Containerization is a system of intermodal freight transport using intermodal containers. Containerization, also referred as container stuffing or container loading, is the process of unitization of cargoes in exports. Containerization is the predominant form of unitization of export cargoes, as opposed to other systems such as the barge system or palletization. The containers have standardized dimensions. They can be loaded and unloaded, stacked, transported efficiently over long distances, and transferred from one mode of transport to another—container ships, rail transport flatcars, and semi-trailer trucks—without being opened. The handling system is mechanized so that all handling is done with cranes and special forklift trucks. All containers are numbered and tracked using computerized systems.

The 1934 West Coast waterfront strike lasted 83 days, and began on May 9, 1934, when longshoremen in every US West Coast port walked out. Organized by the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA), the strike peaked with the death of two workers on "Bloody Thursday" and the subsequent San Francisco General Strike, which stopped all work in the major port city for four days and led ultimately to the settlement of the West Coast Longshoremen's Strike.

The International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) is a North American labor union representing longshore workers along the East Coast of the United States and Canada, the Gulf Coast, the Great Lakes, Puerto Rico, and inland waterways; on the West Coast, the dominant union is the International Longshore and Warehouse Union. The ILA has approximately 200 local affiliates in port cities in these areas.

Malcom Purcell McLean was an American businessman who invented the modern intermodal shipping container, which revolutionized transport and international trade in the second half of the twentieth century. Containerization led to a significant reduction in the cost of freight transportation by eliminating the need for repeated handling of individual pieces of cargo, and also improved reliability, reduced cargo theft, and cut inventory costs by shortening transit time. Containerization is a major driver of globalization.

Docker most often refers to:

The Battle of Ballantyne Pier occurred in Ballantyne Pier during a docker's strike in Vancouver, British Columbia, in June 1935.

The British Columbia Maritime Employers Association is an association representing the interests of member companies in industrial relations on Vancouver's and other British Columbian seaports.

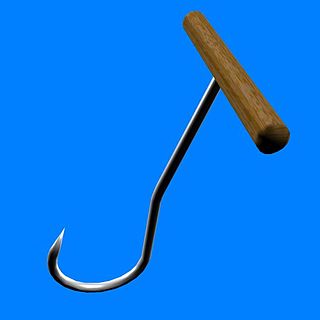

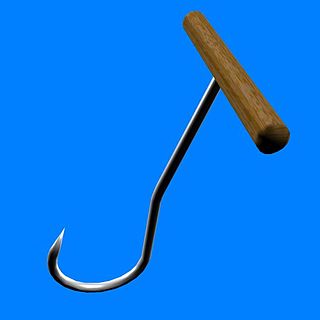

A hook is a hand tool used for securing and moving loads. It consists of a round wooden handle with a strong metal hook about 20 cm long projecting at a right angle from the center of the handle. The appliance is held in a closed fist with the hook projecting between two fingers.

In shipping, break-bulk, breakbulk, or break bulk cargo, also called general cargo, is goods that are stowed on board ships in individually counted units. Traditionally, the large numbers of items are recorded on distinct bills of lading that list them by different commodities. This is in contrast to cargo stowed in modern intermodal containers as well as bulk cargo, which goes directly, unpackaged and in large quantities, into a ship's hold(s), measured by volume or weight.

The Red Hook Marine Terminal is an intermodal freight transport facility in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn in New York City, on the Upper New York Bay in the Port of New York and New Jersey. The maritime facility handles container ships and bulk cargo and includes a container terminal. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) bought the piers in the 1950s when there was still much break bulk cargo activity in the port. The container terminal was built in the 1980s.

Dockworkers in New Orleans at the turn of the 20th century often coordinated their unionization efforts across racial lines. The nature of that coordination has led some scholars to conclude that the seeming interracial union activity was in fact biracial: a well-organized plan of parallel concerted activity with coordination and support between the groups, but with a clear divide along racial lines.

The Waterfront Workers History Project is a program of the University of Washington, which serves to document the history of workers and unions active on the ports, inland waterways, fisheries, canneries, and other waterfront industries of the western United States and Canada, specifically, California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, and British Columbia. In collaboration with the Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights History Projects, and sponsored by the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies, the Project is a collective effort to organize and present historical data covering significant events from 1894 to the current day.

The Mechanization and Modernization (M&M) Agreement of 1960 was an agreement reached by California longshoremen unions: International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA), and the Pacific Maritime Association. This agreement applied to workers on the Pacific Coast of the United States, the West Coast of Canada, and Hawaii. The original agreement was contracted for five years and would be in effect until July 1, 1966.

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) is a labor union which primarily represents dock workers on the West Coast of the United States, Hawaii, and in British Columbia, Canada; on the East Coast, the dominant union is the International Longshoremen's Association. The union was established in 1937 after the 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike, a three-month-long strike that culminated in a four-day general strike in San Francisco, California, and the Bay Area. It disaffiliated from the AFL–CIO on August 30, 2013.

Swanson Dock is an international shipping facility in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It was constructed between 1966 and 1972 by the Melbourne Harbor Trust, leading off the north bank of the Yarra River, to alleviate congestion in the port and provide Melbourne's first container shipping terminal. It is located about 2 km downstream from the Melbourne CBD and was named after Victor Swanson, chairman of the Melbourne Harbor Trust from 1960 to 1972.

On July 1, 1971, members of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) walked out against their employers, represented by the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA). The union's goal was to secure employment, wages, and benefits in the face of increased mechanization, shrinking workforce, and the slowing economic climate of the early 1970s. The strike shut down all 56 West coast ports, including those in Canada, and lasted 130 days, the longest strike in the ILWU's history.

The Longshore Strike 1948 was an industrial dispute which took place in 1948 on the west coast of the United States. President of the ILWU at the time was Harry Bridges. The WEA led by Frank P. Foisie were in a conflict, they were unable to come to agreeable terms and with the issues of hiring and the politics of union leadership, longshoremen and marine unions performed a walk out on September 2, 1948.

The strike shut down the United States’ West Coast ports and put a dent in American labor history and a positive change for future longshoremen.

The Portland Waterfront strike of 1922 was a labor strike conducted by the International Longshoremen's Association which took place in Portland, Oregon from late April to late June 1922. The strike was ineffective at closing down the Port of Portland due to strikebreakers, and on June 22 the strike ended with the employers dictating terms.

In the late 1870s, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh communities on the North Shore of Burrard Inlet experienced an increase of physical and economic encroachment from the expansion of neighbouring Vancouver. Faced with urbanization and industrialization around reserve lands, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh traditional economies became increasingly marginalized, while government-imposed laws increasingly restricted Native fishing, hunting, and access to land and waters for subsistence. In response, these communities increasingly turned to participating in the wage-labor economy.

The Portland Longshoremans Benevolent Society was a trade union and benevolent society in Portland, Maine, United States. It existed as an independent organization from its founding in 1880 until it affiliated with the International Longshoremen's Association in 1914. Incorporated in 1880, it was composed of primarily Irish and Irish-American dockworkers who loaded and unloaded ships in the Portland waterfront. The early peak of PLSBS membership occurred in 1899 when the union had 868 members. By 1910, declines in the amount of Canadian grain exported through the port meant decreased membership, which hit 425. Having been defeated in two major strikes, the PLSBS affiliated with the International Longshoremen's Association in early 1914. Similar independent unions had recently joined the ILA in Boston and elsewhere.