An architect is a person who plans, designs, and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that have human occupancy or use as their principal purpose. Etymologically, the term architect derives from the Latin architectus, which derives from the Greek, i.e., chief builder.

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. Houses use a range of different roofing systems to keep precipitation such as rain from getting into the dwelling space. Houses generally have doors or locks to secure the dwelling space and protect its inhabitants and contents from burglars or other trespassers. Most conventional modern houses in Western cultures will contain one or more bedrooms and bathrooms, a kitchen or cooking area, and a living room. A house may have a separate dining room, or the eating area may be integrated into the kitchen or another room. Some large houses in North America have a recreation room. In traditional agriculture-oriented societies, domestic animals such as chickens or larger livestock may share part of the house with humans.

Filippo Juvarra was an Italian architect, scenographer, engraver and goldsmith. He was active in a late-Baroque architecture style, working primarily in Italy, Spain, and Portugal.

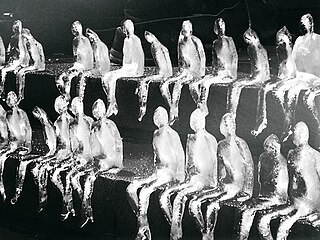

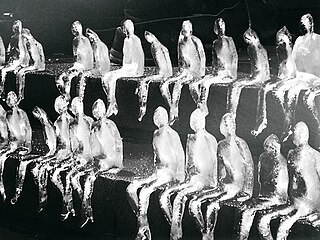

Metabolism was a post-war Japanese biomimetic architectural movement that fused ideas about architectural megastructures with those of organic biological growth. It had its first international exposure during CIAM's 1959 meeting and its ideas were tentatively tested by students from Kenzo Tange's MIT studio.

The architecture of Russia refers to the architecture of modern Russia as well as the architecture of both the original Kievan Rus', the Russian principalities, and Imperial Russia. Due to the geographical size of modern and Imperial Russia, it typically refers to architecture built in European Russia, as well as European influenced architecture in the conquered territories of the Empire.

Lebbeus Woods was an American architect and artist known for his unconventional and experimental designs. Known for his rich, yet mainly unbuilt work and its nonetheless significant impact on the architectural sphere, Lebbeus Woods and his oeuvre are considered visionary, describing a radically experimental world built on the principles of heterogeneity and multiplicity and bridging thus the gap between numerous fields including architecture, philosophy, and mathematics. Reconfiguring the architectural space in environments of crisis, whether it be natural, social, political, or financial, Woods stated: “I’m not interested in living in a fantasy world. All my work is still meant to evoke real architectural spaces. But what interests me is what the world would be like if we were free of conventional limits. Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules.”

Contemporary architecture is the architecture of the 21st century. No single style is dominant. Contemporary architects work in several different styles, from postmodernism, high-tech architecture and new references and interpretations of traditional architecture to highly conceptual forms and designs, resembling sculpture on an enormous scale. Some of these styles and approaches make use of very advanced technology and modern building materials, such as tube structures which allow construction of buildings that are taller, lighter and stronger than those in the 20th century, while others prioritize the use of natural and ecological materials like stone, wood and lime. One technology that is common to all forms of contemporary architecture is the use of new techniques of computer-aided design, which allow buildings to be designed and modeled on computers in three dimensions, and constructed with more precision and speed.

Sacral architecture is a religious architectural practice concerned with the design and construction of places of worship or sacred or intentional space, such as churches, mosques, stupas, synagogues, and temples. Many cultures devoted considerable resources to their sacred architecture and places of worship. Religious and sacred spaces are amongst the most impressive and permanent monolithic buildings created by humanity. Conversely, sacred architecture as a locale for meta-intimacy may also be non-monolithic, ephemeral and intensely private, personal and non-public.

The Palau Nacional is a building on the hill of Montjuïc in Barcelona. It was the main site of the 1929 International Exhibition. It was designed by Eugenio Cendoya and Enric Catà under the supervision of Pere Domènech i Roura. Since 1934 it has been home to the National Art Museum of Catalonia.

Spanish architecture refers to architecture in any area of what is now Spain, and by Spanish architects worldwide. The term includes buildings which were constructed within the current borders of Spain prior to its existence as a nation, when the land was called Iberia, Hispania, or was divided between several Christian and Muslim kingdoms. Spanish architecture demonstrates great historical and geographical diversity, depending on the historical period. It developed along similar lines as other architectural styles around the Mediterranean and from Central and Northern Europe, although some Spanish constructions are unique.

Architecture – the process and the product of designing and constructing buildings. Architectural works with a certain indefinable combination of design quality and external circumstances may become cultural symbols and / or be considered works of art.

The Department of Education building is a heritage-listed state government administrative building of the Edwardian Baroque architectural style located in Bridge Street in the Sydney central business district in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. The large public building was designed by Colonial Architect George McRae and built in two stages, the first completed in 1912, with John Reid and Son completing the second stage in 1938. It is also known as the Department of Education Building and the Education Building. The property was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings or other structures. The term comes from Latin architectura; from Ancient Greek ἀρχιτέκτων (arkhitéktōn) 'architect'; from ἀρχι- (arkhi-) 'chief', and τέκτων (téktōn) 'creator'. Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural symbols and as works of art. Historical civilisations are often identified with their surviving architectural achievements.

The 1929 Barcelona International Exposition (also 1929 Barcelona Universal Exposition, or Expo 1929, officially in Spanish: Exposición Internacional de Barcelona 1929 was the second World Fair to be held in Barcelona, the first one being in 1888. It took place from 20 May 1929 to 15 January 1930 in Barcelona, Spain. It was held on Montjuïc, the hill overlooking the harbor, southwest of the city center, and covered an area of 118 hectares at an estimated cost of 130 million pesetas. Twenty European nations participated in the fair, including Germany, Britain, Belgium, Denmark, France, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Romania and Switzerland. In addition, private organizations from the United States and Japan participated. Hispanic American countries as well as Brazil, Portugal and the United States were represented in the Ibero-American section in Sevilla.

The Kunsthaus Bregenz (KUB) presents temporary exhibitions of international contemporary art in Bregenz, Vorarlberg (Austria).

Antoni Gaudí i Cornet was a Catalan architect and designer from Spain, known as the greatest exponent of Catalan Modernism. Gaudí's works have a highly individualized, sui generis style. Most are located in Barcelona, including his main work, the church of the Sagrada Família.

Tadashi Kawamata is a Japanese installation artist. After first studying painting at Tokyo University of the Arts, Kawamata discovered his interest in the practice of installation. Using recuperated construction materials, like wood planks, he began building rudimentary partitions in gallery spaces and apartments to explore the perception of space.

Ephemeral art is the name given to all artistic expression conceived under a concept of transience in time, of non-permanence as a material and conservable work of art. Because of its perishable and transitory nature, ephemeral art does not leave a lasting work, or if it does – as would be the case with fashion – it is no longer representative of the moment in which it was created. In these expressions, the criterion of social taste is decisive, which is what sets the trends, for which the work of the media is essential, as well as that of art criticism.

The Palacio del Segundo Cabo was built in the last decades of the 18th century, between 1770 and 1791, as part of the urban improvement project around the Plaza de Armas.

Ephemeral architecture had a special relevance in the Spanish Baroque, as it fulfilled diverse aesthetic, political, religious and social functions. On the one hand, it was an indispensable component of support for architectural achievements, carried out in a perishable and transitory way, which allowed a cheapening of materials and a way to capture new designs and more daring and original solutions of the new Baroque style, which could not be done in conventional constructions. On the other hand, its volubility made possible the creation of a wide range of productions designed according to their diverse functionality: triumphal arches for the reception of kings and aristocratic personages, catafalques for religious ceremonies, burial mounds for funerary ceremonies and diverse scenarios for social or religious events, such as the feast of Corpus Christi or Holy Week.