An electromagnetic field is a physical field, mathematical functions of position and time, representing the influences on and due to electric charges. The field at any point in space and time can be regarded as a combination of an electric field and a magnetic field. Because of the interrelationship between the fields, a disturbance in the electric field can create a disturbance in the magnetic field which in turn affects the electric field, leading to an oscillation that propagates through space, known as an electromagnetic wave.

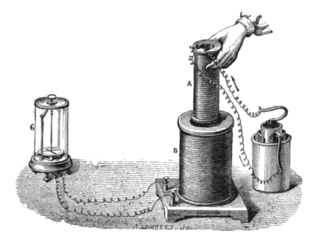

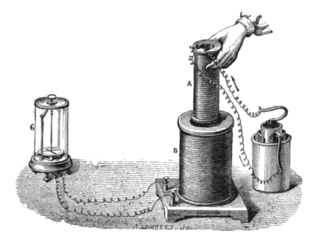

An inductor, also called a coil, choke, or reactor, is a passive two-terminal electrical component that stores energy in a magnetic field when electric current flows through it. An inductor typically consists of an insulated wire wound into a coil.

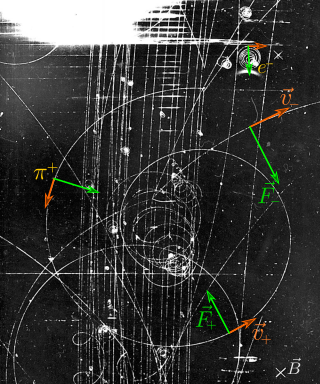

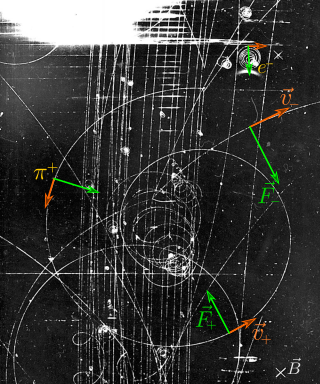

In physics, specifically in electromagnetism, the Lorentz force is the combination of electric and magnetic force on a point charge due to electromagnetic fields. A particle of charge q moving with a velocity v in an electric field E and a magnetic field B experiences a force of

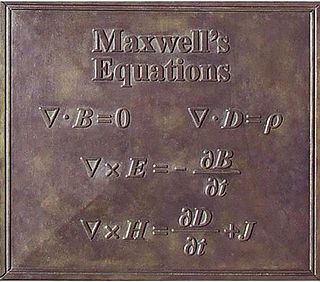

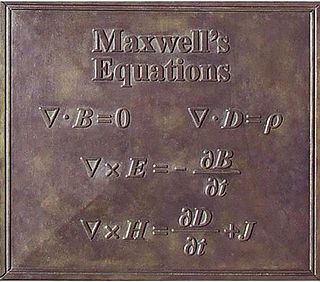

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, electric and magnetic circuits. The equations provide a mathematical model for electric, optical, and radio technologies, such as power generation, electric motors, wireless communication, lenses, radar, etc. They describe how electric and magnetic fields are generated by charges, currents, and changes of the fields. The equations are named after the physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell, who, in 1861 and 1862, published an early form of the equations that included the Lorentz force law. Maxwell first used the equations to propose that light is an electromagnetic phenomenon. The modern form of the equations in their most common formulation is credited to Oliver Heaviside.

A magnetic field is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the magnetic field. A permanent magnet's magnetic field pulls on ferromagnetic materials such as iron, and attracts or repels other magnets. In addition, a nonuniform magnetic field exerts minuscule forces on "nonmagnetic" materials by three other magnetic effects: paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and antiferromagnetism, although these forces are usually so small they can only be detected by laboratory equipment. Magnetic fields surround magnetized materials, electric currents, and electric fields varying in time. Since both strength and direction of a magnetic field may vary with location, it is described mathematically by a function assigning a vector to each point of space, called a vector field.

In electrical engineering, two conductors are said to be inductively coupled or magnetically coupled when they are configured in a way such that change in current through one wire induces a voltage across the ends of the other wire through electromagnetic induction. A changing current through the first wire creates a changing magnetic field around it by Ampere's circuital law. The changing magnetic field induces an electromotive force (EMF) voltage in the second wire by Faraday's law of induction. The amount of inductive coupling between two conductors is measured by their mutual inductance.

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport phenomena, flux is a vector quantity, describing the magnitude and direction of the flow of a substance or property. In vector calculus flux is a scalar quantity, defined as the surface integral of the perpendicular component of a vector field over a surface.

In physics, specifically electromagnetism, the magnetic flux through a surface is the surface integral of the normal component of the magnetic field B over that surface. It is usually denoted Φ or ΦB. The SI unit of magnetic flux is the weber, and the CGS unit is the maxwell. Magnetic flux is usually measured with a fluxmeter, which contains measuring coils, and it calculates the magnetic flux from the change of voltage on the coils.

In electromagnetism and electronics, electromotive force is an energy transfer to an electric circuit per unit of electric charge, measured in volts. Devices called electrical transducers provide an emf by converting other forms of energy into electrical energy. Other electrical equipment also produce an emf, such as batteries, which convert chemical energy, and generators, which convert mechanical energy. This energy conversion is achieved by physical forces applying physical work on electric charges. However, electromotive force itself is not a physical force, and ISO/IEC standards have deprecated the term in favor of source voltage or source tension instead.

Inductance is the tendency of an electrical conductor to oppose a change in the electric current flowing through it. The electric current produces a magnetic field around the conductor. The magnetic field strength depends on the magnitude of the electric current, and follows any changes in the magnitude of the current. From Faraday's law of induction, any change in magnetic field through a circuit induces an electromotive force (EMF) (voltage) in the conductors, a process known as electromagnetic induction. This induced voltage created by the changing current has the effect of opposing the change in current. This is stated by Lenz's law, and the voltage is called back EMF.

Lenz's law states that the direction of the electric current induced in a conductor by a changing magnetic field is such that the magnetic field created by the induced current opposes changes in the initial magnetic field. It is named after physicist Heinrich Lenz, who formulated it in 1834.

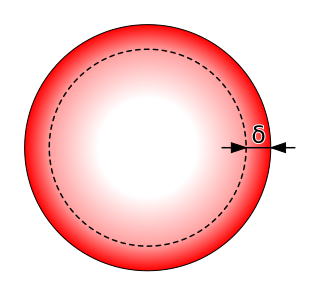

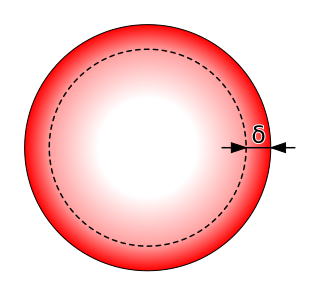

In electromagnetism, skin effect is the tendency of an alternating electric current (AC) to become distributed within a conductor such that the current density is largest near the surface of the conductor and decreases exponentially with greater depths in the conductor. It is caused by opposing eddy currents induced by the changing magnetic field resulting from the alternating current. The electric current flows mainly at the skin of the conductor, between the outer surface and a level called the skin depth. Skin depth depends on the frequency of the alternating current; as frequency increases, current flow becomes more concentrated near the surface, resulting in less skin depth. Skin effect reduces the effective cross-section of the conductor and thus increases its effective resistance. At 60 Hz in copper, skin depth is about 8.5 mm. At high frequencies, skin depth becomes much smaller.

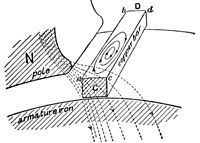

In electromagnetism, an eddy current is a loop of electric current induced within conductors by a changing magnetic field in the conductor according to Faraday's law of induction or by the relative motion of a conductor in a magnetic field. Eddy currents flow in closed loops within conductors, in planes perpendicular to the magnetic field. They can be induced within nearby stationary conductors by a time-varying magnetic field created by an AC electromagnet or transformer, for example, or by relative motion between a magnet and a nearby conductor. The magnitude of the current in a given loop is proportional to the strength of the magnetic field, the area of the loop, and the rate of change of flux, and inversely proportional to the resistivity of the material. When graphed, these circular currents within a piece of metal look vaguely like eddies or whirlpools in a liquid.

"A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field" is a paper by James Clerk Maxwell on electromagnetism, published in 1865. In the paper, Maxwell derives an electromagnetic wave equation with a velocity for light in close agreement with measurements made by experiment, and deduces that light is an electromagnetic wave.

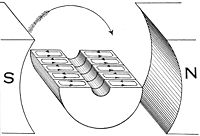

Faraday's law of induction is a law of electromagnetism predicting how a magnetic field will interact with an electric circuit to produce an electromotive force (emf). This phenomenon, known as electromagnetic induction, is the fundamental operating principle of transformers, inductors, and many types of electric motors, generators and solenoids.

A magnetic circuit is made up of one or more closed loop paths containing a magnetic flux. The flux is usually generated by permanent magnets or electromagnets and confined to the path by magnetic cores consisting of ferromagnetic materials like iron, although there may be air gaps or other materials in the path. Magnetic circuits are employed to efficiently channel magnetic fields in many devices such as electric motors, generators, transformers, relays, lifting electromagnets, SQUIDs, galvanometers, and magnetic recording heads.

The Faraday paradox or Faraday's paradox is any experiment in which Michael Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction appears to predict an incorrect result. The paradoxes fall into two classes:

In the beginning of the 19th century, many experimental and theoretical works had been accomplished in the understanding of electromagnetics. In the 1780s, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb established his law of electrostatics. In 1825, André-Marie Ampère published his Ampère's force law. Michael Faraday discovered the electromagnetic induction through his experiments and conceptually, he emphasized the lines of forces in this electromagnetic induction. In 1834, Emil Lenz solved the problem of the direction of the induction, and Franz Ernst Neumann wrote down the equation to calculate the induced force by change of magnetic flux. However, these experimental results and rules were not well organized and sometimes confusing to scientists. A comprehensive summary of the electrodynamic principles was in urgent need at that time.

The Maxwell-Lodge effect is a phenomenon of electromagnetic induction in which an electric charge, near a solenoid in which current changes slowly, feels an electromotive force (e.m.f.) even if the magnetic field is practically static inside and null outside. It can be considered a classical analogue of the quantum mechanical Aharonov–Bohm effect, where instead the field is exactly static inside and null outside.

Blondel's experiments are a series of experiments performed by physicist André Blondel in 1914 in order to determine what was the most general law of electromagnetic induction. In fact, noted Blondel, "Significant discussions have been raised repeatedly on the question of what is the most general law of induction: we should consider the electromotive force (e.m.f.) as the product of any variation of magnetic fluxsurrounding a conductor or of the fact that the conductor sweeps part of this flux?".