The Celts or Celtic peoples were a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia, identified by their use of Celtic languages and other cultural similarities. Major Celtic groups included the Gauls; the Celtiberians and Gallaeci of Iberia; the Britons, Picts, and Gaels of Britain and Ireland; the Boii; and the Galatians. The relation between ethnicity, language and culture in the Celtic world is unclear and debated; for example over the ways in which the Iron Age people of Britain and Ireland should be called Celts. In current scholarship, 'Celt' primarily refers to 'speakers of Celtic languages' rather than to a single ethnic group.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Demeter is the Olympian goddess of the harvest and agriculture, presiding over crops, grains, food, and the fertility of the earth. Although Demeter is mostly known as a grain goddess, she also appeared as a goddess of health, birth, and marriage, and had connections to the Underworld. She is also called Deo. In Greek tradition, Demeter is the second child of the Titans Rhea and Cronus, and sister to Hestia, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus. Like her other siblings except Zeus, she was swallowed by her father as an infant and rescued by Zeus.

Poseidon is one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses. He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cities and colonies. In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, Poseidon was venerated as a chief deity at Pylos and Thebes, with the cult title "earth shaker"; in the myths of isolated Arcadia, he is related to Demeter and Persephone and was venerated as a horse, and as a god of the waters. Poseidon maintained both associations among most Greeks: he was regarded as the tamer or father of horses, who, with a strike of his trident, created springs. His Roman equivalent is Neptune.

Gaul was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of 494,000 km2 (191,000 sq mi). According to Julius Caesar, who took control of the region on behalf of the Roman Republic, Gaul was divided into three parts: Gallia Celtica, Belgica, and Aquitania.

Erecura or Aerecura was a goddess worshipped in ancient times, often thought to be Celtic in origin, mostly represented with the attributes of Proserpina and associated with the Roman underworld god Dis Pater, as on an altar from Sulzbach. She appears with Dis Pater in a statue found at Oberseebach, Switzerland, and in several magical texts from Austria, once in the company of Cerberus and once probably with Ogmios. A further inscription to her has been found near Stuttgart, Germany. Besides her chthonic symbols, she is often depicted with such attributes of fertility as the cornucopia and apple baskets. She is believed to be similar to Greek Hecate, while the two goddesses share similar names. She is depicted in a seated posture, wearing a full robe and bearing trays or baskets of fruit, in depictions from Cannstatt and Sulzbach. Miranda Green calls Aericura a "Gaulish Hecuba", while Noémie Beck characterizes her as a "land-goddess" sharing both underworld and fertility aspects with Dis Pater.

Rhiannon is a major figure in Welsh mythology, appearing in the First Branch of the Mabinogi, and again in the Third Branch. Ronald Hutton called her "one of the great female personalities in World literature", adding that "there is in fact, nobody quite like her in previous human literature". In the Mabinogi, Rhiannon is a strong-minded Otherworld woman, who chooses Pwyll, prince of Dyfed, as her consort, in preference to another man to whom she has already been betrothed. She is intelligent, politically strategic, beautiful, and famed for her wealth and generosity. With Pwyll she has a son, the hero Pryderi, who later inherits the lordship of Dyfed. She endures tragedy when her newborn child is abducted, and she is accused of infanticide. As a widow she marries Manawydan of the British royal family, and has further adventures involving enchantments.

In Gallo-Roman religion, Arduinna was the eponymous tutelary goddess of the Ardennes Forest and region, thought to be represented as a huntress riding a boar. Her cult originated in the Ardennes region of present-day Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. She was identified with the Roman goddess Diana.

Borvo or Bormo was an ancient Celtic god of healing springs worshipped in Gaul and Gallaecia. He was sometimes identified with the Graeco-Roman god Apollo, although his cult had preserved a high degree of autonomy during the Roman period.

Esus, Esos, Hesus, or Aisus was a Celtic god who was worshipped primarily in ancient Gaul and Britain. He is known from two monumental statues and a line in Lucan's Bellum civile.

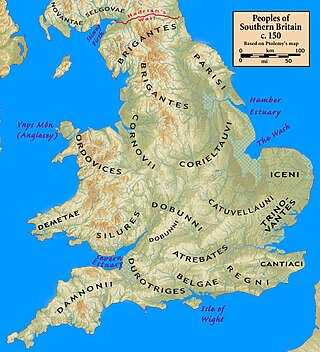

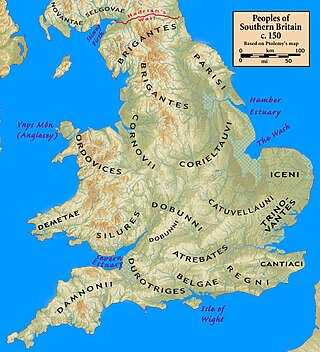

The Regni were a Celtic tribe or group of tribes living in Britain prior to the Roman Conquest, and later a civitas or canton of Roman Britain. They lived in what is now Sussex, as well as small parts of Hampshire, Surrey and Kent, with their tribal heartland at Noviomagus Reginorum.

Lusitanian mythology is the mythology of the Lusitanians, an Indo-European speaking people of western Iberia, in what was then known as Lusitania. In present times, the territory comprises the central part of Portugal and small parts of Extremadura and Salamanca.

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because there are no extant native records of their beliefs, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts, and literature from the early Christian period. Celtic paganism was one of a larger group of polytheistic Indo-European religions of Iron Age Europe.

Gallo-Roman religion is a fusion of the traditional religious practices of the Gauls, who were originally Celtic speakers, and the Roman and Hellenistic religions introduced to the region under Roman Imperial rule. It was the result of selective acculturation.

Horse worship is a spiritual practice with archaeological evidence of its existence during the Iron Age and, in some places, as far back as the Bronze Age. The horse was seen as divine, as a sacred animal associated with a particular deity, or as a totem animal impersonating the king or warrior. Horse cults and horse sacrifice were originally a feature of Eurasian nomad cultures. While horse worship has been almost exclusively associated with Indo-European culture, by the Early Middle Ages it was also adopted by Turkic peoples.

Despoina or Despoena was the epithet of a goddess worshiped by the Eleusinian Mysteries in Ancient Greece as the daughter of Demeter and Poseidon and the sister of Arion. Surviving sources refer to her exclusively under the title Despoina alongside her mother Demeter, as her real name could not be revealed to anyone except those initiated into her mysteries and was consequently lost with the extinction of the Eleusinian religion. Writing during the second century A.D., Pausanias spoke of Demeter as having two daughters; Kore being born first, before Despoina was born, with Zeus being the father of Kore and Poseidon as the father of Despoina. Pausanias made it clear that Kore is Persephone, although he did not reveal Despoina's proper name.

According to classical sources, the ancient Celts were animists. They honoured the forces of nature, saw the world as inhabited by many spirits, and saw the Divine manifesting in aspects of the natural world.

The gods and goddesses of the pre-Christian Celtic peoples are known from a variety of sources, including ancient places of worship, statues, engravings, cult objects, and place or personal names. The ancient Celts appear to have had a pantheon of deities comparable to others in Indo-European religion, each linked to aspects of life and the natural world. Epona was an exception and retained without association with any Roman deity. By a process of syncretism, after the Roman conquest of Celtic areas, most of these became associated with their Roman equivalents, and their worship continued until Christianization. Pre-Roman Celtic art produced few images of deities, and these are hard to identify, lacking inscriptions, but in the post-conquest period many more images were made, some with inscriptions naming the deity. Most of the specific information we have therefore comes from Latin writers and the archaeology of the post-conquest period. More tentatively, links can be made between ancient Celtic deities and figures in early medieval Irish and Welsh literature, although all these works were produced well after Christianization.

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context. The well-studied meld of cultures in Gaul gives historians a model against which to compare and contrast parallel developments of Romanization in other less-studied Roman provinces.

The Gauls were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period. Their homeland was known as Gaul (Gallia). They spoke Gaulish, a continental Celtic language.