X.500 is a series of computer networking standards covering electronic directory services. The X.500 series was developed by the Telecommunication Standardization Sector of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU-T). ITU-T was formerly known as the Consultative Committee for International Telephony and Telegraphy (CCITT). X.500 was first approved in 1988. The directory services were developed to support requirements of X.400 electronic mail exchange and name lookup. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) were partners in developing the standards, incorporating them into the Open Systems Interconnection suite of protocols. ISO/IEC 9594 is the corresponding ISO/IEC identification.

In cryptography and computer security, a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack is a cyberattack where the attacker secretly relays and possibly alters the communications between two parties who believe that they are directly communicating with each other, as the attacker has inserted themselves between the two parties. One example of a MITM attack is active eavesdropping, in which the attacker makes independent connections with the victims and relays messages between them to make them believe they are talking directly to each other over a private connection, when in fact the entire conversation is controlled by the attacker. The attacker must be able to intercept all relevant messages passing between the two victims and inject new ones. This is straightforward in many circumstances; for example, an attacker within the reception range of an unencrypted Wi-Fi access point could insert themselves as a man-in-the-middle. As it aims to circumvent mutual authentication, a MITM attack can succeed only when the attacker impersonates each endpoint sufficiently well to satisfy their expectations. Most cryptographic protocols include some form of endpoint authentication specifically to prevent MITM attacks. For example, TLS can authenticate one or both parties using a mutually trusted certificate authority.

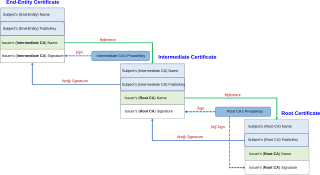

In cryptography, a public key certificate, also known as a digital certificate or identity certificate, is an electronic document used to prove the validity of a public key. The certificate includes information about the key, information about the identity of its owner, and the digital signature of an entity that has verified the certificate's contents. If the signature is valid, and the software examining the certificate trusts the issuer, then it can use that key to communicate securely with the certificate's subject. In email encryption, code signing, and e-signature systems, a certificate's subject is typically a person or organization. However, in Transport Layer Security (TLS) a certificate's subject is typically a computer or other device, though TLS certificates may identify organizations or individuals in addition to their core role in identifying devices. TLS, sometimes called by its older name Secure Sockets Layer (SSL), is notable for being a part of HTTPS, a protocol for securely browsing the web.

In cryptography and computer security, a root certificate is a public key certificate that identifies a root certificate authority (CA). Root certificates are self-signed and form the basis of an X.509-based public key infrastructure (PKI). Either it has matched Authority Key Identifier with Subject Key Identifier, in some cases there is no Authority Key identifier, then Issuer string should match with Subject string. For instance, the PKIs supporting HTTPS for secure web browsing and electronic signature schemes depend on a set of root certificates.

In cryptography, a certificate authority or certification authority (CA) is an entity that stores, signs, and issues digital certificates. A digital certificate certifies the ownership of a public key by the named subject of the certificate. This allows others to rely upon signatures or on assertions made about the private key that corresponds to the certified public key. A CA acts as a trusted third party—trusted both by the subject (owner) of the certificate and by the party relying upon the certificate. The format of these certificates is specified by the X.509 or EMV standard.

Verisign Inc. is an American company based in Reston, Virginia, United States, that operates a diverse array of network infrastructure, including two of the Internet's thirteen root nameservers, the authoritative registry for the .com, .net, and .name generic top-level domains and the .cc country-code top-level domains, and the back-end systems for the .jobs and .edu sponsored top-level domains.

In cryptography, a trusted third party (TTP) is an entity which facilitates interactions between two parties who both trust the third party; the third party reviews all critical transaction communications between the parties, based on the ease of creating fraudulent digital content. In TTP models, the relying parties use this trust to secure their own interactions. TTPs are common in any number of commercial transactions and in cryptographic digital transactions as well as cryptographic protocols, for example, a certificate authority (CA) would issue a digital certificate to one of the two parties in the next example. The CA then becomes the TTP to that certificate's issuance. Likewise transactions that need a third party recordation would also need a third-party repository service of some kind.

CyberTrust was a security services company formed in Virginia in November 2004 from the merger of TruSecure and Betrusted. Betrusted previously acquired GTE Cybertrust. Cybertrust acquired a large stake in Ubizen, a European security services firm based in Belgium, to become one of the largest information security firms in the world. It was acquired by Verizon Business in 2007. In 2015, the CyberTrust root certificates were acquired by DigiCert, Inc., a leading global Certificate Authority (CA) and provider of trusted identity and authentication services.

Thawte Consulting is a certificate authority (CA) for X.509 certificates. Thawte was founded in 1995 by Mark Shuttleworth in South Africa. As of December 30, 2016, its then-parent company, Symantec Group, was collectively the third largest public CA on the Internet with 17.2% market share.

Xcitium, formerly known as Comodo Security Solutions, Inc., is a cybersecurity company headquartered in Bloomfield, New Jersey.

GeoTrust is a digital certificate provider. The GeoTrust brand was bought by Symantec from Verisign in 2010, but agreed to sell the certificate business in August 2017 to private equity and growth capital firm Thoma Bravo LLC. GeoTrust was the first certificate authority to use the domain-validated certificate method which accounts for 70 percent of all SSL certificates on the Internet. By 2006, GeoTrust was the 2nd largest certificate authority in the world with 26.7 percent market share according to independent survey company Netcraft.

Balatarin is a Persian language social and political link-sharing website aimed primarily at Iranian audiences. Balatarin does not generate news in-house but provides a hub where users can post links to webpages of their choice, vote on their relevance or significance, and post comments. New links initially go to the "recently posted" page; as they collect positive votes, they gain a higher rank and move to the front page, which increases their visibility. Combining the technical attributes of reddit, digg, newsvine, and del.icio.us, Balatarin is a mission-oriented platform dedicated to enabling and fostering freedom of expression and information for the benefit of Iranian society.

DigiCert, Inc. is a digital security company headquartered in Lehi, Utah. As a certificate authority (CA) and trusted third party, DigiCert provides public key infrastructure (PKI) and validation required for issuing digital certificates or TLS/SSL certificates.

The Certification Authority Browser Forum, also known as the CA/Browser Forum, is a voluntary consortium of certification authorities, vendors of Internet browser and secure email software, operating systems, and other PKI-enabled applications that promulgates industry guidelines governing the issuance and management of X.509 v.3 digital certificates that chain to a trust anchor embedded in such applications. Its guidelines cover certificates used for the SSL/TLS protocol and code signing, as well as system and network security of certificate authorities.

StartCom was a certificate authority founded in Eilat, Israel, and later based in Beijing, China, that had three main activities: StartCom Enterprise Linux, StartSSL and MediaHost. StartCom set up branch offices in China, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom and Spain. Due to multiple faults on the company's end, all StartCom certificates were removed from Mozilla Firefox in October 2016 and Google Chrome in March 2017, including certificates previously issued, with similar removals from other browsers expected to follow.

DigiD is an identity management platform which government agencies of the Netherlands, including the Tax and Customs Administration and Dienst Uitvoering Onderwijs, can use to verify the identity of Dutch residents on the Internet. In 2015 it was used for 200 million authentications by 12 million citizens. The system is tied to the Dutch national identification number. The system has been mandatory when submitting tax forms electronically since 2006.

Convergence was a proposed strategy for replacing SSL certificate authorities, first put forth by Moxie Marlinspike in August 2011 while giving a talk titled "SSL and the Future of Authenticity" at the Black Hat security conference. It was demonstrated with a Firefox addon and a server-side notary daemon.

Certificate Transparency (CT) is an Internet security standard for monitoring and auditing the issuance of digital certificates.

Let's Encrypt is a non-profit certificate authority run by Internet Security Research Group (ISRG) that provides X.509 certificates for Transport Layer Security (TLS) encryption at no charge. It is the world's largest certificate authority, used by more than 300 million websites, with the goal of all websites being secure and using HTTPS. The Internet Security Research Group (ISRG), the provider of the service, is a public benefit organization. Major sponsors include the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), the Mozilla Foundation, OVH, Cisco Systems, Facebook, Google Chrome, Internet Society, AWS, NGINX, and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Other partners include the certificate authority IdenTrust, the University of Michigan (U-M), and the Linux Foundation.

OneSpan is a publicly traded cybersecurity technology company based in Chicago, Illinois, with offices in Montreal, Brussels and Zurich. The company offers a cloud-based and open-architected anti-fraud platform and is historically known for its multi-factor authentication and electronic signature software.