Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse (trivium) along with grammar and logic/dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or writers use to inform, persuade, and motivate their audiences. Rhetoric also provides heuristics for understanding, discovering, and developing arguments for particular situations.

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilian, although the alternate spellings of Quintillian and Quinctilian are occasionally seen, the latter in older texts.

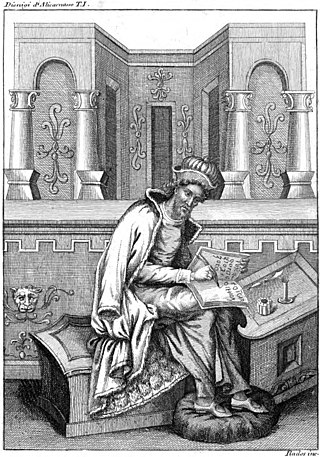

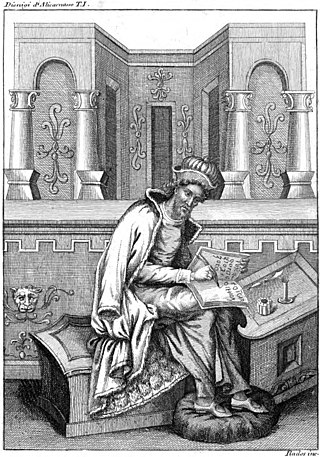

Dionysius of Halicarnassus was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary style was atticistic – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.

Mimesis is a term used in literary criticism and philosophy that carries a wide range of meanings, including imitatio, imitation, nonsensuous similarity, receptivity, representation, mimicry, the act of expression, the act of resembling, and the presentation of the self.

Aristotle's Poetics is the earliest surviving work of Greek dramatic theory and the first extant philosophical treatise to focus on literary theory. In this text Aristotle offers an account of ποιητική, which refers to poetry and more literally "the poetic art," deriving from the term for "poet; author; maker," ποιητής. Aristotle divides the art of poetry into verse drama, lyric poetry, and epic. The genres all share the function of mimesis, or imitation of life, but differ in three ways that Aristotle describes:

- Differences in music rhythm, harmony, meter, and melody.

- Difference of goodness in the characters.

- Difference in how the narrative is presented: telling a story or acting it out.

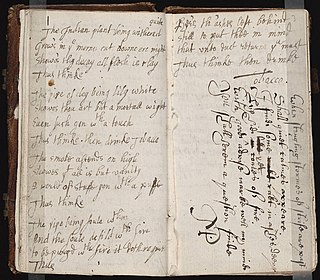

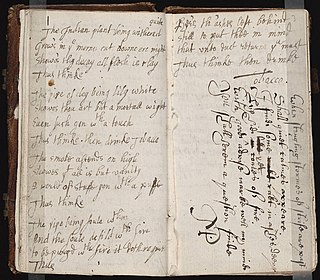

Commonplace books are a way to compile knowledge, usually by writing information into books. They have been kept from antiquity, and were kept particularly during the Renaissance and in the nineteenth century. Such books are similar to scrapbooks filled with items of many kinds: notes, proverbs, adages, aphorisms, maxims, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, prayers, legal formulas, and recipes.

On the Sublime is a Roman-era Greek work of literary criticism dated to the 1st century C.E. Its author is unknown, but is conventionally referred to as Longinus or Pseudo-Longinus. It is regarded as a classic work on aesthetics and the effects of good writing. The treatise highlights examples of good and bad writing from the previous millennium, focusing particularly on what may lead to the sublime.

Jacopo Mazzoni was an Italian philosopher, a professor in Pisa, and friend of Galileo Galilei. His first name is sometimes reported as "Giacomo".

Hermagoras of Temnos was an Ancient Greek rhetorician of the Rhodian school and teacher of rhetoric in Rome, where the Suda states he died at an advanced age.

Memoria was the term for aspects involving memory in Western classical rhetoric. The word is Latin, and can be translated as "memory".

Aristotle's Rhetoric is an ancient Greek treatise on the art of persuasion, dating from the 4th century BCE. The English title varies: typically it is Rhetoric, the Art of Rhetoric, On Rhetoric, or a Treatise on Rhetoric.

Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style is a rhetoric textbook written by Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus, and first published in 1512. It was a best-seller widely used for teaching how to rewrite pre-existing texts, and how to incorporate them in a new composition. Erasmus systematically instructed on how to embellish, amplify, and give variety to speech and writing.

Institutio Oratoria is a twelve-volume textbook on the theory and practice of rhetoric by Roman rhetorician Quintilian. It was published around year 95 AD. The work deals also with the foundational education and development of the orator himself.

Byzantine rhetoric refers to rhetorical theorizing and production during the time of the Byzantine Empire. Byzantine rhetoric is significant in part because of the sheer volume of rhetorical works produced during this period. Rhetoric was the most important and difficult topic studied in the Byzantine education system, beginning at the Pandidakterion in early fifth century Constantinople, where the school emphasized the study of rhetoric with eight teaching chairs, five in Greek and three in Latin. The hard training of Byzantine rhetoric provided skills and credentials for citizens to attain public office in the imperial service, or posts of authority within the Church.

The Rhetoric to Alexander is a treatise traditionally attributed to Aristotle. It is now generally believed to be the work of Anaximenes of Lampsacus.

In classical rhetoric, figures of speech are classified as one of the four fundamental rhetorical operations or quadripartita ratio: addition (adiectio), omission (detractio), permutation (immutatio) and transposition (transmutatio).

Imitation is the doctrine of artistic creativity according to which the creative process should be based on the close imitation of the masterpieces of the preceding authors. This concept was first formulated by Dionysius of Halicarnassus in the first century BCE as imitatio, and has since dominated for almost two thousand years the Western history of the arts and classicism. Plato has regarded imitation as a general principle of art, as he viewed art itself as an imitation of life. This theory was popular and well accepted during the classical period. During the Renaissance period, imitation was seen as a means of obtaining one's personal style; this was alluded to by the artists of that era like Cennino Cennini, Petrarch and Pier Paolo Vergerio. In the 18th century, Romanticism reversed it with the creation of the institution of romantic originality. In the 20th century, the modernist and postmodern movements in turn discarded the romantic idea of creativity, and heightened the practice of imitation, copying, plagiarism, rewriting, appropriation and so on as the central artistic device.

Mimesis criticism is a method of interpreting texts in relation to their literary or cultural models. Mimesis, or imitation (imitatio), was a widely used rhetorical tool in antiquity up until the 18th century's romantic emphasis on originality. Mimesis criticism looks to identify intertextual relationships between two texts that go beyond simple echoes, allusions, citations, or redactions. The effects of imitation are usually manifested in the later text by means of distinct characterization, motifs, and/or plot structure.

On Training for Public Speaking is a short text written by Dio Chrysostom in the late first or early second century AD. The work takes the form of a letter to an anonymous man of affairs who has decided to train as a public speaker. It mostly consists of recommendations of authors for the recipient to read as examples of good style. The text is thus an important source on the formation of the Greek Classical canon in the early Roman empire.