An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word derives from the Greek ἐπίγραμμα. This literary device has been practiced for over two millennia.

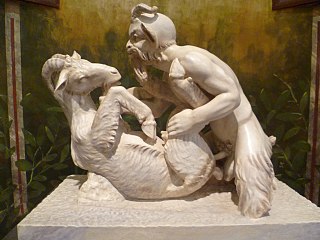

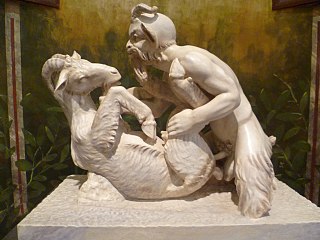

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum has been both exhibited as art and censored as pornography. The Roman cities around the bay of Naples were destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, thereby preserving their buildings and artefacts until extensive archaeological excavations began in the 18th century. These digs revealed the cities to be rich in erotic artefacts such as statues, frescoes, and household items decorated with sexual themes. The ubiquity of such imagery and items indicates that the treatment of sexuality in ancient Rome was more relaxed than in current Western culture. However, much of what might strike modern viewers as erotic imagery, such as oversized phalluses, could arguably be fertility imagery. Depictions of the phallus, for example, could be used in gardens to encourage the production of fertile plants. This clash of cultures led to many erotic artefacts from Pompeii being locked away from the public for nearly 200 years.

Garum is a fermented fish sauce that was used as a condiment in the cuisines of Phoenicia, ancient Greece, Rome, Carthage and later Byzantium. Liquamen is a similar preparation, and at times they were synonymous. Although garum enjoyed its greatest popularity in the Western Mediterranean and the Roman world, it was earlier used by the Greeks.

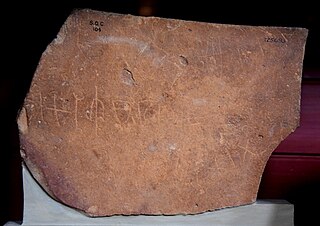

The Sator Square is a two-dimensional acrostic class of word square containing a five-word Latin palindrome. The earliest squares were found at Roman-era sites, all in ROTAS-form, with the earliest discovery at Pompeii. The earliest square with Christian-associated imagery dates from the sixth century. By the Middle Ages, Sator squares had been found across Europe, Asia Minor, and North Africa. In 2022, the Encyclopedia Britannica called it "the most familiar lettered square in the Western world".

The Secret Museum or Secret Cabinet in Naples is the collection of 1st-century Roman erotic art found in Pompeii and Herculaneum, now held in separate galleries at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, the former Museo Borbonico. The term "cabinet" is used in reference to the "cabinet of curiosities" - i.e. any well-presented collection of objects to admire and study.

A graffito, in an archaeological context, is a deliberate mark made by scratching or engraving on a large surface such as a wall. The marks may form an image or writing. The term is not usually used for the engraved decoration on small objects such as bones, which make up a large part of the Art of the Upper Paleolithic, but might be used for the engraved images, usually of animals, that are commonly found in caves, though much less well known than the cave paintings of the same period; often the two are found in the same caves. In archaeology, the term may or may not include the more common modern sense of an "unauthorized" addition to a building or monument. Sgraffito, a decorative technique of partially scratching off a top layer of plaster or some other material to reveal a differently colored material beneath, is also sometimes known as "graffito".

Homosexuality in ancient Rome often differs markedly from the contemporary West. Latin lacks words that would precisely translate "homosexual" and "heterosexual". The primary dichotomy of ancient Roman sexuality was active / dominant / masculine and passive / submissive / feminine. Roman society was patriarchal, and the freeborn male citizen possessed political liberty (libertas) and the right to rule both himself and his household (familia). "Virtue" (virtus) was seen as an active quality through which a man (vir) defined himself. The conquest mentality and "cult of virility" shaped same-sex relations. Roman men were free to enjoy sex with other males without a perceived loss of masculinity or social status, as long as they took the dominant or penetrative role. Acceptable male partners were slaves and former slaves, prostitutes, and entertainers, whose lifestyle placed them in the nebulous social realm of infamia, excluded from the normal protections accorded to a citizen even if they were technically free. Freeborn male minors were off limits at certain periods in Rome, though professional prostitutes and entertainers might remain sexually available well into adulthood.

Pompeii and Herculaneum were once thriving towns, 2,000 years ago, in the Bay of Naples. Both cities have rich histories influenced by Greeks, Oscans, Etruscans, Samnites and finally the Romans. They are most renowned for their destruction: both were buried in the AD 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius. For over 1,500 years, these cities were left in remarkable states of preservation underneath volcanic ash, mud and rubble. The eruption obliterated the towns but in doing so, was the cause of their longevity and survival over the centuries.

The House of the Faun, constructed in the 2nd century BC during the Samnite period, was a grand Hellenistic palace that was framed by peristyle in Pompeii, Italy. The historical significance in this impressive estate is found in the many great pieces of art that were well preserved from the ash of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. It is one of the most luxurious aristocratic houses from the Roman Republic, and reflects this period better than most archaeological evidence found even in Rome itself.

Safaitic is a variety of the South Semitic scripts used by the Arabs in southern Syria and northern Jordan in Ḥarrah region, to carve rock inscriptions in various dialects of Old Arabic and Ancient North Arabian. The Safaitic script is a member of the Ancient North Arabian (ANA) sub-grouping of the South Semitic script family, the genetic unity of which has yet to be demonstrated.

A fullo was a Roman fuller or laundry worker, known from many inscriptions from Italy and the western half of the Roman Empire and references in Latin literature, e.g. by Plautus, Martialis and Pliny the Elder. A fullo worked in a fullery or fullonica. There is also evidence that fullones dealt with cloth straight from the loom, though this has been doubted by some modern scholars. In some large farms, fulleries were built where slaves were used to clean the cloth. In several Roman cities, the workshops of fullones, have been found. The most important examples are in Ostia and Pompeii, but fullonicae also have been found in Delos, Florence, Fréjus and near Forlì: in the Archaeological Museum of Forlì, there is an ancient relief with a fullery view. While the small workshops at Delos go back to the 1st century BC, those in Pompeii date from the 1st century AD and the establishments in Ostia and Florence were built during the reign of the Emperors Trajan and Hadrian.

Eumachia was a Roman business entrepreneur and priestess. She served as the public priestess of Venus Pompeiana in Pompeii as well as the matron of the Fullers guild. She is known primarily from inscriptions on a large public building which she financed and dedicated to Pietas and Concordia Augusta.

The Lupanar is the ruined building of an ancient Roman brothel in the city of Pompeii. It is of particular interest for the erotic paintings on its walls, and is also known as the Lupanare Grande or the "Purpose-Built Brothel" in the Roman colony. Pompeii was closely associated with Venus, the ancient Roman goddess of love, sex, and fertility, and therefore a mythological figure closely tied to prostitution.

The tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the baker is one of the largest and best-preserved freedman funerary monuments in Rome. Its sculpted frieze is a classic example of the "plebeian style" in Roman sculpture. Eurysaces built the tomb for himself and perhaps also his wife Atistia around the end of the Republic. Located in a prominent position just outside today's Porta Maggiore, the tomb was transformed by its incorporation into the Aurelian Wall; a tower subsequently erected by Honorius covered the tomb, the remains of which were exposed upon its removal by Gregory XVI in 1838. What is particularly significant about this extravagant tomb is that it was built by a freedman, a former slave.

In the ancient Greco-Roman world, a thermopolium, from Greek θερμοπώλιον (thermopōlion), i.e. cook-shop, literally "a place where (something) hot is sold", was a commercial establishment where it was possible to purchase ready-to-eat food. In Latin literature they are also called popinae, cauponae, hospitia or stabula, but archaeologists call them all thermopolia. They were mainly used by those who did not have their own kitchens, often inhabitants of insulae, and this sometimes led to thermopolia being scorned by the upper class.

Pompeii was an ancient city located in what is now the comune of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area, was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

The Vatican Necropolis lies under the Vatican City, at depths varying between 5–12 metres below Saint Peter's Basilica. The Vatican sponsored archaeological excavations under Saint Peter's in the years 1940–1949 which revealed parts of a necropolis dating to Imperial times. The work was undertaken at the request of Pope Pius XI who wished to be buried as close as possible to Peter the Apostle. It is also home to the Tomb of the Julii, which has been dated to the third or fourth century. The necropolis was not originally one of the Catacombs of Rome, but an open-air cemetery with tombs and mausolea.

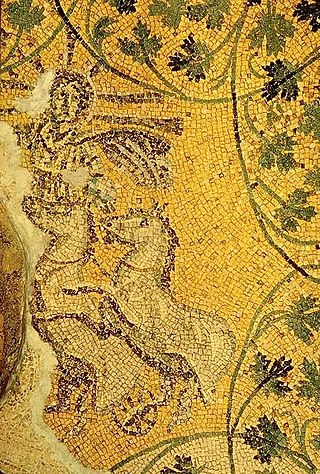

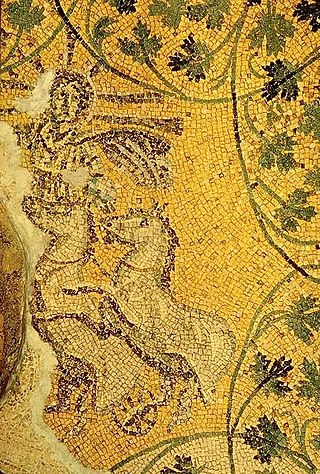

A Roman mosaic is a mosaic made during the Roman period, throughout the Roman Republic and later Empire. Mosaics were used in a variety of private and public buildings, on both floors and walls, though they competed with cheaper frescos for the latter. They were highly influenced by earlier and contemporary Hellenistic Greek mosaics, and often included famous figures from history and mythology, such as Alexander the Great in the Alexander Mosaic.

Jennifer A. Baird.jpg Jennifer Baird, is a British archaeologist and academic. She is Professor in Archaeology at Birkbeck, University of London. Her research focuses on the archaeology of Rome's eastern provinces, particularly the site of Dura-Europos.

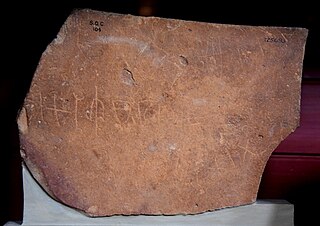

CIL 4.5296 is a poem found graffitied on the wall of a hallway in Pompeii. Discovered in 1888, it is one of the longest and most elaborate surviving graffiti texts from the town, and may be the only known love poem from one woman to another from the Latin world. The poem is nine verses long, breaking off in the middle of the ninth verse; a single line in a different hand is written underneath. It is in the collection of the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.