The Royal National Park is a protected national park that is located in Sutherland Shire local government area in the southern portion of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Sclerophyll is a type of vegetation that is adapted to long periods of dryness and heat. The plants feature hard leaves, short internodes and leaf orientation which is parallel or oblique to direct sunlight. The word comes from the Greek sklēros (hard) and phyllon (leaf). The term was coined by A.F.W. Schimper in 1898, originally as a synonym of xeromorph, but the two words were later differentiated.

The geography of Sydney is characterised by its coastal location on a basin bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the east, the Blue Mountains to the west, the Hawkesbury River to the north and the Woronora Plateau to the south. Sydney lies on a submergent coastline on the east coast of New South Wales, where the ocean level has risen to flood deep river valleys (rias) carved in the Sydney sandstone. Port Jackson, better known as Sydney Harbour, is one such ria.

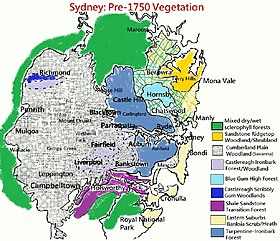

The Cumberland Plain, also known as Cumberland Basin, is a relatively flat region lying to the west of Sydney CBD in New South Wales, Australia. An IBRA biogeographic region, Cumberland Basin is the preferred physiographic and geological term for the low-lying plain of the Permian-Triassic Sydney Basin found between Sydney and the Blue Mountains, and it is a structural sub-basin of the Sydney Basin.

Eucalyptus botryoides, commonly known as the bangalay, bastard jarrah, woollybutt or southern mahogany, is a small to tall tree native to southeastern Australia. Reaching up to 40 metres high, it has rough bark on its trunk and branches. It is found on sandstone- or shale-based soils in open woodland, or on more sandy soils behind sand dunes. The white flowers appear in summer and autumn. It reproduces by resprouting from its woody lignotuber or epicormic buds after bushfire. E. botryoides hybridises with the Sydney blue gum in the Sydney region. The hard, durable wood has been used for panelling and flooring.

The Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (STIF) is a wet sclerophyll forest community of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, that is typically found in the Inner West and Northern region of Sydney. It is also among the three of these plant communities which have been classified as Endangered, under the New South Wales government's Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, with only around 0.5% of its original pre-settlement range remaining.

The Eastern Australian temperate forests is a broad ecoregion of open forest on uplands starting from the east coast of New South Wales in the South Coast to southern Queensland, Australia. Although dry sclerophyll and wet sclerophyll eucalyptus forests predominate within this ecoregion, a number of distinguishable rainforest communities are present as well.

Dichelachne crinita , commonly known as the longhair plume grass, is a type of grass found in Australia, New Zealand and islands of the Pacific Ocean. It is often seen on sandy soils near the sea as well as woodlands. The flowering panicles are open and feathery at maturity. The grass may grow up to 1.5 metres (5 ft) tall. Crinita, the specific epithet, is derived from Latin (hairy).

Western Sydney Regional Park is a large urban park and a nature reserve situated in Western Sydney, Australia within the suburbs of Horsley Park and Abbotsbury. A precinct of Western Sydney Parklands, a park system, and situated within the heart of the Cumberland Plain Woodland, the regional park features several picnic areas, recreational facilities, equestrian trails, and walking paths within the Australian bush.

The Dharawal National Park is a protected national park that is located in the Illawarra region of New South Wales, in eastern Australia. The 6,508-hectare (16,080-acre) national park is situated between the Illawarra Range and the Georges River and is approximately 45 kilometres (28 mi) south west of Sydney. There are three entry points to the park: from the east through Darkes Forest; from the north through Wedderburn; and from the south through Appin.

The Cooks River/Castlereagh Ironbark Forest (CRCIF) is a scattered, dry sclerophyll, open-forest to low woodland and scrubland which occurs predominantly in the Cumberland subregion of the Sydney basin bioregion, between Castlereagh and Holsworthy, as well as around the headwaters of the Cooks River. The Cooks River Clay Plain Scrub Forest is a component of this ecological community, though both belong to a larger occurring community called the Temperate Eucalyptus fibrosa/Melaleuca decora woodland.

The Cumberland Plain Woodland, also known as Cumberland Plain Bushland and Western Sydney woodland, is a grassy woodland community found predominantly in Western Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, that comprises an open tree canopy, a groundcover with grasses and herbs, usually with layers of shrubs and/or small trees.

The Sydney Sandstone Ridgetop Woodland, also known as Coastal Sandstone Ridgetop Woodland and Hornsby Enriched Sandstone Exposed Woodland, is a shrubby woodland and mallee community situated in northern parts of Sydney, Australia, where it is found predominantly on ridgetops and slopes of the Hornsby Plateau, Woronora Plateau and the lower Blue Mountains area. It is an area of high biodiversity, existing on poor sandstone soils, with regular wildfires, and moderate rainfall.

Wide Bay Military Reserve is a heritage-listed military installation at Tin Can Bay Road, Tin Can Bay, Queensland, Australia. The reserve supports a diverse range of plant communities from estuarine, strand, wetlands, heath, tall shrublands and woodlands, to the open forests of the sub-coastal hills and ranges. The total number of bird species recorded for the place totals 250, which is high by Australian standards. It was added to the Australian Commonwealth Heritage List on 22 June 2004.

The Southeast Australia temperate forests is a temperate broadleaf and mixed forests ecoregion of south-eastern Australia. It includes the temperate lowland forests of southeastern Australia, at the southern end of the Great Dividing Range. Vegetation ranges from wet forests along the coast to dry forests and woodlands inland.

The Shale Sandstone Transition Forest, also known as Cumberland Shale-Sandstone Ironbark Forest, is a transitory ecotone between the grassy woodlands of the Cumberland Plain Woodlands and the dry sclerophyll forests of the sandstone plateaus on the edges of the Cumberland Plain in Sydney, Australia.

The Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub, which also incorporates Sydney Coastal Heaths, is a remnant sclerophyll scrubland and heathland that is found in the eastern and southern regions of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 as and endangered vegetation community and as 'critically endangered' under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, the Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub is found on ancient, nutrient poor sands either on dunes or on promontories. Sydney coastal heaths are a scrubby heathland found on exposed coastal sandstone plateau in the south.

The Castlereagh Scribbly Gum and Agnes Banks Woodlands is an endangered sclerophyll low-woodland and shrubland community found in western Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Vegetation comprises low woodlands with sclerophyllous shrubs and an uneven ground layer of graminoids and forbs.

The Swan Coastal Plain Shrublands and Woodlands is a sclerophyll-woodland vegetation community that stretch from Kalbarri in the north to Busselton in the south, passing through Perth, in Western Australia. Situated on the Swan Coastal Plain, it is listed as Endangered under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. The woodlands also incorporate Perth–Gingin Shrublands and Woodlands.