suffer an acute crisis, resulting in significant political and economic change. Despite economic dislocation in urban and extraction economies, including shifts in the holders of wealth and the location of these economies, the economic output of towns and mines developed and intensified over the period. By the end of the period, England had a weak government, by later standards, overseeing an economy dominated by rented farms controlled by gentry, and a thriving community of indigenous English merchants and corporations.

The architecture of Scotland in the Middle Ages includes all building within the modern borders of Scotland, between the departure of the Romans from Northern Britain in the early fifth century and the adoption of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century, and includes vernacular, ecclesiastical, royal, aristocratic and military constructions. The first surviving houses in Scotland go back 9500 years. There is evidence of different forms of stone and wooden houses exist and earthwork hill forts from the Iron Age. The arrival of the Romans led to the abandonment of many of these forts. After the departure of the Romans in the fifth century, there is evidence of the building of a series of smaller "nucleated" constructions sometimes utilizing major geographical features, as at Dunadd and Dumbarton. In the following centuries new forms of construction emerged throughout Scotland that would come to define the landscape.

Music in early modern Scotland includes all forms of musical production in Scotland between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. In this period the court followed the European trend for instrumental accompaniment and playing. Scottish monarchs of the sixteenth century were patrons of religious and secular music, and some were accomplished musicians. In the sixteenth century the playing of a musical instrument and singing became an expected accomplishment of noble men and women. The departure of James VI to rule in London at the Union of Crowns in 1603, meant that the Chapel Royal, Stirling Castle largely fell into disrepair and the major source of patronage was removed from the country. Important composers of the early sixteenth century included Robert Carver and David Peebles. The Lutheranism of the early Reformation was sympathetic to the incorporation of Catholic musical traditions and vernacular songs into worship, exemplified by The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567). However, the Calvinism that came to dominate Scottish Protestantism led to the closure of song schools, disbanding of choirs, removal of organs and the destruction of music books and manuscripts. An emphasis was placed on the Psalms, resulting in the production of a series of Psalters and the creation of a tradition of unaccompanied singing.

An Esquire of the Body was a personal attendant and courtier to the Kings of England during the Late Middle Ages and the early modern period. The Knight of the Body was a related position, apparently sometimes merely an "Esquire" who had been knighted, as many were. The distinction between the two roles is not entirely clear, and probably shifted over time. The positions also existed in some lesser courts, such as that of the Prince of Wales.

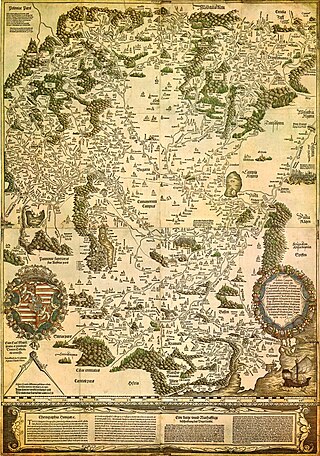

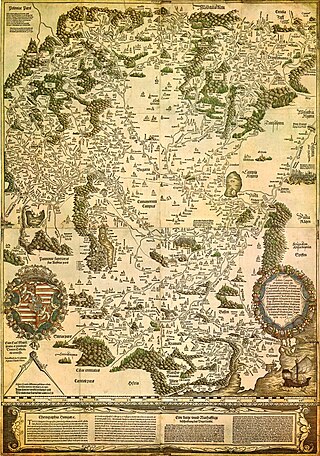

The Kingdom of Hungary came into existence in Central Europe when Stephen I, Grand Prince of the Hungarians, was crowned king in 1000 or 1001. He reinforced central authority and forced his subjects to accept Christianity. Although all written sources emphasize only the role played by German and Italian knights and clerics in the process, a significant part of the Hungarian vocabulary for agriculture, religion, and state matters was taken from Slavic languages. Civil wars and pagan uprisings, along with attempts by the Holy Roman emperors to expand their authority over Hungary, jeopardized the new monarchy. The monarchy stabilized during the reigns of Ladislaus I (1077–1095) and Coloman (1095–1116). These rulers occupied Croatia and Dalmatia with the support of a part of the local population. Both realms retained their autonomous position. The successors of Ladislaus and Coloman—especially Béla II (1131–1141), Béla III (1176–1196), Andrew II (1205–1235), and Béla IV (1235–1270)—continued this policy of expansion towards the Balkan Peninsula and the lands east of the Carpathian Mountains, transforming their kingdom into one of the major powers of medieval Europe.

The Royal Court of Scotland was the administrative, political and artistic centre of the Kingdom of Scotland. It emerged in the tenth century and continued until it ceased to function when James VI inherited the throne of England in 1603. For most of the medieval era, the king had no "capital" as such. The Pictish centre of Forteviot was the chief royal seat of the early Gaelic Kingdom of Alba that became the Kingdom of Scotland. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries Scone was a centre for royal business. Edinburgh only began to emerge as the capital in the reign of James III but his successors undertook occasional royal progress to a part of the kingdom. Little is known about the structure of the Scottish royal court in the period before the reign of David I when it began to take on a distinctly feudal character, with the major offices of the Steward, Chamberlain, Constable, Marischal and Lord Chancellor. By the early modern era the court consisted of leading nobles, office holders, ambassadors and supplicants who surrounded the king or queen. The Chancellor was now effectively the first minister of the kingdom and from the mid-sixteenth century he was the leading figure of the Privy Council.

One of the earliest documented uses of Yeoman, it refers to a servant or attendant in a late Medieval English royal or noble household. A Yeoman was usually of higher rank in the household hierarchy. This hierarchy reflected the feudal society in which they lived. Everyone who served a royal or noble household knew their duties, and knew their place. This was especially important when the household staff consisted of both nobles and commoners. There were actually two household hierarchies which existed in parallel. One was the organization based upon the function (duty) being performed. The other was based upon whether the person performing the duty was a noble or a commoner.