Anarcho-capitalism is an anti-statist, libertarian political philosophy and economic theory that seeks to abolish centralized states in favor of stateless societies with systems of private property enforced by private agencies, based on concepts such as the non-aggression principle, free markets and self-ownership. Anarcho-capitalist philosophy extends the concept of ownership to include control of private property as part of the self, and, in some cases, control of other people as private property. In the absence of statute, anarcho-capitalists hold that society tends to contractually self-regulate and civilize through participation in the free market, which they describe as a voluntary society involving the voluntary exchange of goods and services. In a theoretical anarcho-capitalist society the system of private property would still exist, as it would be enforced by private defense agencies and/or insurance companies selected by property owners, whose ownership rights or claims would be enforced by private defence agencies and/or insurance companies. These agencies or companies would operate competitively in a market and fulfill the roles of courts and the police, similar to a state apparatus. Some anarcho-capitalist authors have argued that slavery is compatible with anarcho-capitalist ideals.

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, economic freedom, political freedom and freedom of speech. Classical liberalism, contrary to liberal branches like social liberalism, looks more negatively on social policies, taxation and the state involvement in the lives of individuals, and it advocates deregulation.

Gustave de Molinari was a Belgian political economist and French Liberal School theorist associated with French laissez-faire economists such as Frédéric Bastiat and Hippolyte Castille.

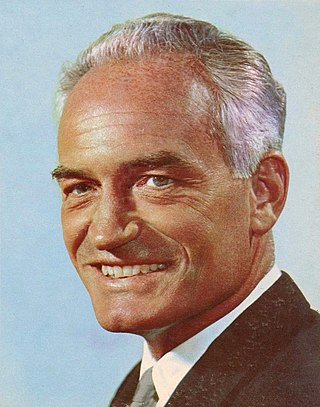

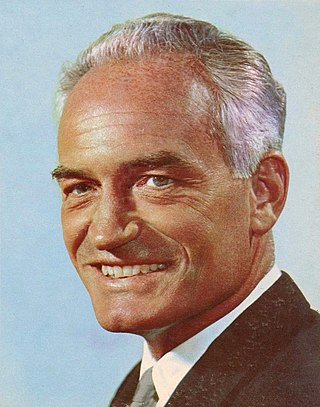

Murray Newton Rothbard was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian movement, particularly its right-wing strands, and was a founder and leading theoretician of anarcho-capitalism. He wrote over twenty books on political theory, history, economics, and other subjects.

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand. The major characteristic of a market economy is the existence of factor markets that play a dominant role in the allocation of capital and the factors of production.

Lysander Spooner was an American abolitionist, entrepreneur, lawyer, essayist, natural rights legal theorist, pamphletist, political philosopher, Unitarian and writer often associated with the Boston anarchist tradition.

Laissez-faire is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism. As a system of thought, laissez-faire rests on the following axioms: "the individual is the basic unit in society, i.e., the standard of measurement in social calculus; the individual has a natural right to freedom; and the physical order of nature is a harmonious and self-regulating system." The original phrase was laissez faire, laissez passer, with the second part meaning "let (things) pass". It is generally attributed to Vincent de Gournay.

Anarchist economics is the set of theories and practices of economic activity within the political philosophy of anarchism. Many anarchists are anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist, with anarchism usually referred to as a form of libertarian socialism, i.e. a stateless system of socialism. Anarchists support personal property and oppose capital concentration, interest, monopoly, private ownership of productive property such as the means of production, profit, rent, usury and wage slavery which are viewed as inherent to capitalism.

The nature of capitalism is criticized by left-wing anarchists, who reject hierarchy and advocate stateless societies based on non-hierarchical voluntary associations. Anarchism is generally defined as the libertarian philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful as well as opposing authoritarianism, illegitimate authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Capitalism is generally considered by scholars to be an economic system that includes private ownership of the means of production, creation of goods or services for profit or income, the accumulation of capital, competitive markets, voluntary exchange and wage labor, which have generally been opposed by most anarchists historically. Since capitalism is variously defined by sources and there is no general consensus among scholars on the definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category, the designation is applied to a variety of historical cases, varying in time, geography, politics and culture.

The non-aggression principle (NAP), also called the non-aggression axiom, is the philosophical position that states that any person is permitted to do everything with his property except aggression, defined as the initiation of forceful action, which is in turn defined as 'the application or threat of' 'physical interference or fraud ', any of which without consent. The principle is also called the non-initiation of force. The principle incorporates universal enforceability.

Libertarianism is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, emphasizing equality before the law and civil rights to freedom of association, freedom of speech, freedom of thought and freedom of choice. Libertarians are often skeptical of or opposed to authority, state power, warfare, militarism and nationalism, but some libertarians diverge on the scope of their opposition to existing economic and political systems. Various schools of libertarian thought offer a range of views regarding the legitimate functions of state and private power. Different categorizations have been used to distinguish various forms of Libertarianism. Scholars distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital, usually along left–right or socialist–capitalist lines. Libertarians of various schools were influenced by liberal ideas.

In the United States, libertarianism is a political philosophy promoting individual liberty. According to common meanings of conservatism and liberalism in the United States, libertarianism has been described as conservative on economic issues and liberal on personal freedom, often associated with a foreign policy of non-interventionism. Broadly, there are four principal traditions within libertarianism, namely the libertarianism that developed in the mid-20th century out of the revival tradition of classical liberalism in the United States after liberalism associated with the New Deal; the libertarianism developed in the 1950s by anarcho-capitalist author Murray Rothbard, who based it on the anti-New Deal Old Right and 19th-century libertarianism and American individualist anarchists such as Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner while rejecting the labor theory of value in favor of Austrian School economics and the subjective theory of value; the libertarianism developed in the 1970s by Robert Nozick and founded in American and European classical liberal traditions; and the libertarianism associated with the Libertarian Party, which was founded in 1971, including politicians such as David Nolan and Ron Paul.

Right-libertarianism, also known as libertarian capitalism, or right-wing libertarianism, is a libertarian political philosophy that supports capitalist property rights and defends market distribution of natural resources and private property. The term right-libertarianism is used to distinguish this class of views on the nature of property and capital from left-libertarianism, a type of libertarianism that combines self-ownership with an egalitarian approach to property and income. In contrast to socialist libertarianism, right-libertarianism supports free-market capitalism. Like most forms of libertarianism, it supports civil liberties, especially natural law, negative rights, the non-aggression principle, and a major reversal of the modern welfare state.

For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto is a book by American economist and historian Murray Rothbard, in which the author promotes anarcho-capitalism. The work has been credited as an influence on modern libertarian thought and on part of the New Right.

Libertarianism is variously defined by sources as there is no general consensus among scholars on the definition nor on how one should use the term as a historical category. Scholars generally agree that libertarianism refers to the group of political philosophies which emphasize freedom, individual liberty and voluntary association. Libertarians generally advocate a society with little or no government power.

Libertarian conservatism, also referred to as conservative libertarianism and conservatarianism, is a political and social philosophy that combines conservatism and libertarianism, representing the libertarian wing of conservatism and vice versa.

Libertarian anarchism may refer to:

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to libertarianism:

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism, and his writing is generally regarded as representing the economic expression of 19th-century liberalism up until the Great Depression and rise of Keynesianism in the 20th century. Historically, economic liberalism arose in response to feudalism and mercantilism.