Pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it, it has exerted a disproportionately large influence on our understanding of Greek society. The shards of pots discarded or buried in the 1st millennium BC are still the best guide available to understand the customary life and mind of the ancient Greeks. There were several vessels produced locally for everyday and kitchen use, yet finer pottery from regions such as Attica was imported by other civilizations throughout the Mediterranean, such as the Etruscans in Italy. There were a multitude of specific regional varieties, such as the South Italian ancient Greek pottery.

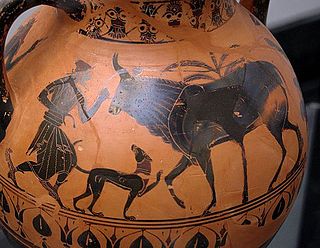

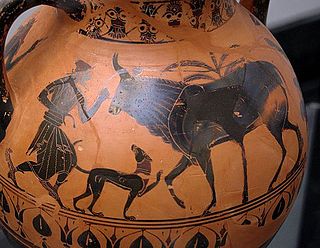

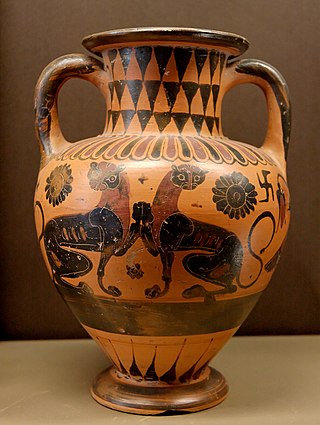

Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic, is one of the styles of painting on antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE, although there are specimens dating as late as the 2nd century BCE. Stylistically it can be distinguished from the preceding orientalizing period and the subsequent red-figure pottery style.

Exekias was an ancient Greek vase painter and potter who was active in Athens between roughly 545 BC and 530 BC. Exekias worked mainly in the black-figure technique, which involved the painting of scenes using a clay slip that fired to black, with details created through incision. Exekias is regarded by art historians as an artistic visionary whose masterful use of incision and psychologically sensitive compositions mark him as one of the greatest of all Attic vase painters. The Andokides painter and the Lysippides Painter are thought to have been students of Exekias.

Red-figure vase painting is one of the most important styles of figural Greek vase painting.

The Kleophrades Painter is the name given to the anonymous red-figure Athenian vase painter, who was active from approximately 510–470 BC and whose work, considered amongst the finest of the red-figure style, is identified by its stylistic traits.

Caere is the Latin name given by the Romans to one of the larger cities of southern Etruria, the modern Cerveteri, approximately 50–60 kilometres north-northwest of Rome. To the Etruscans it was known as Cisra, to the Greeks as Agylla and to the Phoenicians as 𐤊𐤉𐤔𐤓𐤉𐤀.

Euphronios was an ancient Greek vase painter and potter, active in Athens in the late 6th and early 5th centuries BC. As part of the so-called "Pioneer Group,", Euphronios was one of the most important artists of the red-figure technique. His works place him at the transition from Late Archaic to Early Classical art, and he is one of the first known artists in history to have signed his work.

Vulci or Volci was a rich Etruscan city in what is now northern Lazio, central Italy.

Nikosthenes was a potter of Greek black- and red-figure pottery in the time window 550–510 BC. He signed as the potter on over 120 black-figure vases, but only nine red-figure. Most of his vases were painted by someone else, called Painter N. Beazley considers the painting "slovenly and dissolute;" that is, not of high quality. In addition, he is thought to have worked with the painters Anakles, Oltos, Lydos and Epiktetos. Six's technique is believed to have been invented in Nikosthenes' workshop, possibly by Nikosthenes himself, around 530 BC. He is considered transitional between black-figure and red-figure pottery.

Bucchero is a class of ceramics produced in central Italy by the region's pre-Roman Etruscan population. This Italian word is derived from the Latin poculum, a drinking-vessel, perhaps through the Spanish búcaro, or the Portuguese púcaro.

South Italian is a designation for ancient Greek pottery fabricated in Magna Graecia largely during the 4th century BC. The fact that Greek Southern Italy produced its own red-figure pottery as early as the end of the 5th century BC was first established by Adolf Furtwaengler in 1893. Prior to that this pottery had been first designated as "Etruscan" and then as "Attic." Archaeological proof that this pottery was actually being produced in South Italy first came in 1973 when a workshop and kilns with misfirings and broken wares was first excavated at Metaponto, proving that the Amykos Painter was located there rather than in Athens.

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta, wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.

A Nikosthenic amphora is a type of Attic vase invented in the late 6th century BC by the potter Nikosthenes, aimed specifically for export to Etruria. Inspired by Etruscan Bucchero types, it is the characteristic product of the Nikosthenes-Pamphaios workshop.

Laconian vase painting is a regional style of Greek vase painting, produced in Laconia, the region of Sparta, primarily in the 6th century BC.

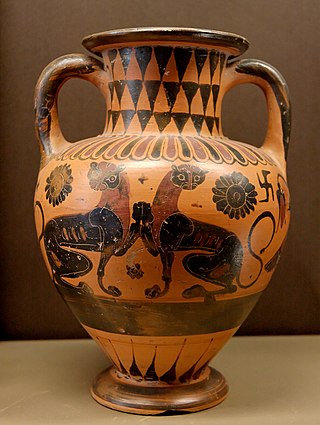

The Northampton Group was a stylistic group of ancient Greek amphorae in the black-figure style.

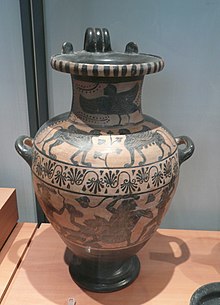

A Caeretan hydria is a type of ancient Greek painted vase, belonging to the black-figure style.

The Pontic Group is a sub-style of Etruscan black-figure vase painting.

Chalcidian pottery is an important style of Western Greek black-figure vase painting.

Pseudo-Chalcidian vase painting is an important style of black-figure Greek vase painting, dating to the 6th century BC.

Etruscan sculpture was one of the most important artistic expressions of the Etruscan people, who inhabited the regions of Northern Italy and Central Italy between about the 9th century BC and the 1st century BC. Etruscan art was largely a derivation of Greek art, although developed with many characteristics of its own. Given the almost total lack of Etruscan written documents, a problem compounded by the paucity of information on their language—still largely undeciphered—it is in their art that the keys to the reconstruction of their history are to be found, although Greek and Roman chronicles are also of great help. Like its culture in general, Etruscan sculpture has many obscure aspects for scholars, being the subject of controversy and forcing them to propose their interpretations always tentatively, but the consensus is that it was part of the most important and original legacy of Italian art and even contributed significantly to the initial formation of the artistic traditions of ancient Rome. The view of Etruscan sculpture as a homogeneous whole is erroneous, there being important variations, both regional and temporal.