Climate change mitigation is action to limit the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that cause climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions are primarily caused by people burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. Phasing out fossil fuel use can happen by conserving energy and replacing fossil fuels with clean energy sources such as wind, hydro, solar, and nuclear power. Secondary mitigation strategies include changes to land use and removing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. Governments have pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but actions to date are insufficient to avoid dangerous levels of climate change.

Ecological debt refers to the accumulated debt seen by some campaigners as owed by the Global North to Global South countries, due to the net sum of historical environmental injustice, especially through resource exploitation, habitat degradation, and pollution by waste discharge. The concept was coined by Global Southerner non-governmental organizations in the 1990s and its definition has varied over the years, in several attempts of greater specification.

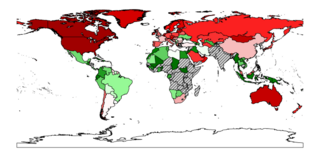

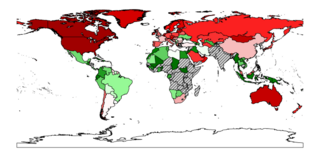

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities intensify the greenhouse effect. This contributes to climate change. Carbon dioxide, from burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, is one of the most important factors in causing climate change. The largest emitters are China followed by the United States. The United States has higher emissions per capita. The main producers fueling the emissions globally are large oil and gas companies. Emissions from human activities have increased atmospheric carbon dioxide by about 50% over pre-industrial levels. The growing levels of emissions have varied, but have been consistent among all greenhouse gases. Emissions in the 2010s averaged 56 billion tons a year, higher than any decade before. Total cumulative emissions from 1870 to 2017 were 425±20 GtC from fossil fuels and industry, and 180±60 GtC from land use change. Land-use change, such as deforestation, caused about 31% of cumulative emissions over 1870–2017, coal 32%, oil 25%, and gas 10%.

Climate justice is an approach to climate action that focuses on the unequal impacts of climate change on marginalized or otherwise vulnerable populations. Climate justice wants to achieve an equitable distribution of both the burdens of climate change and the efforts to mitigate climate change. Climate justice is a type of environmental justice.

Environmental issues in Canada include impacts of climate change, air and water pollution, mining, logging, and the degradation of natural habitats. As one of the world's significant emitters of greenhouse gasses, Canada has the potential to make contributions to curbing climate change with its environmental policies and conservation efforts.

The climate policy of China is to peak its greenhouse gas emissions before 2030 and to be carbon neutral before 2060. Due to the large buildout of solar power in China and burning of coal in China the energy policy of China is closely related to its climate policy. There is also policy to adapt to climate change. Ding Xuexiang represented China at the 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference in 2023, and may be influential in setting climate policy.

Climate debt is the debt said to be owed to developing countries by developed countries for the damage caused by their disproportionately large contributions to climate change. Historical global greenhouse gas emissions, largely by developed countries, pose significant threats to developing countries, who are less able to deal with climate change's negative effects. Therefore, some consider developed countries to owe a debt to developing ones for their disproportionate contributions to climate change.

Reparations are broadly understood as compensation given for an abuse or injury. The colloquial meaning of reparations has changed substantively over the last century. In the early 1900s, reparations were interstate exchanges that were punitive mechanisms determined by treaty and paid by the surrendering side of conflict, such as the World War I reparations paid by Germany and its allies. Reparations are now understood as not only war damages but also compensation and other measures provided to victims of severe human rights violations by the parties responsible. The right of the victim of an injury to receive reparations and the duty of the part responsible to provide them has been secured by the United Nations.

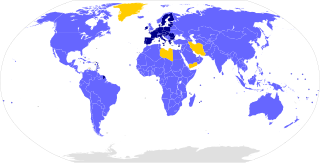

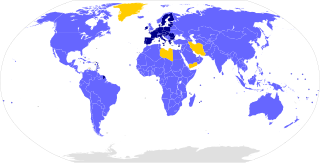

The Paris Agreement, often referred to as the Paris Accords or the Paris Climate Accords, is an international treaty on climate change. Adopted in 2015, the agreement covers climate change mitigation, adaptation, and finance. The Paris Agreement was negotiated by 196 parties at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference near Paris, France. As of February 2023, 195 members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are parties to the agreement. Of the three UNFCCC member states which have not ratified the agreement, the only major emitter is Iran. The United States withdrew from the agreement in 2020, but rejoined in 2021.

Climate change has resulted in an increase in temperature of 2.3 °C (2022) in Europe compared to pre-industrial levels. Europe is the fastest warming continent in the world. Europe's climate is getting warmer due to anthropogenic activity. According to international climate experts, global temperature rise should not exceed 2 °C to prevent the most dangerous consequences of climate change; without reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, this could happen before 2050. Climate change has implications for all regions of Europe, with the extent and nature of impacts varying across the continent.

Loss and damage is a concept to describe results from the adverse effects of climate change and how to deal with them. There has been slow progress on implementing mitigation and adaptation. Some losses and damages are already occurring, and further loss and damage is unavoidable. There is a distinction between economic losses and non-economic losses. The main difference between the two is that non-economic losses involve things that are not commonly traded in markets.

The United Nations Climate Change Conferences are yearly conferences held in the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). They serve as the formal meeting of the UNFCCC parties – the Conference of the Parties (COP) – to assess progress in dealing with climate change, and beginning in the mid-1990s, to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol to establish legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Starting in 2005 the conferences have also served as the "Conference of the Parties Serving as the Meeting of Parties to the Kyoto Protocol" (CMP); also parties to the convention that are not parties to the protocol can participate in protocol-related meetings as observers. From 2011 to 2015 the meetings were used to negotiate the Paris Agreement as part of the Durban platform, which created a general path towards climate action. Any final text of a COP must be agreed by consensus.

A carbon budget is a concept used in climate policy to help set emissions reduction targets in a fair and effective way. It examines the "maximum amount of cumulative net global anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions that would result in limiting global warming to a given level". It can be expressed relative to the pre-industrial period. In this case, it is the total carbon budget. Or it can be expressed from a recent specified date onwards. In that case it is the remaining carbon budget.

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, more commonly referred to as COP26, was the 26th United Nations Climate Change conference, held at the SEC Centre in Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom, from 31 October to 13 November 2021. The president of the conference was UK cabinet minister Alok Sharma. Delayed for a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the third meeting of the parties to the 2015 Paris Agreement, and the 16th meeting of the parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP16).

Climate change in the Marshall Islands is a major issue for the country. As with many countries made up of low-lying islands, the Marshall Islands is highly vulnerable to sea level rise and other impacts of climate change. The atoll and capital city of Majuro are particularly vulnerable, and the issue poses significant implications for the country's population. These threats have prompted Marshallese political leaders to make climate change a key diplomatic issue, who have responded with initiatives such as the Majuro Declaration.

A climate target, climate goal or climate pledge is a measurable long-term commitment for climate policy and energy policy with the aim of limiting the climate change. Researchers within, among others, the UN climate panel have identified probable consequences of global warming for people and nature at different levels of warming. Based on this, politicians in a large number of countries have agreed on temperature targets for warming, which is the basis for scientifically calculated carbon budgets and ways to achieve these targets. This in turn forms the basis for politically decided global and national emission targets for greenhouse gases, targets for fossil-free energy production and efficient energy use, and for the extent of planned measures for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

The 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference or Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, more commonly referred to as COP27, was the 27th United Nations Climate Change conference, held from 6 November until 20 November 2022 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. It took place under the presidency of Egyptian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sameh Shoukry, with more than 92 heads of state and an estimated 35,000 representatives, or delegates, of 190 countries attending. It was the fifth climate summit held in Africa, and the first since 2016.

The Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the United Nations (UN) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the sixth in a series of reports which assess scientific, technical, and socio-economic information concerning climate change. Three Working Groups covered the following topics: The Physical Science Basis (WGI); Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (WGII); Mitigation of Climate Change (WGIII). Of these, the first study was published in 2021, the second report February 2022, and the third in April 2022. The final synthesis report was finished in March 2023.

Climate change ethics is a field of study that explores the moral aspects of climate change. Climate change is often studied and addressed by scientists, economists, and policymakers in value neutral ways. However, philosophers such as Stephen M. Gardiner and the scientific authors of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), argue that decisions related to climate change are moral issues and involve value judgment. Climate change involves difficult moral questions relating to global inequality and human development, who bears responsibility for past emissions, as well as the role of future generations, personal responsibility and many more.

Lukas H. Meyer is a German philosopher, academic and author. He is a university professor as well as speaker of the working section Moral and Political Philosophy at the University of Graz.