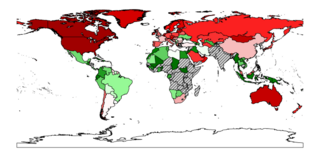

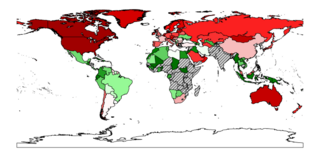

The Kyoto Protocol (Japanese: 京都議定書, Hepburn: Kyōto Giteisho) was an international treaty which extended the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that commits state parties to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, based on the scientific consensus that global warming is occurring and that human-made CO2 emissions are driving it. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in Kyoto, Japan, on 11 December 1997 and entered into force on 16 February 2005. There were 192 parties (Canada withdrew from the protocol, effective December 2012) to the Protocol in 2020.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established an international environmental treaty to combat "dangerous human interference with the climate system", in part by stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. It was signed by 154 states at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), informally known as the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro from 3 to 14 June 1992. Its original secretariat was in Geneva but relocated to Bonn in 1996. It entered into force on 21 March 1994.

The politics of climate change results from different perspectives on how to respond to climate change. Global warming is driven largely by the emissions of greenhouse gases due to human economic activity, especially the burning of fossil fuels, certain industries like cement and steel production, and land use for agriculture and forestry. Since the Industrial Revolution, fossil fuels have provided the main source of energy for economic and technological development. The centrality of fossil fuels and other carbon-intensive industries has resulted in much resistance to climate friendly policy, despite widespread scientific consensus that such policy is necessary.

Ecological debt refers to the accumulated debt seen by some campaigners as owed by the Global North to Global South countries, due to the net sum of historical environmental injustice, especially through resource exploitation, habitat degradation, and pollution by waste discharge. The concept was coined by Global Southerner non-governmental organizations in the 1990s and its definition has varied over the years, in several attempts of greater specification.

Contraction and Convergence (C&C) is a proposed global framework for reducing greenhouse gas emissions to combat climate change. Conceived by the Global Commons Institute (GCI) in the early 1990s, the Contraction and Convergence strategy consists of reducing overall emissions of greenhouse gases to a safe level (contraction), resulting from every country bringing its emissions per capita to a level which is equal for all countries (convergence).

Post-Kyoto negotiations refers to high level talks attempting to address global warming by limiting greenhouse gas emissions. Generally part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), these talks concern the period after the first "commitment period" of the Kyoto Protocol, which expired at the end of 2012. Negotiations have been mandated by the adoption of the Bali Road Map and Decision 1/CP.13.

Climate justice is a term that recognizes "although global warming is a global crisis, its effects are not felt evenly around the world". Climate justice is a faction of environmental justice and focuses on the equitable distribution of the burdens of climate change and the efforts to mitigate them. It has been described as encompassing "a set of rights and obligations, which corporations, individuals and governments have towards those vulnerable people who will be in a way significantly disproportionately affected by climate change."

After the 2007 United Nations Climate Change Conference held on the island of Bali in Indonesia in December 2007, the participating nations adopted the Bali Road Map as a two-year process working towards finalizing a binding agreement at the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark. The conference encompassed meetings of several bodies, including the 13th session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the third session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol.

The 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference, commonly known as the Copenhagen Summit, was held at the Bella Center in Copenhagen, Denmark, between 7 and 18 December. The conference included the 15th session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 5th session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol. According to the Bali Road Map, a framework for climate change mitigation beyond 2012 was to be agreed there.

The Copenhagen Accord is a document which delegates at the 15th session of the Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed to "take note of" at the final plenary on 18 December 2009.

The 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference was held in Cancún, Mexico, from 29 November to 10 December 2010. The conference is officially referred to as the 16th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 16) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 6th session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties (CMP 6) to the Kyoto Protocol. In addition, the two permanent subsidiary bodies of the UNFCCC — the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) — held their 33rd sessions. The 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference extended the mandates of the two temporary subsidiary bodies, the Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP) and the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention (AWG-LCA), and they met as well.

Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA) refers to a set of policies and actions that countries undertake as part of a commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The term recognizes that different countries may take different nationally appropriate action on the basis of equity and in accordance with common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. It also emphasizes financial assistance from developed countries to developing countries to reduce emissions.

Greenhouse Development Rights (GDRs) is a justice-based effort-sharing framework designed to show how the costs of rapid climate stabilization can be shared fairly, among all countries. More precisely, GDRs seeks to transparently calculate national “fair shares” in the costs of an emergency global climate mobilization, in a manner that takes explicit account of the fact that, as things now stand, global political and economic life is divided along both North/South and rich/poor lines.

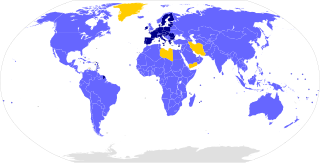

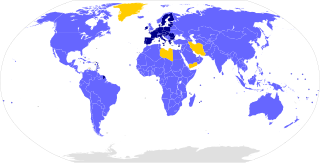

The Paris Agreement, often referred to as the Paris Accords or the Paris Climate Accords, is an international treaty on climate change. Adopted in 2015, the agreement covers climate change mitigation, adaptation, and finance. The Paris Agreement was negotiated by 196 parties at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference near Paris, France. As of February 2023, 195 members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are parties to the agreement. Of the three UNFCCC member states which have not ratified the agreement, the only major emitter is Iran. The United States withdrew from the agreement in 2020, but rejoined in 2021.

The Green Climate Fund (GCF) is a fund established within the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as an operating entity of the Financial Mechanism to assist developing countries in adaptation and mitigation practices to counter climate change. The GCF is based in Incheon, South Korea. It is governed by a Board of 24 members and supported by a Secretariat.

Climate finance are funding processes for investments related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. The term has been used in a narrower sense to refer to transfers of public resources from developed to developing countries, in light of their UN Climate Convention obligations to provide "new and additional financial resources". In a wider sense, the term refers to all financial flows relating to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Loss and damage is a concept to describe results from the adverse effects of climate change and how to deal with them. The appropriate response by governments to loss and damage has been disputed since the UNFCCC's adoption of the term and concept. Establishing liability and compensation for loss and damage has been a long-standing goal for vulnerable and developing countries in the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the Least Developed Countries Group in negotiations. However, developed countries have resisted this. The present UNFCCC mechanism to address loss and damage, the "Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage", focuses on research and dialogue rather than liability or compensation.

The United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP19 or CMP9 was held in Warsaw, Poland from 11 to 23 November 2013. This is the 19th yearly session of the Conference of the Parties to the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 9th session of the Meeting of the Parties to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. The conference delegates continue the negotiations towards a global climate agreement. UNFCCC's Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres and Poland's Minister of the Environment Marcin Korolec led the negotiations.

The United Nations Climate Change Conferences are yearly conferences held in the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). They serve as the formal meeting of the UNFCCC parties – the Conference of the Parties (COP) – to assess progress in dealing with climate change, and beginning in the mid-1990s, to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol to establish legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Starting in 2005 the conferences have also served as the "Conference of the Parties Serving as the Meeting of Parties to the Kyoto Protocol" (CMP); also parties to the convention that are not parties to the protocol can participate in protocol-related meetings as observers. From 2011 to 2015 the meetings were used to negotiate the Paris Agreement as part of the Durban platform, which created a general path towards climate action. Any final text of a COP must be agreed by consensus.

A carbon budget is a concept used in climate policy to help set emissions reduction targets in a fair and effective way. It looks at "the maximum amount of cumulative net global anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions that would result in limiting global warming to a given level". When expressed relative to the pre-industrial period it is referred to as the total carbon budget, and when expressed from a recent specified date it is referred to as the remaining carbon budget.