Related Research Articles

Floris and Blancheflour is the name of a popular romantic story that was told in the Middle Ages in many different vernacular languages and versions. It first appears in Europe around 1160 in "aristocratic" French. Roughly between the period 1200 and 1350 it was one of the most popular of all the romantic plots.

Oscar Ivar Levertin was a Swedish poet, critic and literary historian. Levertin was a dominant voice of the Swedish cultural scene from 1897, when he started writing influential high-profile essays and reviews in the daily paper Svenska Dagbladet.

Konungs skuggsjá is a Norwegian didactic text in Old Norse from around 1250, an example of speculum literature that deals with politics and morality. It was originally intended for the education of King Magnus Lagabøte, the son of King Håkon Håkonsson, and it has the form of a dialogue between father and son. The son asks, and is advised by his father about practical and moral matters, concerning trade, the hird, chivalric behavior, strategy and tactics. Parts of Konungs skuggsjá deals with the relationship between church and state.

Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar or Hákonar saga gamla is an Old Norse Kings' Saga, telling the story of the life and reign of King Haakon Haakonarson of Norway.

Early Swedish literature designates Swedish literature written between approximately 1200–1500 AD.

The Eric Chronicle is the oldest surviving Swedish chronicle. It was written by an unknown author between about 1320 and 1335.

Euphemia of Rügen was Queen of Norway as the spouse of Håkon V of Norway. She is famous in history as a literary figure, and known for commissioning translations of romances.

Flóamanna saga, also known as Þorgils saga Ørrabeinsstjúps is one of the sagas of Icelanders. The saga has been especially noted for the realistic depiction of the main character's journey to Greenland, which may reflect the author's own experience of such a journey, or an informant's.

The Karlamagnús saga, Karlamagnussaga or Karlamagnus-saga was a late-thirteenth-century Norse prose compilation and adaptation, made for Haakon V of Norway, of the Old French chansons de geste of the Matter of France dealing with Charlemagne and his paladins. In some cases, the Karlamagnús saga remains the only source for otherwise-lost Old French epics.

Hertig Fredrik av Normandie is an anonymous, 3,310-line Swedish translation of a lost German romance, which according to Hertig Fredrik was itself translated from French at the behest of the Emperor Otto. By its own declaration, the Swedish translation was made in 1308. It is one of the three Eufemiavisorna, Swedish translations of originally French romances composed at the behest of Queen Euphemia of Rügen (1270–1312). It was subsequently also translated into Danish.

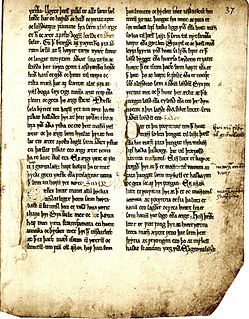

Uppsala University Library, De la Gardie, 4-7, a thirteenth-century Norwegian manuscript, is 'our oldest and most important source of so-called "courtly literature" in Old Norse translation'. It is now fragmentary; four leaves, once part of the last gathering, now survive separately as AM 666 b, 4° in the Arnamagnæan Collection, Copenhagen.

Maríu saga is an Old Norse-Icelandic biography of the Virgin Mary. Because of the wide range of sources used by its compiler and the way theological commentary has been interspersed with biography, the work is considered "unique within the continental medieval tradition on Mary's life."

Jarlmanns saga ok Hermanns is a medieval Icelandic romance saga. The saga contains the first written evidence for the Icelandic circle dance form known as hringbrot, which is also the first Icelandic attestation of elves dancing.

Konráðs saga keisarasonar is a medieval Icelandic romance saga. In the assessment of its editor Otto J. Zitzelsberger, it is 'a fine specimen of an early indigenous riddarasaga that combines elements from native tradition with newer and more fashionable ones from the Continent'. He dates it to the early fourteenth century. Although seen as highly formulaic by Jürg Glauser, Heizmann and Péza have argued that the saga provides a sophisticated exploration of identity.

Den vises sten is a fourteenth-century Swedish poem about the Philosopher's Stone.

Möttuls saga or Skikkju saga is an Old Norse translation of Le lai du cort mantel, a French fabliau dating to the beginning of the 13th century. The saga tells the story of a chastity-testing cloak brought to the court of King Arthur. It was translated, along with other chivalric sagas, under the patronage of Haakon IV of Norway. Its risqué content suggests that it was translated by clerks rather than in a religious context. Möttuls saga formed the basis for a later set of Icelandic rímur called Skikkjurímur.

Partalopa saga is a medieval Icelandic romance saga deriving from the medieval French Partenopeus de Blois.

Bevers saga or Bevis saga is an Old Norse chivalric saga, translated from a now lost version of the Anglo-Norman poem Boeve de Haumtone. Kalinke summarises the saga as follows:

"The work is a medieval soap opera that commences with the murder of Bevers's father, instigated by Bevers's mother, and carried out by a rival wooer who in turn is killed by Bevers. The ensuing plot includes enslavement, imprisonment, abductions, separations, childbirth, heathen-Christian military and other encounters - Bevers marries a Muslim princess - and mass conversions."

Erex saga is an Old Norse-Icelandic prose translation of Chrétien de Troyes' Old French romance Erec et Enide. It was likely written for the court of king Hákon Hákonarson of Norway, along with the adaptations of Chrétien de Troyes' Yvain and Perceval. The saga is preserved completely only in 17th century manuscripts.

Carl Ivar Ståhle was a Swedish linguist, toponymist, and member of the Swedish Academy.

References

- ↑ Gösta Holm, 'Eufemiavisorna', in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Phillip Pulsiano (New York: Garland, 1993), pp. 172-73.

- ↑ Gösta Holm, 'Eufemiavisorna', in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Phillip Pulsiano (New York: Garland, 1993), pp. 171-73.

- ↑ Gösta Holm, 'Eufemiavisorna', in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Phillip Pulsiano (New York: Garland, 1993), pp. 171-73.

- ↑ Gösta Holm, 'Eufemiavisorna', in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Phillip Pulsiano (New York: Garland, 1993), pp. 171-73.

- ↑ Gösta Holm, 'Eufemiavisorna', in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Phillip Pulsiano (New York: Garland, 1993), pp. 171-73.

- ↑ Marianne E. Kalinke and P. M. Mitchell, Bibliography of Old Norse–Icelandic Romances, Islandica, 44 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985).

- ↑ [https://tekstnet.dk/ivan-loeveridder/about#Eufemiaviserne Ivan Løveridder. Litteraturhistorisk baggrund. Tekster fra Danmarks middelalder og renæssance 1100-1550. Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab]

- ↑ Gösta Holm, 'Eufemiavisorna', in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Phillip Pulsiano (New York: Garland, 1993), pp. 171-73.

- ↑ Gösta Holm, 'Eufemiavisorna', in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia, ed. by Phillip Pulsiano (New York: Garland, 1993), pp. 171-73.

- ↑ Ett fragment från medeltiden ur en hittills okänd textvariant av den fornsvenska Flores och Blanzeflor, ed., with facsimile, by A. Malin, Skr. utg. av Svenska Litteratursällsk. i Finland, 156:2/Studier i nordisk filol., 12:2 (Helsingfors: Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland, 1921).