Related Research Articles

The Great Vowel Shift was a series of changes in the pronunciation of the English language that took place primarily between 1400 and 1700, beginning in southern England and today having influenced effectively all dialects of English. Through this vowel shift, the pronunciation of all Middle English long vowels were changed. Some consonant sounds also changed, particularly those that became silent; the term Great Vowel Shift is sometimes used to include these consonantal changes.

Maltese is a Semitic language derived from late medieval Sicilian Arabic with Romance superstrata spoken by the Maltese people. It is the national language of Malta and the only official Semitic and Afroasiatic language of the European Union. Maltese is a Latinised variety of spoken historical Arabic through its descent from Siculo-Arabic, which developed as a Maghrebi Arabic dialect in the Emirate of Sicily between 831 and 1091. As a result of the Norman invasion of Malta and the subsequent re-Christianization of the islands, Maltese evolved independently of Classical Arabic in a gradual process of latinisation. It is therefore exceptional as a variety of historical Arabic that has no diglossic relationship with Classical or Modern Standard Arabic. Maltese is thus classified separately from the 30 varieties constituting the modern Arabic macrolanguage. Maltese is also distinguished from Arabic and other Semitic languages since its morphology has been deeply influenced by Romance languages, namely Italian and Sicilian.

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family.

A diphthong, also known as a gliding vowel, is a combination of two adjacent vowel sounds within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: that is, the tongue moves during the pronunciation of the vowel. In most varieties of English, the phrase "no highway cowboy" has five distinct diphthongs, one in every syllable.

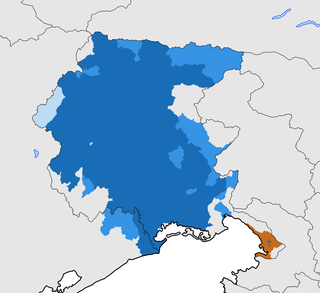

Friulian or Friulan is a Romance language belonging to the Rhaeto-Romance family, spoken in the Friuli region of northeastern Italy. Friulian has around 600,000 speakers, the vast majority of whom also speak Italian. It is sometimes called Eastern Ladin since it shares the same roots as Ladin, but over the centuries, it has diverged under the influence of surrounding languages, including German, Italian, Venetian, and Slovene. Documents in Friulian are attested from the 11th century and poetry and literature date as far back as 1300. By the 20th century, there was a revival of interest in the language.

A digraph or digram is a pair of characters used in the orthography of a language to write either a single phoneme, or a sequence of phonemes that does not correspond to the normal values of the two characters combined.

The Maltese alphabet is based on the Latin alphabet with the addition of some letters with diacritic marks and digraphs. It is used to write the Maltese language, which evolved from the otherwise extinct Siculo-Arabic dialect, as a result of 800 years of independent development. It contains 30 letters: 24 consonants and 6 vowels.

Senglea, also known by its title Città Invicta, is a fortified city in the South Eastern Region of Malta. It is one of the Three Cities in the Grand Harbour area, the other two being Cospicua and Vittoriosa, and has a population of approximately 2,720 people. The city's title Città Invicta was given because it managed to resist the Ottoman invasion at the Great Siege of Malta in 1565. The name Senglea comes from the Grand Master who built it Claude de la Sengle and gave the city a part of his name. While Senglea is the 52nd most populated locality on the island, due to its incredibly small land area, it is the 2nd most densely populated locality after Sliema.

Tunisian Arabic, or simply Tunisian, is a variety of Arabic spoken in Tunisia. It is known among its 12 million speakers as Tūnsi, "Tunisian" or Derja to distinguish it from Modern Standard Arabic, the official language of Tunisia. Tunisian Arabic is mostly similar to eastern Algerian Arabic and western Libyan Arabic.

Jutlandic, or Jutish, is the western variety of Danish, spoken on the peninsula of Jutland in Denmark.

Irish orthography is the set of conventions used to write Irish. A spelling reform in the mid-20th century led to An Caighdeán Oifigiúil, the modern standard written form used by the Government of Ireland, which regulates both spelling and grammar. The reform removed inter-dialectal silent letters, simplified some letter sequences, and modernised archaic spellings to reflect modern pronunciation, but it also removed letters pronounced in some dialects but not in others.

In an alphabetic writing system, a silent letter is a letter that, in a particular word, does not correspond to any sound in the word's pronunciation. In linguistics, a silent letter is often symbolised with a null sign U+2205∅EMPTY SET. Null is an unpronounced or unwritten segment. The symbol resembles the Scandinavian letter Ø and other symbols.

The Three Cities is a collective description of the three fortified cities of Vittoriosa, Senglea and Cospicua in Malta. The oldest of the Three Cities is Vittoriosa, which has existed since prior to the Middle Ages. The other two cities, Senglea and Cospicua, were both founded by the Order of Saint John in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Three Cities are enclosed by the Cottonera Lines, along with several other fortifications. The term Cottonera is synonymous with the Three Cities, although it is sometimes taken to also include the nearby town of Kalkara.

Like many other languages, English has wide variation in pronunciation, both historically and from dialect to dialect. In general, however, the regional dialects of English share a largely similar phonological system. Among other things, most dialects have vowel reduction in unstressed syllables and a complex set of phonological features that distinguish fortis and lenis consonants.

Gh is a digraph found in many languages.

The modern Corsican alphabet uses twenty-two basic letters taken from the Latin alphabet with some changes, plus some multigraphs. The pronunciations of the English, French, Italian or Latin forms of these letters are not a guide to their pronunciation in Corsican, which has its own pronunciation, often the same, but frequently not. As can be seen from the table below, two of the phonemic letters are represented as trigraphs, plus some other digraphs. Nearly all the letters are allophonic; that is, a phoneme of the language might have more than one pronunciation and be represented by more than one letter. The exact pronunciation depends mainly on word order and usage and is governed by a complex set of rules, variable to some degree by dialect. These have to be learned by the speaker of the language.

This article describes the phonology of the Occitan language.

Middle English phonology is necessarily somewhat speculative, since it is preserved only as a written language. Nevertheless, there is a very large text corpus of Middle English. The dialects of Middle English vary greatly over both time and place, and in contrast with Old English and Modern English, spelling was usually phonetic rather than conventional. Words were generally spelled according to how they sounded to the person writing a text, rather than according to a formalised system that might not accurately represent the way the writer's dialect was pronounced, as Modern English is today.

This article explains the phonology of Malay and Indonesian based on the pronunciation of Standard Malay, which is the official language of Brunei, Singapore and Malaysia, and Indonesian, which is the official language of Indonesia and a working language in Timor Leste. There are two main standards for Malay pronunciation, the Johor-Riau standard, used in Brunei and Malaysia, and the Baku, used in Indonesia and Singapore.

References

- ↑ Martine Vanhove, « De quelques traits prehilaliens en maltais », in: Peuplement et arabisation au Maghreb cccidental : dialectologie et histoire, Casa Velazquez - Universidad de Zaragoza (1998), pp.97-108

- ↑ Sciriha, Lydia (1997). Id-djalett tal-Kottonera: analizi socjolingwistika (in Maltese). Daritama Publications. ISBN 978-99909-68-26-2.

- ↑ "Linguistic lustre - The Malta Independent". www.independent.com.mt. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ↑ "Il-Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ilsien Malti". www.kunsilltalmalti.gov.mt. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ Camilleri, Saviour (2010). "Dwardu Cachia – Kittieb Senglean (1858–1907)" (PDF). Marija Bambina Senglea Festa 2010.

- ↑ Vella, Olvin; Mifsud, Manwel (2006). Kollu Malti: program 9 (in Maltese). L-Università ta' Malta.

- ↑ "Il-Birgu". Malti. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ↑ "Isma'". Malti. Retrieved 19 January 2023.