Ostia Antica is an ancient Roman city and the port of Rome located at the mouth of the Tiber. It is near modern Ostia, 25 km (16 mi) southwest of Rome. Due to silting and the invasion of sand, the site now lies 3 km (2 mi) from the sea. The name Ostia derives from Latin os 'mouth'.

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples is an important Italian archaeological museum, particularly for ancient Roman remains. Its collection includes works from Greek, Roman and Renaissance times, and especially Roman artifacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Herculaneum sites. From 1816 to 1861, it was known as Real Museo Borbonico.

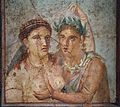

The Secret Museum or Secret Cabinet in Naples is the collection of 1st-century Roman erotic art found in Pompeii and Herculaneum, now held in separate galleries at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, the former Museo Borbonico. The term "cabinet" is used in reference to the "cabinet of curiosities" - i.e. any well-presented collection of objects to admire and study.

The Villa Poppaea is an ancient luxurious Roman seaside villa located in Torre Annunziata between Naples and Sorrento, in Southern Italy. It is also called the Villa Oplontis or Oplontis Villa A. as it was situated in the ancient Roman town of Oplontis.

The Villa of the Mysteries is a well-preserved suburban ancient Roman villa on the outskirts of Pompeii, southern Italy. It is famous for the series of exquisite frescos in Room 5, which are usually interpreted as showing the initiation of a bride into a Greco-Roman mystery cult. These are now among the best known of the relatively rare survivals of Ancient Roman painting from the 1st century BC.

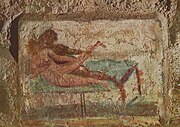

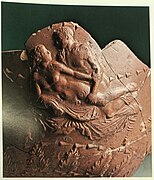

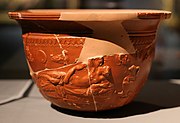

The history of erotic depictions includes paintings, sculpture, photographs, dramatic arts, music and writings that show scenes of a sexual nature throughout time. They have been created by nearly every civilization, ancient and modern. Early cultures often associated the sexual act with supernatural forces and thus their religion is intertwined with such depictions. In Asian countries such as India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Japan, Korea, and China, representations of sex and erotic art have specific spiritual meanings within native religions. The ancient Greeks and Romans produced much art and decoration of an erotic nature, much of it integrated with their religious beliefs and cultural practices.

The House of the Faun, constructed in the 2nd century BC during the Samnite period, was a grand Hellenistic palace that was framed by peristyle in Pompeii, Italy. The historical significance in this impressive estate is found in the many great pieces of art that were well preserved from the ash of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. It is one of the most luxurious aristocratic houses from the Roman Republic, and reflects this period better than most archaeological evidence found even in Rome itself.

The Lupanar is the ruined building of an ancient Roman brothel in the city of Pompeii. It is of particular interest for the erotic paintings on its walls, and is also known as the Lupanare Grande or the "Purpose-Built Brothel" in the Roman colony. Pompeii was closely associated with Venus, the ancient Roman goddess of love, sex, and fertility, and therefore a mythological figure closely tied to prostitution.

The House of the Tragic Poet is a Roman house in Pompeii, Italy dating to the 2nd century BC. The house is famous for its elaborate mosaic floors and frescoes depicting scenes from Greek mythology.

The Suburban Baths are a building in Pompeii, Italy, a town in the Italian region of Campania that was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which consequently preserved it.

A spintria is a small bronze or brass Roman token. The tokens usually depict on the obverse an image of sexual acts or symbols and a numeral in the range I - XVI on the reverse.

In the ancient Greco-Roman world, a thermopolium, from Greek θερμοπώλιον (thermopōlion), i.e. cook-shop, literally "a place where (something) hot is sold", was a commercial establishment where it was possible to purchase ready-to-eat food. In Latin literature, they are also called popinae, cauponae, hospitia or stabula, but archaeologists call them all thermopolia. They were mainly used by those who did not have their own kitchens, often inhabitants of insulae, and this sometimes led to thermopolia being scorned by the upper class.

Pompeii was an ancient city in what is now the comune of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and many surrounding villas, the city was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Stabiae was an ancient city situated near the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia and approximately 4.5 km southwest of Pompeii. Like Pompeii, and being only 16 km (9.9 mi) from Mount Vesuvius, it was largely buried by tephra ash in 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in this case at a shallower depth of up to 5 m.

In ancient Rome, a tintinnabulum was a wind chime or assemblage of bells. A tintinnabulum often took the form of a bronze ithyphallic figure or of a fascinum, a magico-religious phallus thought to ward off the evil eye and bring good fortune and prosperity.

The House of the Centenary was the house of a wealthy resident of Pompeii, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The house was discovered in 1879, and was given its modern name to mark the 18th centenary of the disaster. Built in the mid-2nd century BC, it is among the largest houses in the city, with private baths, a nymphaeum, a fish pond (piscina), and two atria. The Centenary underwent a remodeling around 15 AD, at which time the bath complex and swimming pool were added. In the last years before the eruption, several rooms had been extensively redecorated with a number of paintings.

The preservation and extensive excavations at Ostia Antica have brought to light 26 different bath complexes in the town. These range from large public baths, such as the Forum Baths, to smaller most likely private ones such as the small baths. It is unclear from the evidence if there was a fee charged or if they were free. Baths in Ostia would have served both a hygienic and a social function like in many other parts of the Roman world. Bath construction increased after an aqueduct was built for Ostia in the early Julio-Claudian Period. Many of the baths follow simple row arrangements, with one room following the next, due to the density of buildings in Ostia. Only a few, like the Forum Baths or the Baths of the Swimmers, had the space to include palestra. Archaeologist name the bathhouses from features preserved for example the inscription of Buticoso in building I, XIV, 8 lead to the name Bath of Buticosus or the mosaic of Neptune in building II, IV, 2 lead to the Baths of Neptune. The baths in Ostia follow the standard numbering convention by archaeologists, who divided the town into five regions, numbered I to V, and then identified the individual blocks and buildings as follows: (region) I, (block) I, (building) 1.

Several non-native societies had an influence on Ancient Pompeian culture. Historians’ interpretation of artefacts, preserved by the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79, identify that such foreign influences came largely from Greek and Hellenistic cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean, including Egypt. Greek influences were transmitted to Pompeii via the Greek colonies in Magna Graecia, which were formed in the 8th century BC. Hellenistic influences originated from Roman commerce, and later conquest of Egypt from the 2nd century BC.

The House of the Prince of Naples is a Roman domus (townhouse) located in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii near Naples, Italy. The structure is so named because the Prince and Princess of Naples attended a ceremonial excavation of selected rooms there in 1898.

The House of the Greek Epigrams is a Roman residence in the ancient town of Pompeii that was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. It is named after wall paintings with inscriptions from Greek epigrams in a small room (y) next to the peristyle.