The Great Famine, also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a historical social crisis which subsequently had a major impact on Irish society and history as a whole. With the most severely affected areas in the west and south of Ireland, where the Irish language was dominant, the period was contemporaneously known in Irish as an Drochshaol, literally translated as "the bad life". The worst year of the period was 1847, which became known as "Black '47". During the Great Hunger, roughly 1 million people died and more than 1 million fled the country, causing the country's population to fall by 20–25% between 1841 and 1871. Between 1845 and 1855, at least 2.1 million people left Ireland, primarily on packet ships but also on steamboats and barques—one of the greatest exoduses from a single island in history.

Ireland is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the second-largest island of the British Isles, the third-largest in Europe, and the twentieth-largest in the world.

The Popery Act of 1704 required land held by Roman Catholics to be divided equally between all a landholder's sons, both legitimate and illegitimate, on his death. This had formerly been normal under the law of gavelkind, a law abolished by the Dublin administration in 1604. Known as sub-division, this inheritance practice continued by tradition until the middle of the 19th century.

The Irish Famine of 1740–1741 in the Kingdom of Ireland, is estimated to have killed between 13% and 20% of the 1740 population of 2.4 million people, which was a proportionately greater loss than during the Great Famine of 1845–1852.

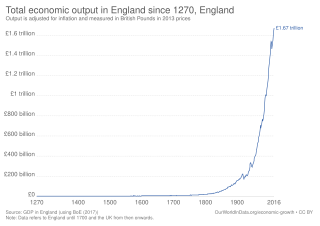

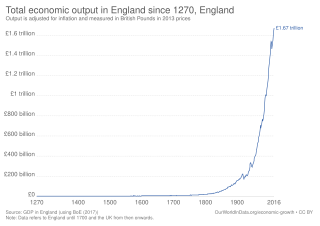

The British Agricultural Revolution, or Second Agricultural Revolution, was an unprecedented increase in agricultural production in Britain arising from increases in labour and land productivity between the mid-17th and late 19th centuries. Agricultural output grew faster than the population over the hundred-year period ending in 1770, and thereafter productivity remained among the highest in the world. This increase in the food supply contributed to the rapid growth of population in England and Wales, from 5.5 million in 1700 to over 9 million by 1801, though domestic production gave way increasingly to food imports in the 19th century as the population more than tripled to over 35 million.

Ireland was part of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1922. For almost all of this period, the island was governed by the UK Parliament in London through its Dublin Castle administration in Ireland. Ireland underwent considerable difficulties in the 19th century, especially the Great Famine of the 1840s which started a population decline that continued for almost a century. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a vigorous campaign for Irish Home Rule. While legislation enabling Irish Home Rule was eventually passed, militant and armed opposition from Irish unionists, particularly in Ulster, opposed it. Proclamation was shelved for the duration following the outbreak of World War I. By 1918, however, moderate Irish nationalism had been eclipsed by militant republican separatism. In 1919, war broke out between republican separatists and British Government forces. Subsequent negotiations between Sinn Féin, the major Irish party, and the UK government led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which resulted in five-sixths of the island seceding from the United Kingdom, becoming the Irish Free State, with only the six northeastern counties remaining within the United Kingdom.

The economic history of the Republic of Ireland effectively began in 1922, when the then Irish Free State won independence from the United Kingdom. The state was plagued by poverty and emigration until the 1960s when an upturn led to the reversal of long term population decline. However, global and domestic factors combined in the 70s and 80s to return the country to poor economic performance and emigration. The 1990s, however saw the beginning of unprecedented economic success, in a phenomenon known as the "Celtic Tiger", which continued until the 2008 global financial crisis, specifically the post-2008 Irish economic downturn. It also led to Ireland becoming the most indebted state in the European Union. As of 2015, the Republic has returned to growth, and was the fastest growing economy for that year. Since August 2017, Irish unemployment has been at a 9-year low of 6.1%. [outdated]

India was one of the largest economies in the world, for about two and a half millennia starting around the end of 1st millennium BC and ending around the beginning of British rule in India.

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of taxa. At least eleven separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin. The development of agriculture about 12,000 years ago changed the way humans lived. They switched from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to permanent settlements and farming.

The history of Ireland from 1691–1800 was marked by the dominance of the Protestant Ascendancy. These were Anglo-Irish families of the Anglican Church of Ireland, whose English ancestors had settled Ireland in the wake of its conquest by England and colonisation in the Plantations of Ireland, and had taken control of most of the land. Many were absentee landlords based in England, but others lived full-time in Ireland and increasingly identified as Irish.. During this time, Ireland was nominally an autonomous Kingdom with its own Parliament; in actuality it was a client state controlled by the King of Great Britain and supervised by his cabinet in London. The great majority of its population, Roman Catholics, were excluded from power and land ownership under the penal laws. The second-largest group, the Presbyterians in Ulster, owned land and businesses but could not vote and had no political power. The period begins with the defeat of the Catholic Jacobites in the Williamite War in Ireland in 1691 and ends with the Acts of Union 1800, which formally annexed Ireland in a United Kingdom from 1 January 1801 and dissolved the Irish Parliament.

The economy of Northern Ireland is the smallest of the four constituents of the United Kingdom and the smaller of the two jurisdictions on the island of Ireland. At the time of the Partition of Ireland in 1922, and for a period afterwards, Northern Ireland had a predominantly industrial economy, most notably in shipbuilding, rope manufacture and textiles, but most heavy industry has since been replaced by services. Northern Ireland's economy has strong links to the economies of the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain.

The economy of Belfast, Northern Ireland was initially built on trade through Belfast Harbour. Later, industry contributed to its growth, particularly shipbuilding and linen. At the beginning of the 20th century Belfast was both the largest producer of linen in the world and also boasted the world's largest shipyard. Civil unrest impacted the city's industry for many years, but with the republican and loyalist ceasefires of the mid-1990s, Good Friday Agreement and the St Andrews Agreement in 2006, the city's economy has seen some resurgence once again.

The economic history of Scotland charts economic development in the history of Scotland from earliest times, through seven centuries as an independent state and following Union with England, three centuries as a country of the United Kingdom. Before 1700 Scotland was a poor rural area, with few natural resources or advantages, remotely located on the periphery of the European world. Outward migration to England, and to North America, was heavy from 1700 well into the 20th century. After 1800 the economy took off, and industrialized rapidly, with textile, coal, iron, railroads, and most famously shipbuilding and banking. Glasgow was the centre of the Scottish economy. After the end of the First World War in 1918, Scotland went into a steady economic decline, shedding thousands of high-paying engineering jobs, and having very high rates of unemployment especially in the 1930s. Wartime demand in the Second World War temporarily reversed the decline, but conditions were difficult in the 1950s and 1960s. The discovery of North Sea oil in the 1970s brought new wealth, and a new cycle of boom and bust, even as the old industrial base had decayed.

This article covers the Economic history of Europe from about 1000 AD to the present. For the context, see History of Europe.

The first evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to around 33,000 years ago, with further findings dating the presence of homo sapiens to around 10,500 to 7,000 BC. The receding of the ice after the Younger Dryas cold phase of the Quaternary around 9700 BC, heralds the beginning of Prehistoric Ireland, which includes the archaeological periods known as the Mesolithic, the Neolithic from about 4000 BC and the Copper Age beginning around 2500 BC with the arrival of the Beaker Culture. The Irish Bronze Age proper begins around 2000 BC and ends with the arrival of the Iron Age of the Celtic Hallstatt culture, beginning about 600 BC. The subsequent La Tène culture brought new styles and practices by 300 BC.

The post-Napoleonic Depression was an economic depression in Europe and the United States after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

The economic history of the United Kingdom relates the economic development in the British state from the absorption of Wales into the Kingdom of England after 1535 to the modern United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland of the early 21st century.

The potato was the first domesticated vegetable in the region of modern-day southern Peru and extreme northwestern Bolivia between 8000 and 5000 BCE. Cultivation of potatoes in South America may go back 10,000 years, but tubers do not preserve well in the archaeological record, making identification difficult. The earliest archaeologically verified potato tuber remains have been found at the coastal site of Ancón, dating to 2500 BC. Aside from actual remains, the potato is also found in the Peruvian archaeological record as a design influence of ceramic pottery, often in the shape of vessels. The potato has since spread around the world and has become a staple crop in most countries.

The economy of Scotland in the early modern era encompasses all economic activity in Scotland between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth. The period roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

Agriculture in Ireland began during the neolithic era, when inhabitants of the isle began to practice animal husbandry and farming grains. Principal crops grown during the neolithic era included barley and wheat.