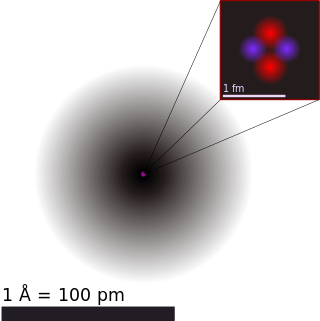

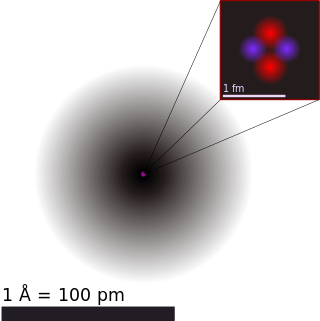

An atom is a particle that consists of a nucleus of protons and neutrons surrounded by an electromagnetically-bound cloud of electrons. The atom is the basic particle of the chemical elements, and the chemical elements are distinguished from each other by the number of protons that are in their atoms. For example, any atom that contains 11 protons is sodium, and any atom that contains 29 protons is copper. The number of neutrons defines the isotope of the element.

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interactions of atoms and molecules. Electromagnetism can be thought of as a combination of electrostatics and magnetism, two distinct but closely intertwined phenomena. Electromagnetic forces occur between any two charged particles, causing an attraction between particles with opposite charges and repulsion between particles with the same charge, while magnetism is an interaction that occurs exclusively between charged particles in relative motion. These two effects combine to create electromagnetic fields in the vicinity of charged particles, which can accelerate other charged particles via the Lorentz force. At high energy, the weak force and electromagnetic force are unified as a single electroweak force.

Electric charge is the physical property of matter that causes it to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be positive or negative. Like charges repel each other and unlike charges attract each other. An object with no net charge is referred to as electrically neutral. Early knowledge of how charged substances interact is now called classical electrodynamics, and is still accurate for problems that do not require consideration of quantum effects.

In physics, the fundamental interactions or fundamental forces are the interactions that do not appear to be reducible to more basic interactions. There are four fundamental interactions known to exist:

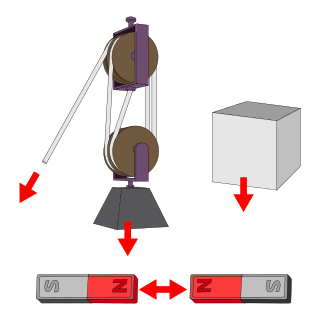

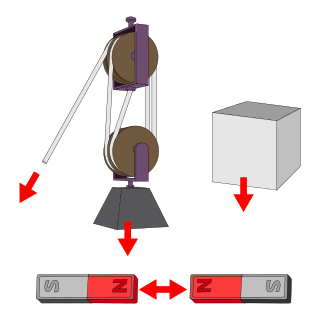

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an object to change its velocity, i.e., to accelerate, unless counterbalanced by other forces. The concept of force makes the everyday notion of pushing or pulling mathematically precise. Because the magnitude and direction of a force are both important, force is a vector quantity. The SI unit of force is the newton (N), and force is often represented by the symbol F.

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

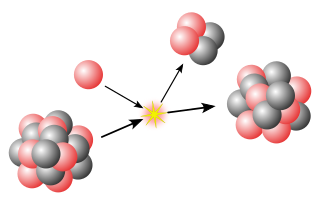

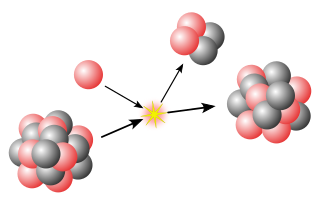

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

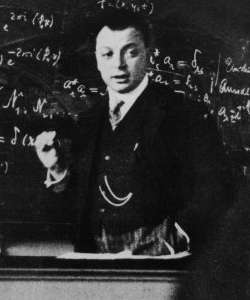

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli exclusion principle states that two or more identical particles with half-integer spins cannot occupy the same quantum state within a quantum system simultaneously. This principle was formulated by Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli in 1925 for electrons, and later extended to all fermions with his spin–statistics theorem of 1940.

In physics, a state of matter is one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist. Four states of matter are observable in everyday life: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. Many intermediate states are known to exist, such as liquid crystal, and some states only exist under extreme conditions, such as Bose–Einstein condensates and Fermionic condensates, neutron-degenerate matter, and quark–gluon plasma. For a complete list of all exotic states of matter, see the list of states of matter.

In molecular physics and chemistry, the van der Waals force is a distance-dependent interaction between atoms or molecules. Unlike ionic or covalent bonds, these attractions do not result from a chemical electronic bond; they are comparatively weak and therefore more susceptible to disturbance. The van der Waals force quickly vanishes at longer distances between interacting molecules.

Degenerate matter occurs when the Pauli exclusion principle significantly alters a state of matter at low temperature. The term is used in astrophysics to refer to dense stellar objects such as white dwarfs and neutron stars, where thermal pressure alone is not enough to avoid gravitational collapse. The term also applies to metals in the Fermi gas approximation.

Electrostatic induction, also known as "electrostatic influence" or simply "influence" in Europe and Latin America, is a redistribution of electric charge in an object that is caused by the influence of nearby charges. In the presence of a charged body, an insulated conductor develops a positive charge on one end and a negative charge on the other end. Induction was discovered by British scientist John Canton in 1753 and Swedish professor Johan Carl Wilcke in 1762. Electrostatic generators, such as the Wimshurst machine, the Van de Graaff generator and the electrophorus, use this principle. See also Stephen Gray in this context. Due to induction, the electrostatic potential (voltage) is constant at any point throughout a conductor. Electrostatic induction is also responsible for the attraction of light nonconductive objects, such as balloons, paper or styrofoam scraps, to static electric charges. Electrostatic induction laws apply in dynamic situations as far as the quasistatic approximation is valid.

In mechanics, the normal force is the component of a contact force that is perpendicular to the surface that an object contacts, as in Figure 1. In this instance normal is used in the geometric sense and means perpendicular, as opposed to the common language use of normal meaning "ordinary" or "expected". A person standing still on a platform is acted upon by gravity, which would pull them down towards the Earth's core unless there were a countervailing force from the resistance of the platform's molecules, a force which is named the "normal force".

Quantum mechanics is the study of matter and its interactions with energy on the scale of atomic and subatomic particles. By contrast, classical physics explains matter and energy only on a scale familiar to human experience, including the behavior of astronomical bodies such as the moon. Classical physics is still used in much of modern science and technology. However, towards the end of the 19th century, scientists discovered phenomena in both the large (macro) and the small (micro) worlds that classical physics could not explain. The desire to resolve inconsistencies between observed phenomena and classical theory led to a revolution in physics, a shift in the original scientific paradigm: the development of quantum mechanics.

In physics the term exchange force has been used to describe two distinct concepts which should not be confused.

When two objects touch, only a certain portion of their surface areas will be in contact with each other. This area of true contact, most often constitutes only a very small fraction of the apparent or nominal contact area. In relation to two contacting objects, the contact area is the part of the nominal area that consists of atoms of one object in true contact with the atoms of the other object. Because objects are never perfectly flat due to asperities, the actual contact area is usually much less than the contact area apparent on a macroscopic scale. Contact area may depend on the normal force between the two objects due to deformation.

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance with mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic particles, and in everyday as well as scientific usage, matter generally includes atoms and anything made up of them, and any particles that act as if they have both rest mass and volume. However it does not include massless particles such as photons, or other energy phenomena or waves such as light or heat. Matter exists in various states. These include classical everyday phases such as solid, liquid, and gas – for example water exists as ice, liquid water, and gaseous steam – but other states are possible, including plasma, Bose–Einstein condensates, fermionic condensates, and quark–gluon plasma.

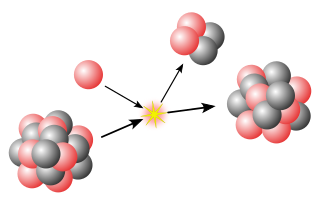

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron in 1932, models for a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons were quickly developed by Dmitri Ivanenko and Werner Heisenberg. An atom is composed of a positively charged nucleus, with a cloud of negatively charged electrons surrounding it, bound together by electrostatic force. Almost all of the mass of an atom is located in the nucleus, with a very small contribution from the electron cloud. Protons and neutrons are bound together to form a nucleus by the nuclear force.

This glossary of physics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to physics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields, including mechanics, materials science, nuclear physics, particle physics, and thermodynamics. For more inclusive glossaries concerning related fields of science and technology, see Glossary of chemistry terms, Glossary of astronomy, Glossary of areas of mathematics, and Glossary of engineering.